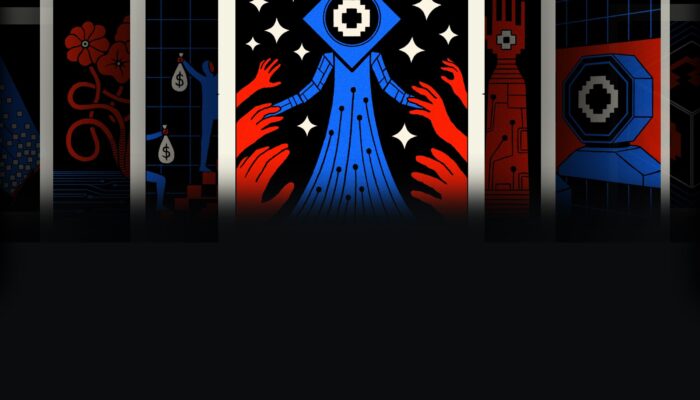

To be human is to yearn for a Sky Daddy. Something that explains the unexplainable, someone to blame. No wonder, then, that in the ZIRP-fueled 2010s, when a new gospel of creation was being spread, some people started to see technology as a kind of religion. And on the eighth day, He made a mobile app that delivered us our daily bread—that sort of thing.

Startup founders and CEOs became messianic figures. Alms-giving got a new name: effective altruism. Biohacking was ritualized, and the singularity seemed ever nearer. These would save humanity from “as Biblical a scourge as there ever was: death itself,” wrote Greg Epstein, a humanist chaplain at Harvard and MIT, in his book Tech Agnostic. All of this was as close as Silicon Valley, famously skeptical and not so secretly libertarian, would come to publicly embracing theology.

Then there was a turn: Prominent technologists began evangelizing not tech as religion but religion as religion. Earlier this year, I found myself in an expensive condo, converted from a church, in San Francisco’s Mission District, listening to a venture capitalist turned arms dealer recite parts of the Lord’s Prayer to a crowd of 200 techies. Inspired by a religious speech Peter Thiel gave at a private birthday party a few years earlier, this VC’s wife launched a group called ACTS 17 Collective—Acknowledging Christ in Technology and Society—as a means of spreading the gospel to Silicon Valley. The actual gospel, not the tidy solutionism of technology.

An entrepreneur sitting next to me that night admitted he’d long been religious. He just hadn’t felt comfortable wearing his faith on his sleeve in Silicon Valley, until now. Another attendee asked me, in casual conversation, how many kids I wanted (not with him; just in general). Be fruitful and multiply and all that. More recently, Thiel gave a series of off-the-record lectures for the ACTS 17 crowd, no doubt expounding on his belief that a young Swedish climate and antiwar activist is representative of the Antichrist.

In the weeks after the Christian right-wing activist Charlie Kirk was publicly assassinated, prominent techies began posting religious passages on X. “Forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us,” Elon Musk wrote. The venture capitalist Jason Calacanis—who has also, it should be noted, lambasted ICE for its violence against immigrants—offered a blanket apology to anyone he has wronged. “I’m always trying to get better at what I do and as a son of Christ,” he wrote on X. If the most ruthless capitalists are finding religion again, then maybe there’s hope for the rest of us. After all, religion and capitalism are both very good at creating incentives for us mere mortals.

And on top of everything, now there’s AI. What role does it play in the new religion? Anthony Levandowski, one of the cofounders of Waymo, started his (in)famous Church of AI a full decade ago—this stuff isn’t exactly new. AI, he suggested, should be worshipped as a kind of god.

So … should it?

No. No. Right? Well. Depends on who you ask, or how literal the interpretation is. Musk recently “joked” that by the time OpenAI’s copyright infringement lawsuits are all settled up, the legal system will be irrelevant, because “we’ll have Digital God. So, you can ask Digital God.” On Twitch, thousands of people are viewing a livestream of AI Jesus as I type this. Some people ask for pizza recommendations in Chicago; others ask whether they’re going to hell for masturbating. The handsome, ethereal AI Jesus pauses before saying “Lou Malnati’s” or “the concept of self-love is important” and then wrapping it all in scripture. (The pizza rec alone might be evidence enough that AI is not all-knowing.)

Even the Vatican has thoughts. We all remember when, in 2023, Pope Francis became a meme swathed in an AI-generated Balenciaga coat—such fun and games. The newly appointed Pope Leo is now warning tech leaders of the perils of an all-powerful AI. Earlier this year, the Vatican, along with the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences and Notre Dame Law, organized a gathering of clergy, academics, and policy wonks to discuss AI, calling it “another industrial revolution” that could “pose new challenges for the defense of human dignity, justice, and labor.”

To recap: If, over the past few decades, tech became the new religion, and then religion became the religion, you could say that AI is now religion operationalized—something definitive yet unexplainable, an instrument we can cast our highest hopes onto and later blame. Our new Sky Daddy.

But here’s my best case for why generative AI is not God: because it’s human. It’s built from a massive trove of human data. Here, I present to you: 10 billion humans plopping personal data into machines.

Generative AI oscillates from soulful to cold, nonsensical to brilliant, scornful to sycophantic. It’s remarkably banal; it’s stunningly weird. It proclaims it loves us (it doesn’t). It drives us fucking bananas. Is its mere existence miraculous? Sure. So is ours. Is it smarter than me? Sure, but so are a lot of humans. That doesn’t stop it from sometimes being catastrophically or hilariously wrong … just like us. Human, machine, whatever: Fallibility is our God-given right. AI is not your god. Only God knows if it ever will be.

Unless, of course, we’re living in a simulation. Then the AI might actually be God. And, in that case, which evil genius programmed the AI? Elon Musk?

Dear god.