By the time President Trump returned to office earlier this year, TikTok’s fate should have been sealed. Congress had passed, and President Biden had signed, a law requiring the app to be banned or sold by the day before Inauguration Day. But Trump announced he would effectively pause the law. Instead, he said he would “save” the app by brokering a belated sale.

Now, Trump’s attempt to make that sale has taken shape: Last week, the White House announced a plan for TikTok’s Chinese parent company, ByteDance, to license a copy of the app’s algorithm to a consortium of investors, at least some of whom have been vocal supporters of Trump’s political agenda. If the plan is finalized, TikTok’s US business will fall into the hands of powerful Trump allies at a moment of unprecedented media consolidation.

But that transition, if it happens, will challenge the culture that defined TikTok in its early days. This excerpt from my book, Every Screen On the Planet: The War Over TikTok, traces one of the company’s first and most prominent run-ins with Trump: an attempt by a group of young TikTokkers to prank the president and tank attendance at one of his campaign rallies. At the time, the stunt was largely dismissed as funny—but it also revealed how TikTok, and the people using it, could shape our politics in the years to come.

Kevin Mayer is six feet, four inches tall, with a square jaw, light eyes, and a deep voice. He’s built like an offensive tackle—a position he once played on MIT’s football team—and has the unfortunate habit of sending emails with subjects in all caps. When ByteDance founder Zhang Yiming first approached him about becoming CEO of TikTok, he had served more than 20 years as an executive at Disney, where he had risen to lead the Disney+ streaming platform. He had been a candidate to succeed the conglomerate’s legendary CEO, Bob Iger, when he stepped down in early 2020. But Mayer, who had earned the nickname “Buzz Lightyear” for the way his demeanor (and jawline) resembled the Disney Pixar character, had been passed over for the job.

Yiming approached Kevin at the beginning of the pandemic. Disney’s prospects had tanked as movie theaters shuttered. But TikTok was a rocket ship Kevin, then 58, decided to take a ride on.

“I’m not getting any younger,” he said.

In May 2020, Kevin accepted an offer to become global CEO of TikTok and chief operations officer of ByteDance. In a way, TikTok was as much like Disney+ or Netflix as it was like Facebook or Google. Obviously, user-generated content was a new and different beast for Kevin. The challenge of studying what people watched and convincing them to watch more, though, was familiar—as was the job of courting and persuading advertisers that this platform offered the best value for their money.

Kevin was bright, engaged, and good with numbers. “Every meeting was a lot of energy with Kevin,” said one executive who worked with him. He was more assertive than Alex, and he wasn’t a software engineer, but that was just as well. It meant he didn’t develop or express as many strong opinions about how the technology behind TikTok should work—a topic that Yiming already felt strongly about. He could better focus on executive decision-making, and projecting confidence and competence to TikTok’s staff and the rest of the world.

For many of ByteDance’s employees, Kevin’s hiring meant there would be an IPO. IPOs—“initial public offerings”—are the vehicle by which private companies become public, finally allowing investors and employees to sell their stock. Going public was the ultimate coming-of-age moment for a startup, and most of ByteDance’s competitors, both in the US and in China, had made a lot of money doing it.

In Silicon Valley, it was well known that IPOs minted millionaires. Engineers, marketing managers, designers, and lawyers left steady jobs to roll the career dice at startups: the company might go under, but if it sold, they might get rich. At most tech companies, including ByteDance, employees were paid partially in company stock. At private companies, that stock was like a stack of lottery tickets: potentially worthless, potentially valuable. If the company IPO’d, employees could sell the stock on the open market, and suddenly those lottery tickets would be worth hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars.

Within two months of lockdown in 2020, it was clear TikTok was a success and ByteDance was unlikely to suddenly shut its doors in the United States. But there was unease among US employees about whether its foreignness would prevent it from soaring. Working for an international company was fun for the company’s young American workforce—Chinese food in the cafeteria felt different, and so did the red envelopes filled with cash at Chinese New Year. But as President Trump raved about the “Kung Flu” and hate crimes against Asian Americans spiked, some worried: Would TikTok even be allowed to IPO? What if the IPO was in China, instead of the US? Would that change how employees could cash out?

ByteDance’s US staff trusted Buzz Lightyear with these questions. Kevin Mayer “was the deal guy,” an American executive who worked with him told me, referencing his track record of partnerships at Disney. “He was the deal guy brought in to take it public.”

That executive and others hoped Kevin would Americanize TikTok in other ways. They imagined he might pull the company’s center of gravity away from Beijing, ending the Chinese-language Lark chats, Sunday night meetings, and mass-shaming emails. US employees hoped that Pacific time would become TikTok’s governing time zone, and English its default language. In other words, they wanted to work as a “regular” tech company. And they hoped Kevin would provide ultimate clarity on the question of who was in charge.

Before Kevin Mayer even opened his new work laptop, things went haywire.

On May 25, 2020, a white Minneapolis police officer named Derek Chauvin dug his knee into the neck of a 46-year-old Black man named George Floyd, ultimately killing him. A 17-year-old bystander posted a video of the act on Facebook; it soon was viral on every platform.

The video of George Floyd’s murder was a historic moment for the internet. The witness who filmed was awarded a special citation by the Pulitzer Prize board. Platforms across the world balked at hosting graphic video of a person’s murder—but they also knew that not allowing users to share it, or suppressing the video, would be far worse.

First in Minneapolis, and then nationwide, vigils commemorated Floyd and protestors marched by the thousands, chanting Floyd’s tragic refrain: “I can’t breathe.” For many demonstrators, these gatherings were their first public outings since the pandemic began—their first time breaking isolation, taking public transit, or being in close proximity to anyone other than their families. Emotions ran extremely high. The empowering exhilaration of mass solidarity swirled with the danger of exposure to the virus, heightened by the presence of police at many marches.

At a protest in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, in late May, a progressive organizer named Abby Loisel saw a young boy standing on a rock watching protestors go by. Loisel, who described attending a protest that week as “an out of body experience,” asked the boy’s mother if she could film the moment, and captured a protester giving the boy a fist bump as they marched by. “I just thought it was really sweet,” she said. She set the video to Childish Gambino’s “This Is America,” and posted the video to TikTok later that day.

Other videos gained traction as well. Footage of burning cars and looting of stores started circulating and clashing with solidarity posts from people who had remained at home for fear of the virus. Celebrities and politicians weighed in. President Trump threatened to suppress the gatherings with the military, a striking threat that further inflamed tensions.

The For You algorithm loved every angle of the George Floyd controversy. ByteDance’s algorithm had been built to identify trends, new topics that lots of people were suddenly posting about and commenting on. The algorithm especially liked videos with new music. “This Is America” became the summer’s protest anthem. A mass protest movement had all the qualities that made content pop on the app. But George Floyd’s death was exactly the opposite of what Alex Zhu had wanted the app to be.

George Floyd was killed one week after Zhang Yiming announced Kevin Mayer’s hire at TikTok, and one week before he actually started the job. Kevin wasn’t a political figure. He was a finance guy, a shrewd dealmaker whose vision for TikTok was polished, professional entertainment—not a fraught quagmire of users’ thoughts on race and policing.

Kevin described his first days at TikTok as a moment when the platform itself went through a massive change: before then, he said, the app was “happy and joy all over.” But after Floyd’s killing, that changed. The For You algorithm had learned something new—it had met a new type of trend, one with more power than the most captivating possible teen lip-synch.

In a webinar with entertainment consultant Peter Csathy a few weeks into his tenure as CEO, Kevin acknowledged the platform’s shift. “Maybe the most important thing isn’t joy, it’s social justice. … We have the responsibility to be that platform when people want to express their anger and belief in social justice.”

Alex Zhu’s warning about leaning into politics loomed large over Kevin’s first days. But Kevin hardly had a choice in the matter. If TikTok had tried to limit discussion about the killing, it would’ve been accused of censorship and indifference to racial justice, which every other Fortune 500 company in the US was making new commitments to support. Neither Yiming nor Kevin could have insisted that TikTok stay out of politics in a moment when its own users were marching in the streets.

So on his first day at work, Kevin issued a statement aligning the platform with the protest movement:

As I begin my work at TikTok, it has never been a more important time to support Black employees, users, creators, artists, and our broader community. I am making this commitment from today, my Day 1.

Words can only go so far. I invite our community to hold us accountable for the actions we take over the coming weeks, months, and years. Black Lives Matter.

Summer 2020 is remembered for its racial justice protests and Covid quarantines, but it also produced the strangest presidential campaign in modern US history. Social distancing prevented the traditional door-knocking and rallies. So the erratic populist president, Republican Donald Trump, faced centrist liberal Democrat Joe Biden in a campaign waged almost entirely online and on television.

TikTok played a limited role in the 2020 election. The company wanted no part in electoral politics, and many politicians wanted nothing to do with TikTok. Both the Democratic and Republican National Committees advised candidates and staffers not to use the app, because of its Chinese origins, and asked staffers to delete it and suspend their accounts. A group of Republican senators introduced and passed a bill that banned it on government devices.

Kevin Mayer had inherited TikTok’s policy of refusing political ads. But he and his teams couldn’t police transactions that happened beyond its proverbial walls, so some opportunistic politicians and political strategists began offering entertainers and influencers cash to post political messages on the platform. Because TikTok didn’t restrict political messages, and couldn’t tell which ones were paid for, it couldn’t enforce its rules and take down the posts

Still, for the first half of 2020, TikTok largely avoided the limelight. Its users were overwhelmingly young—often so young they couldn’t even vote. According to one internal document, more than one-third of TikTok users in early 2020 were 14 or younger. Those who could vote were mostly still under 35 years old: a group that wasn’t particularly excited about either Trump or Biden.

Then, Trump decided to reenter the arena. The all-digital campaign had favored Biden, as it protected him from the rigors of the campaign and gaffe-prone events, while allowing his disciplined digital campaign to portray him as a seasoned, reasonable moderate. Trump, who had ridden to victory in 2016 on a campaign fueled by raucous rallies, was hurt by the virtual contest. That June, when the public began to tire of Covid restrictions, he announced the return of his rally tour. His first stop would be on June 19, at the BOK Center in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

The announcement was immediately controversial, for two reasons. The first, of course, was Covid. In its mid-2020 form, months before vaccines were available, the disease caused death and lifelong illness in many of the people it infected. Packing thousands of people into an enclosed, indoor arena violated guidance from the World Health Organization, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and nearly every other public health authority. Holding the rally itself was an act of defiance, a statement that personal freedom was more important than what Trump supporters saw as bureaucratic public health guidance.

The rally was also scheduled to occur on Juneteenth, the Black American holiday celebrating the end of slavery, at the site of a brutal act of racist terror, the 1921 massacre on Tulsa’s Black Wall Street. Trump already had a reputation for racist behavior: the federal government once sued him for discriminatory lending, he aggressively campaigned to put five wrongly accused Black and Latino teens in prison, and a former colleague described him using the N-word on the set of his TV show, The Apprentice. So when he announced the time and place of his comeback rally, some people questioned whether the plans reflected callous ignorance—or outright animus.

The Trump campaign would later announce that they were moving the rally back by a day, to June 20, but by then, the damage had been done. On June 11, the day after Trump first announced the rally, a political commentator and reality TV star named Quentin Jiles made a TikTok explaining the stakes: “Not only is this man totally insensitive to the moment, I think it’s a doubling down. Because we know where his heart is. We know he’s a racist.”

The video got just shy of 10,000 likes—pretty standard for Jiles, given his celebrity and following at the time. Under it, though, comments began to stream in from followers saying they’d reserved tickets to the rally, though they had no intent to go. “Don’t worry we got your back!” one commenter wrote. “Already rsvp’ed my free tickets. That rally will be at minimum capacity, go get your two free tickets right now!”

Then commenters started sharing the URL to Trump’s campaign website, with instructions about how to reserve tickets—and reservations poured in.

A few hours after Jiles posted his video, another TikToker chimed in. Mary Jo Laupp, a 51-year-old high school theater director in Fort Dodge, Iowa, made a follow-up video calling the rally “a slap in the face to the Black community.” She urged her small community of followers—at that point, just about a thousand people—to educate themselves about Juneteenth and the Tulsa massacre. But she didn’t stop there.

“Somebody on another TikTok post commented that [Trump] was offering two free tickets on his campaign website to go to this rally, so I went and investigated it,” Laupp spoke quickly and purposefully into the camera. “It’s two free tickets per cell phone number,” she said, “so, I recommend that all of us that want to see this 19,000 seat auditorium barely filled or completely empty go reserve tickets now, and leave him standing alone on the stage. Whadda ya say?”

Every once in a while, an internet meme reaches escape velocity and explodes into the real world—and that’s what happened in response to Mary Jo Laupp’s video. It received more than 2 million views and thousands of comments in the following days. Many of those comments said, simply, “algorithm.”

The Laupp commenters were doing something technologically new for TikTok: they were turning the app’s recommendations engine on its head—making it work for them, instead of just letting it act upon them. They knew that TikTok ran nearly entirely on revealed preferences, rather than stated ones. So they found a way to creatively state their preferences anyway, in a language the machine would understand.

To be clear: TikTok’s algorithm wasn’t responding to the word “algorithm,” as if the users were calling its name. The users just understood that under the hood, TikTok (like Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter) was essentially a big math equation, adding up the weights of a bunch of different signals to decide how much reach each post would receive. By commenting any text on the post, they could add a few points to the “comments” column, driving the total reach of the post up a little bit.

One comment in particular amassed more than 70,000 likes. The account that posted it, which said it was a 21-year-old named Yesenia, had made only one post. The comment said, “Bro get kpop stan on this.”

K-pop “stans,” for those unfamiliar, are fans of Korean pop supergroups like BTS and BLACKPINK. There are millions of them in the United States and around the world, and they are generally young, passionate, and extremely online.

In summer 2020, K-pop stans became famous for disrupting bigoted online movements by “flooding the zone” with wholesome memes. In the week before Trump announced his Tulsa rally, a group of white supremacists began posting on Twitter using the hashtag #whitelivesmatter. Within hours, use of the hashtag soared, but anyone who actually clicked on it was met with photos and videos of K-pop artists, songs, choreography. The racist posters, overwhelmed and wrong-footed, reorganized under the hashtags #whitelifematters and #whiteoutwednesday, only to quickly find those hashtags flooded with K-pop too.

The week before #whitelivesmatter, K-pop devotees had set their sights on Dallas, where the Dallas Police Department had launched an app through which citizens could upload reports of “illegal activity from the protests” following George Floyd’s death. A 16-year-old K-pop fan tweeted asking her followers to “FLOOD that shit” with footage of K-pop stars. “Make it SO HARD for them to find anything besides our faves dancing,” she wrote. The next day, the Dallas Police Department announced that its iWatch app had experienced “technical difficulties” and was down.

Just minutes after Yesenia’s call to mobilize K-pop stans, replies started streaming in. “We heard u sis we on it,” one wrote. “We here now,” quipped another. “On it” said a third, who posted the comment with the “nailcare” emoji, often used to convey sass and confidence. Anti-Trump TikTokers without K-pop ties cheered the stans on, and made their own posts tagging K-pop accounts, calling them to action, and thanking them—as several commenters put it—“for their service.”

On Friday June 12, less than 24 hours after Laupp posted her video, Trump’s campaign manager, Brad Parscale, tweeted that over 200,000 tickets had already been reserved for the rally. Later in the day, he wrote: “Correction now 300,000!” and, two days later, “Just passed 800,000 tickets. Biggest data haul and rally signup of all time by 10x.” Trump himself also tweeted: “Almost One Million people requested tickets for the Saturday Night Rally in Tulsa, Oklahoma!”

TikTokers reposted the tweet with gleeful comments: “Who requested all those seats though!?”

The ticket reservation bonanza was reminiscent of the 2021 “meme stock” Reddit campaign that led hundreds of hobbyist investors to manipulate the market for GameStop, sticking it to billionaire money managers who had sold the foundering video game retailer short. Like the GameStop surge, the Tulsa campaign was subversive—it gave everyday people (many of them too young to vote) a way to collectively express their distaste for the president in a moment of crowdsourced revolution. The hobbyist investors had organized online to defeat the investor class (if only in the short term), and the ticket reservers did the same to prank the most powerful man on earth.

The Trump campaign’s trip to Tulsa was a nightmare from the start. On the morning of the rally, eight members of the campaign staff tested positive for Covid at their hotel. Campaign leaders told the sick staffers to rent cars and drive home—and ordered the rest to stop testing, lest they identify further casualties. (This strategy widened the outbreak.)

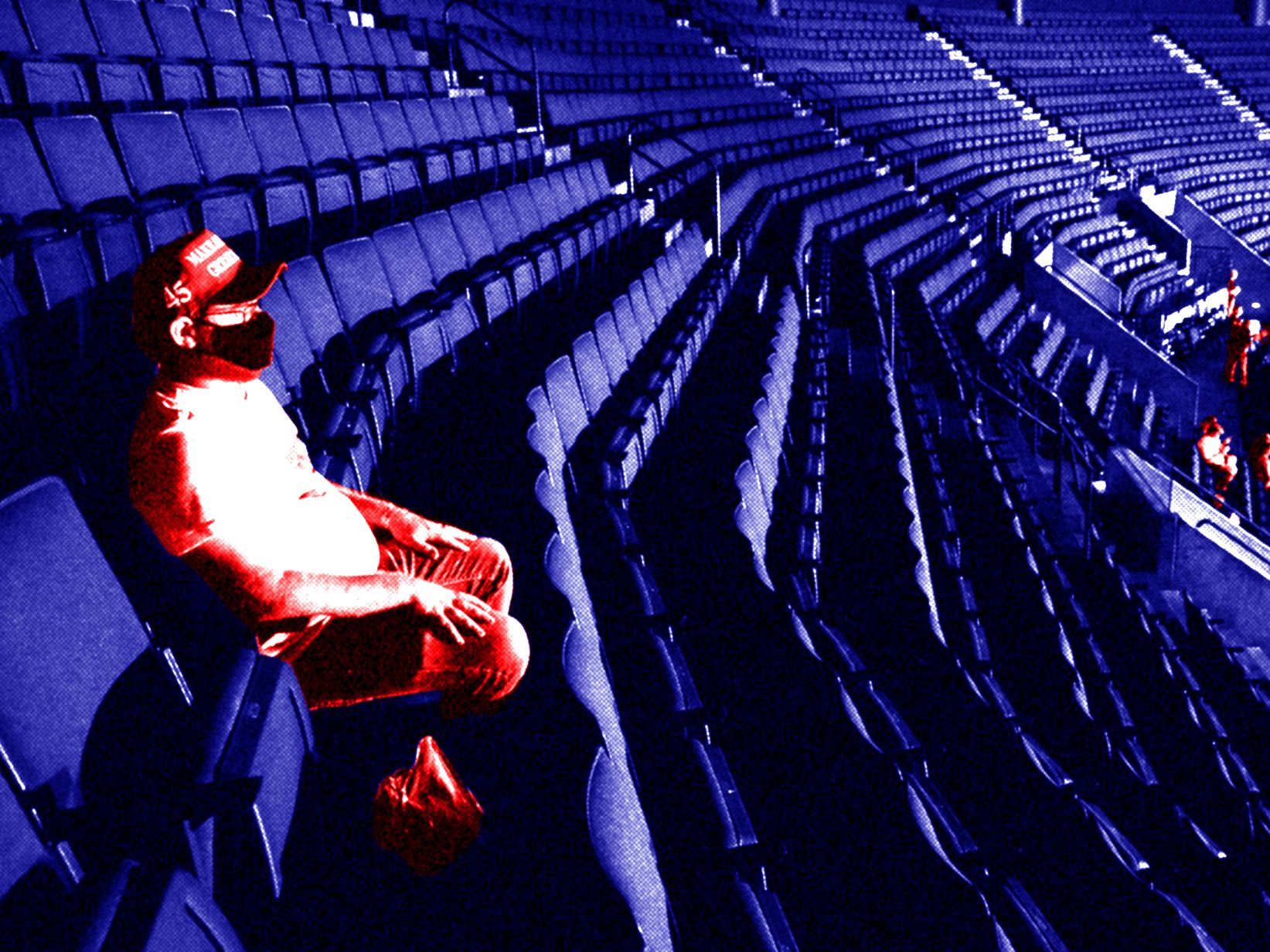

President Trump’s priority, though, was the crowd. A few hours out from the event, he called Parscale from Air Force One to ask whether the arena would be full. Parscale, who could see the parking lot, knew it wouldn’t. According to reporting from ABC News anchor Jonathan Karl, Parscale replied, “No sir. It looks like Beirut in the eighties.” As his staffers looked out into the largely empty stadium on June 20 in Tulsa, they knew just how unpleasant their evening was about to become. Parscale told his top lieutenants, “None of you should go anywhere near the president today, including me.” In the end, only about 6,000 people attended the event, in an arena that held 19,000. The optics were spectacularly bad.

Parscale would ultimately lose his job over the rally in Tulsa. It was a disaster for the Trump campaign—a sign that, after three years of their leader in office and months of a deadly pandemic that had claimed hundreds of thousands of lives, the MAGA faithful of 2016 might just have lost their zeal. But it was also TikTok’s first inside-the-Beltway moment, one that would haunt the platform for years to come.

TikTok teens almost certainly weren’t the only reason people didn’t show up to the MAGA rally in Tulsa. The city’s own public health department had opposed the rally and urged people to stay home. But for TikTok’s PR team and Kevin Mayer, now in his third week on the job, the event was a crisis. News outlets like the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal rushed to cover the platform’s newfound effects on politics. Just seven months prior, TikTok’s previous head, Alex Zhu, had told the Times that TikTok wanted to be a place of public entertainment, not the town square. Now his fears had come true: TikTok, along with Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube, had become ground zero for political activism.

For many of TikTok’s users, the moment was a hilarious triumph. A horde of mostly teenage girls had tanked the comeback rally of a grown-up bully with famously little regard for girls or women. It was the type of feel-good story Hillary Clinton supporters would call their moms to laugh about.

Steve Schmidt, a Republican political strategist and opponent of President Trump, wrote on Twitter: “The teens of America have struck a savage blow against @realDonaldTrump. All across America teens ordered tickets to this event. The fools on the campaign bragged about a million tickets. Lol.”

“Lol” was also the position of many staffers who worked for TikTok. The rally—and the prank leading up to it—wasn’t on the radar of most TikTok employees before it happened. In the grand scheme of things it wasn’t even that big a trend on the platform. Even after the fact, one former executive told me, it didn’t particularly raise alarm bells. “A lot of the staff are quite progressive,” the person said. “They thought it was pretty cool.”

The prank hadn’t violated any of TikTok’s rules. It would be crazy for TikTok to prohibit people from posting videos about ordering tickets to an event and then not attending it. There had been no spam, no misrepresentation, no inauthenticity. And because the campaign hadn’t limited the number of people who could register, it’s unlikely that the pranksters actually stopped anyone from attending the rally, either. Their sole crime had been embarrassing a guy who was unusually sensitive about his crowd size.

But it wouldn’t be too hard to imagine a more troubling use of the same tactics. In October 2020, a cybersecurity researcher named Thaddeus Grugq published a blog post characterizing BTS ARMY, one of the K-pop stan groups that facilitated the Trump troll, as a “non-traditional, non-state actor”—a designation of increasing interest to those studying platform manipulation in the wake of Russia’s 2016 election interference.

ARMY (as the BTS fan group called itself) had years of experience conducting mass engagement drives online. Grugq pointed out that because many Korean pop music awards pick their winners by online votes, fan groups had years of experience orchestrating digital “ballot stuffing” for their band of choice. He also described a number of “antiband” tactics—efforts undertaken by one fandom to sabotage another.

“One tactic used by kpop fandoms against rival bands is to book tickets for shows and then cancel at the last minute,” he wrote. “The intention being to deny access to the real fans, to create a false impression of market interest, and/or to deny the band an audience thus impacting their concert revenue and embarrassing them.” Donald Trump, whose rallies resembled rock concerts, had pretty clearly been the victim of an “antiband” attack.

“What is the cyber force ARMY currently capable of?” Grugq asked. “Pretty much anything you can do with a million people coordinated online.”

Excerpt adapted from Every Screen on the Planet: The War Over TikTok by Emily Baker-White. Published by arrangement with W.W. Norton. Copyright © 2025 Emily Baker-White.