Google wants to launch a battalion of satellites into orbit around the Earth to monitor fires on the ground in real time, then collect all that photographic data and use AI to better identify fires in their critical early stages.

Fire Sat is a partnership between Google, the nonprofit Earth Fire Alliance, and the satellite builder Muon Space. The collaborative effort was announced in 2024 with the goal of launching satellites specifically designed to spot wildfires. The first satellite of the proposed 50-plus strong constellation launched in March 2025.

The group hopes to get the full constellation up there by 2029. Then, the satellites will be able to orbit the Earth, snapping images of every fire-prone place on the globe. The photos would be captured about 15 minutes apart, enough to catch a small fire before it grows too big, or to observe the progress of an active blaze.The information about a fire’s location could then be beamed to data analysts and machine intelligence systems on the ground more quickly than ever.

“We want to make sure that we can learn fast to be able to detect and track fires,” Brian Collins, the executive director of the Earth Fire Alliance, says. “We want to transform the way the world and the United States looks at fire.”

This group’s effort isn’t the only mission to put fire-tracking satellites into orbit right now. The Canadian WildfireSat program is a government-funded effort to launch its own fire-specific satellites dedicated to monitoring blazes across the country. In the 2025 fire season so far, nearly 9 million acres have already burned in the fires active in Canada. But the launch of Canada’s fire satellites is still a ways off, slated for launch in 2029. Google wants to get into space more quickly—and use its AI chops to speed up the process of figuring out when fires start.

Satellites already in orbit have been snapping pics of wildfires for years. Google has incorporated data collected by NOAA weather satellites to show wildfire boundaries and evacuation zones in Maps. But detecting fires from space—especially small ones or fires that are just starting—can be tricky. Satellites currently in orbit tend to detect heat with microbolometer sensors, thermal imaging chips that, unlike other thermal cameras, don’t require cooling. The problem with that, says Christopher Van Arsdale, a researcher at Google, is that microbolometer images can have a narrow field of view and come back with grainier, lower-resolution images. That can make detecting fires in their earlier stages hard, because lots of heat signatures on the ground—hot roofs or even light reflected off water surfaces—can look very similar to wildfires to a thermal camera.

“If you look at a noisy picture, everything kind of looks like a tiny fire,” Van Arsdale says. “So you have to really know what you’re looking at for that to be useful. You need these very high-fidelity pictures in order to actually do a good job with detection.”

Google and Muon’s fire satellites are outfitted with image-capture equipment that works to solve this problem. They will take photos of the same spot using two different types of cameras—one more standard camera that covers visible and short wave infrared and one cryo-cooled thermal camera that takes shots in higher resolution than a traditional microbolometer. Then those images are sent to data centers where Google’s computer vision and machine intelligence prowess comes into play.

“The whole job of the constellation after it collects the data is really to funnel it to a data center where we can take the imagery and analyze it to understand if what we’re looking at is likely a fire or a false positive,” Van Arsdale says. “Fundamentally, the main problem with all of these systems for early detection is separating out false positives.”

By cross-referencing the different photo types and collecting millions of pixels of imagery over time, Google is hoping its AI system will be able to reliably see the forest fire for the trees. The platform can leverage all the imagery from the satellites, collate the different image types, then analyze and compare that information to historical data to look for trends that typically signal the beginnings of a fire.

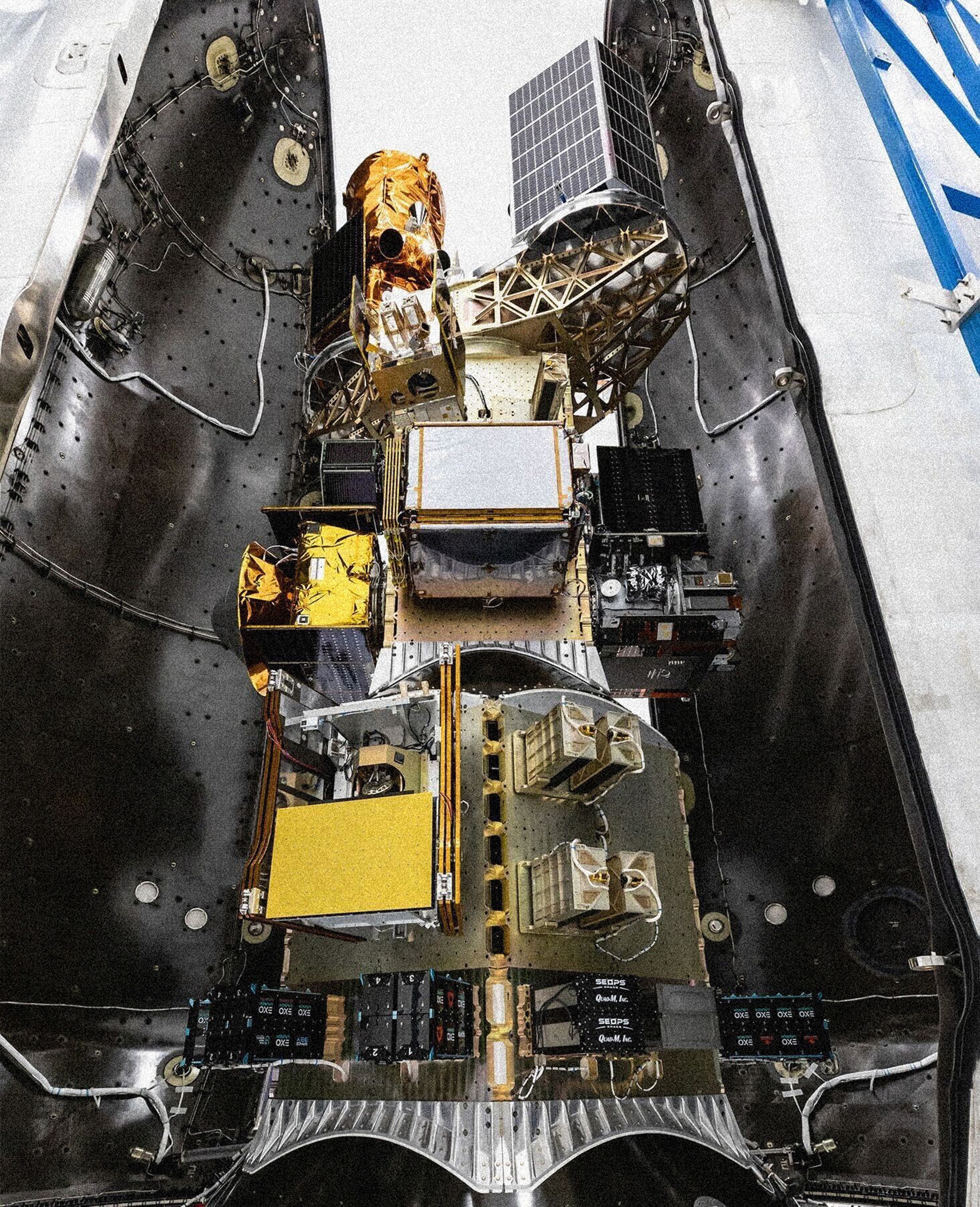

Test Flight

A SpaceX rocket blasts the first of the Fire Sat missions into space.

Courtesy of SpaceX

There is one Fire Sat satellite in orbit currently circling the globe. It captures images and tests what it will take to reliably snap pics of the planet in short enough intervals to track the movements of a wildfire. Google says it plans to show off images captured by the satellite sometime this summer.

The Fire Sat operation plans to launch three more satellites in early 2026, and eventually work up to its final number of 52 satellites over the course of the next few years. At full capacity, the satellites should be able to detect a fire as small as ten square meters and then collect updates on the spread every 15 minutes or so. The goal is that the window between updates is short enough to give them the types of information first responders can actually put to good use.

“With fire in particular, times are compressed so much that you have to apply technology to make a decision within the timeframe that you can impact the outcome of what’s happening,” Collins says.

Krystal Azelton, a senior director at the Secure World Foundation, a nonprofit that advocates for sustainable space policies, says that while satellites and AI tech may provide better data, it’s crucial that the data makes it into the right hands.

“The trend towards AI to assist with all of this is obviously going to produce better results, but it’s not going to produce consistent results necessarily.” Azelton says. “This is a really big positive because one of my biggest concerns about any kind of environmental monitoring from space is whoever’s providing the data, how do you get the data into the end user?” Azelton says. “There’s a lot of tech solutions out there, but how do you get them into the hands of people actually using it?

Van Arsdale says the goal of the Fire Sat team is to make its tracking data as accessible as possible, and it’s committed to working directly with firefighting agencies to do so.

“There’s this sort of fog of war associated with fires, where you don’t know where they are when they start,” Van Arsdale says about trying to pitch the idea of this vast swath of data collection to firefighting officials. “We’re just going to give you a picture of everything that’s going on that you could possibly care about.”

Speed Run

While more information is usually better in disaster situations, it isn’t clear if this kind of satellite detection will be all that much faster than what currently exists. Camera networks like those deployed by AlertWildfire have been the first to spot fires all across the West Coast, including the deadly Palisades Fire in Los Angeles this past January. There’s also the fact that while Fire Sat cameras may be able to pick up a fire the moment it starts, just having that information doesn’t mean firefighters will be able to mobilize and get to the blaze in time.

Daniel Swain, a climate scientist who runs the blog Weather West and has long tracked wildfires, says that while satellite-enabled updates may not solve all the realities of response time, it would be useful for sharing information with people in immediate danger and keeping people informed as the fire spreads.

“It doesn’t really solve the core underlying problems, but it’s probably a beneficial thing to do,” Swain says. “It does help to know exactly where a fire is as soon as possible. It unfortunately doesn’t give us much of an edge under the most extreme conditions.”

These Fire Sat efforts also come at a time of increased investment in the tech aimed at fighting wildfires. Namely, an uptick in private companies hoping to help build new firefighting solutions—and profit off that tech. In June, President Trump signed an executive order for a “common sense” approach to fighting wildfires, which called for prioritizing the efforts of fire tech companies while also combining federal disaster agencies and instructing federal agencies to “declassify historical satellite data to improve wildfire prediction and revise or eliminate rules that impede wildfire detection, prevention, and response.”

That focus, along with the sweeping cuts to federal disaster programs like FEMA and the US Forest Service means that with fewer public resources to tackle the problem, private industry is moving to close those gaps.

Swain cautions that while lots of this tech might be helpful, relying on private companies to solve widespread societal problems like disaster response comes with problems.

“Even if you assume the best possible motive,” Swain says. “That this is truly in the public interest and that private companies are able to effectuate that, there’s then the question of, OK, are we actually going to have access to this data in the long run, or is this going to be the equivalent of a 30-day free trial?”

He points out that internet-of-things companies have gone out of business and left customers with products that no longer work, and that Google itself has a long history of killing off services.

“It’s the classic tech industry challenge of continuity,” Swain says. “We’ve seen this happen.”

Azelton believes there will always be a need for “a baseline of government, truly and fully public data that’s out there, that’s accessible to anybody and everybody that can and should be supplemented by commercial data and partnerships like this, and that they need to be designed in a way that they can be in the hands of everyone who needs them.”

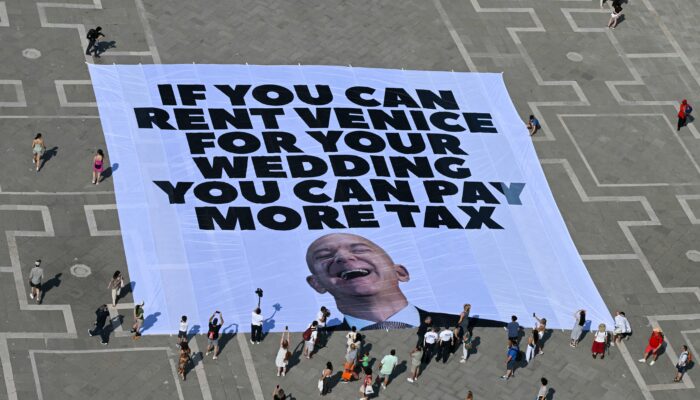

It’s a feat that Google seems keen on facilitating, even if it isn’t immediately profitable for the company. It’s also easy to see this as a sort of mea culpa for Google, a company that has made a number of climate commitments, despite the fact that, like all purveyors of generative AI technology, it consumes lots and lots of energy. (In 2024, Google’s emissions bumped up by 50 percent because of its generative AI efforts.) Humanity’s ever increasing consumption of energy has worsened climate change, which has in turn played a part in worsening wildfires.

“If Google admits, you know, what we do harms the planet, but we’re trying to find ways of stewarding as well, and these are the ways in which we’re trying to be regenerative and restorative,“ says Moriba K. Jah, a professor of aerospace engineering at the University of Texas at Austin. “At least having a more honest conversation about it I think would be refreshing.”

In late May, Google highlighted the Fire Sat program very briefly at the end of its I/O developer conference. It was a real tonal shift, a blink-and-you-miss-it moment of environmental angst and self-congratulation after a two-hour deluge of breathless AI-fueled futurism. Maybe launching enough satellites to keep track of all the damage is an effort to atone for the vast energy AI uses. Maybe it will even work.