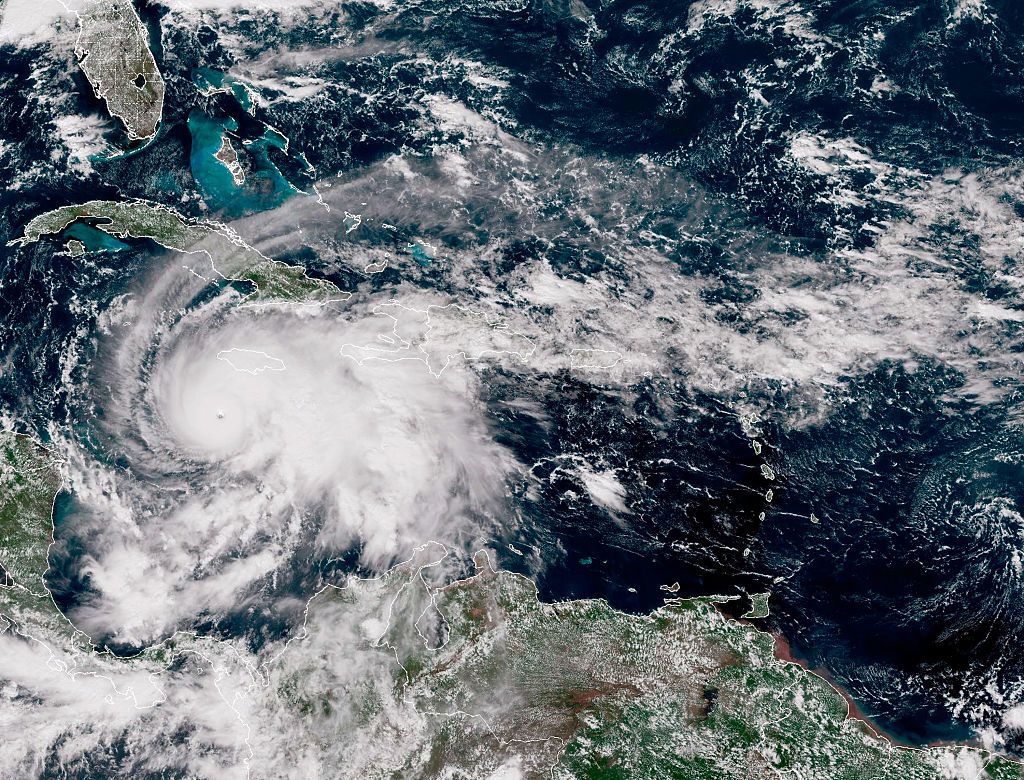

Meteorologists who have spent the past few days monitoring the rapid development of Hurricane Melissa in the Atlantic Ocean are sounding the alarm about the storm, which is set to make landfall in Jamaica today as a Category 5 hurricane. The sustained—and growing—intensity of the storm is remarkable, experts say, and has the makings of a historic hurricane.

“When I look at the cloud pattern, I will tell you as a meteorologist and professional—and a person—it is beautiful, but it is terrifying,” says Sean Sublette, a meteorologist based in Virginia. “I know what is underneath those clouds.”

There are a few ways to measure the strength of hurricanes. One is by air pressure: the lower the pressure, the stronger the storm. Early Tuesday morning, as it approached Jamaica, Melissa was measuring a minimum pressure of 901 millibars (mb)—lower than Hurricane Katrina’s peak low pressure of 902 mb and the lowest pressure ever recorded in a hurricane this late in the year, according to Colorado State University meteorologist Philip Klotzbach.

Incredibly, as of Tuesday morning, Melissa wasn’t done intensifying. At noon EDT, the National Weather Service posted an update measuring the storm’s pressure at 892 mb. If it makes landfall at this pressure, it would be tied with the catastrophic 1935 Labor Day hurricane, which hit Florida, as the most intense hurricane by pressure to make landfall.

“That record’s been in place for 90 years now,” says Brian McNoldy, a senior research associate at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric, and Earth Science. “It would be a pretty big deal if that fell.”

The pressure dropping so much as a hurricane approaches land—especially around elevated ground—is “really remarkable,” McNoldy says. “Normally it would start to feel a mountainous island, like Jamaica, and it would kind of interrupt it a little and start to weaken it. But it’s actually still intensifying right now.”

A second way of measuring hurricanes is by wind speed; Melissa has also startled meteorologists with its strength here, as well as the speed at which it intensified. Wind speeds inside Melissa measured just 70 mph on Saturday as the storm formed in the Atlantic basin, lower than the 74 mph of the mildest Category 1 storms. Just 24 hours later, however, they had jumped to 140 mph—Category 4 strength. Melissa’s winds kept intensifying through Monday and Tuesday. As of 10 am Tuesday, it had maximum sustained winds of 185 mph.

“It’s extremely rare to have a storm rapidly intensify when it’s already really intense,” says McNoldy. “You usually see rapid intensification happen when it’s a tropical storm or a Category 1, 2 hurricane. That’s when it is very common to happen. But not when it’s already at the upper end of intensity.”

Melissa started forming last week, moving from the coast of West Africa over unusually warm ocean waters. Hurricanes can’t move on their own—they travel across the ocean thanks to ocean currents, winds, and other atmospheric factors—and some, like Melissa, stall for a period of time. Usually, hurricanes that stall over water for a longer period churn up deeper, colder ocean waters, which weakens them. However, the deeper waters in the Caribbean are much warmer than the rest of the Atlantic, which supercharged the storm on its way to Jamaica.

“The ability for Melissa to lock into the deep warm water of the Caribbean and maintain such a high level of intensity for so long while moving so slow is astounding,” says Matt Lanza, a certified digital meteorologist based in Houston. “It’s not something we see very often.”

Michael Fischer, an assistant professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School, says Melissa’s strong, sustained eye—the low-pressure center of the storm—is also remarkable. Strong hurricanes, Fischer says, can often undergo a natural process called an eyewall replacement cycle, where a secondary eye will form, choking off some of the air going into the first eyewall and temporarily weakening a storm. Radar observations and data from flights near Melissa, however, show no sign of this process occurring.

“We haven’t seen any clear evidence of this kind of traditional eyewall replacement cycle,” says Fischer. “I think that’s kind of unusual for a storm of this intensity.”

Melissa is the third Category 5 storm to form in the Atlantic this season—the first time this has happened since the deadly 2005 season, which brought Hurricanes Emily, Katrina, Rita, and Wilma. Sublette says that Katrina, which weakened slightly before making landfall as a Category 3, is not the correct comparison for how this storm could hit Jamaica today. Rather, he compares the potential impact of Melissa to 1992’s Hurricane Andrew, which made landfall in Florida as a Category 5 storm with 165 mph wind speeds—still far slower than Melissa was on Tuesday morning. Andrew is one of the most catastrophic storms to hit the US, causing 65 deaths and costing more than $27 billion in damage in 1992 dollars.

Once the storm hits Jamaica, Sublette says, he worries about what will happen when it interacts with the island’s mountains. “The wind is gonna be even higher” in the mountains, he says. “The rainfall is gonna be worse. There are going to be landslides—that’s not something we had in New Orleans or Miami.”

McNoldy is careful to point out that climate change does not cause specific storms to form, but merely ups the odds of them being more intense. But there’s no doubt that ocean waters have warmed in the 20 years since Hurricane Katrina and that those warm waters helped strengthen Melissa.

“I think that the fact that the Caribbean is so warm relative to normal has played a big role here,” says Lanza. “It makes you wonder if this is going to become a new normal going forward when we get storms like this.”