Cuts made by the Trump administration are threatening the function of a tiny but crucial office within the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration that maintains the US’s framework of spatial information: latitudes, longitudes, vertical measurements like elevation, and even measurements of Earth’s gravitational field.

Staff losses at the National Geodetic Survey (NGS), the oldest scientific agency in the US, could further cripple its mission and activities, including a long-awaited project to update the accuracy of these measurements, former employees and experts say. As the world turns more and more toward operations that need precise coordinate systems like the ones NGS provides, the science that underpins this office’s activities, these experts say, is becoming even more crucial.

The work of NGS, says Tim Burch, the executive director of the National Society of Professional Surveyors, “is kind of like oxygen. You don’t know you need it until it’s not there.”

“NOAA remains dedicated to providing timely information, research, and resources that serve the American public and ensure our nation’s environmental and economic resilience,” NOAA spokesperson Alison Gillespie told WIRED in an email when asked about the downsizing of NGS.

NGS was formed in 1807 by Thomas Jefferson, the son of a surveyor and cartographer. Originally called the Survey of the Coast, the organization, led by a young Swiss immigrant named Ferdinand Hassler, was tasked with mapping the coastlines of the new country. Over the next 200 years, its mission expanded to cover the practice of geodesy: the science of calculating the shape of the Earth, its orientation in space, and its gravitational field.

“Hassler understood that before you put pen to paper and make a chart or a map, if you wanted to [know how] things relate accurately one to another, especially if you’re going to do that over a large area like the United States, then you have to have a very strong mathematical foundation to put all these pieces together,” says Dave Doyle, a former chief geodetic surveyor at NGS. “That is, in a very simple way, what the science of geodesy brings to the nation.”

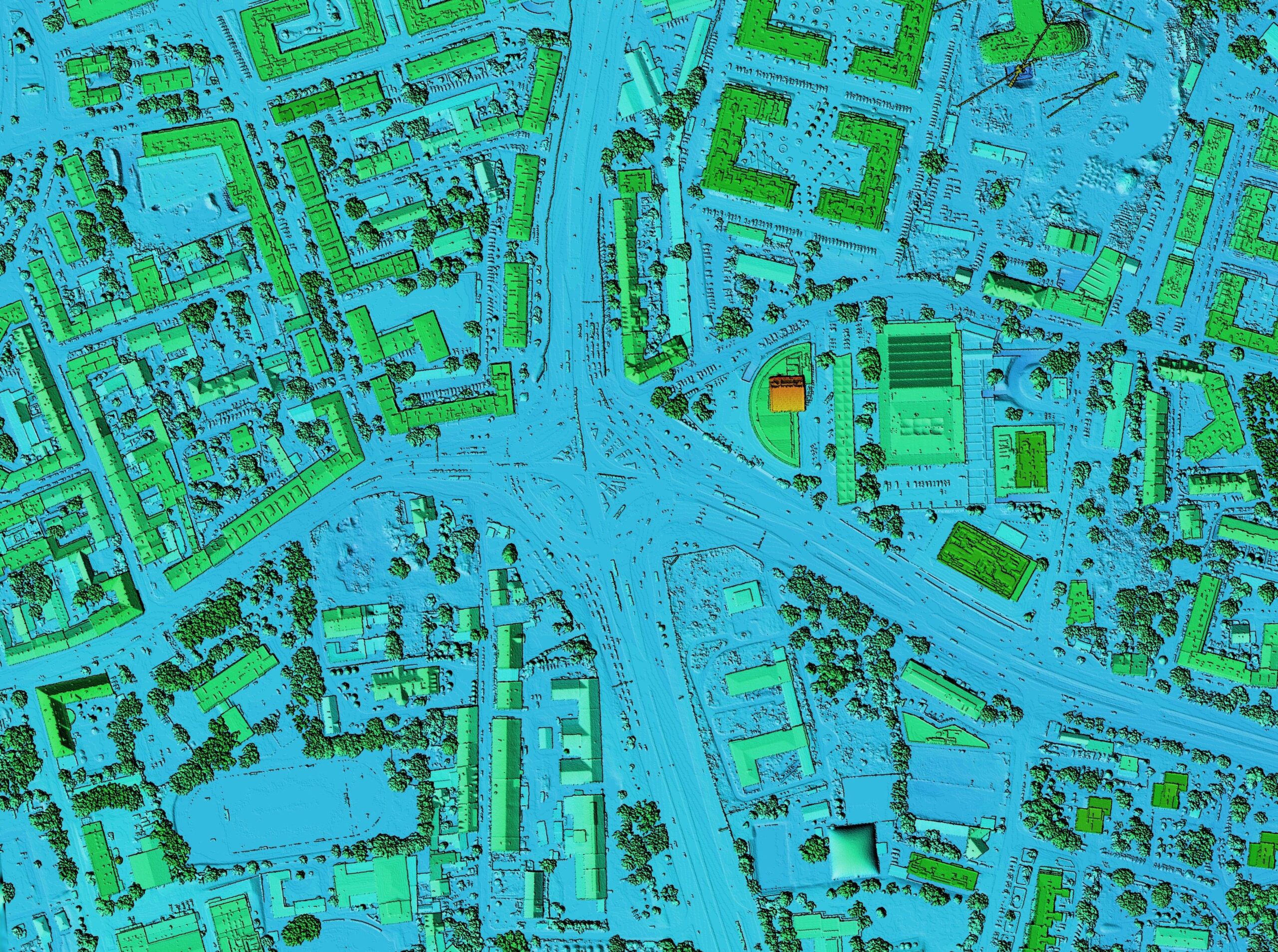

NGS is currently responsible for maintaining and updating what’s known as the National Spatial Reference System, a consistent system of physical coordinates used across federal and local governments, the private sector, and academia. This includes not only latitude and longitude, but also measurements of depth and height as well as calculations around Earth’s gravitational field—crucial mathematics that inform much of the basic infrastructure around us, from constructing bridges to mapping out water and electric lines. NGS also maintains and operates more than 1,700 federally owned satellite receivers across the US, which provide publicly available geospatial information.

While individual surveyors can compare heights and distances in smaller areas, it’s far more difficult to compare mountains thousands of miles from each other, or know exactly how sea level rise may be affecting different areas of the country that have vastly different coastlines. Having a coordinated frame of reference across the entire country—both latitude and longitude as well as depth and height—underpins the accurate positioning of locations across the US in relation to each other, as well as in relation to other geospatial measurement systems across the world.

The Earth is also constantly shifting: the motion of tectonic plates causes latitude and longitude coordinates to slowly move, mandating that they be updated every few decades. In some places—like the coast of Louisiana, where subsidence is causing between 25 to 35 square feet of land loss each year—these shifts manifest much quicker.

“Most people can stand on the beach and see the water and turn around and look at a dune behind them and go: ‘Oh, yeah. That’s about 5 or 6 feet above sea level,’” says Doyle. But when it comes to building things, you need to be able to accurately take measurements at scale. “You have to have some system of heights that is standardized across a large geographic body. I want consistent heights from New York to Maryland so we can build highways, so we can build utility infrastructure. You want to make sure water is always flowing in the appropriate direction.”

The US is currently working with a particularly outdated set of coordinate systems. The current measurements contained in the National Spatial Reference System—including latitude, longitude, and vertical heights, a set of reference systems called datums—were established in the 1980s, shortly after the US launched the world’s first GPS satellites. In the years since those datums were created, increasingly advanced satellite technology has enabled geodesists to more accurately measure the shape and orientation of the Earth, and to better position their measurements. As a result, each point of measurement in the US datums is now, on average, around two meters off from its actual, accurate location. In some locations, it’s even more extreme.

As anyone who has tried to go for a run with a glitchy Garmin watch knows, current GPS technology has limits in terms of on-the-ground precision. For everyday navigation, exact locations aren’t truly necessary—but for a variety of activities, from mapping floodplains to building bridges to measuring sea level rise, every centimeter becomes crucial. Ensuring hyper-accurate location is also becoming increasingly important as more and more industries are building up around automation that relies on precise spatial measurements.

“Do you want to get in an autonomous taxi that is plus or minus two and a half meters going down the road?” says Burch. “I don’t. That is part of the critical piece here: all these systems have to be this tight and this precise moving forward.”

In order to update the US’s datums to be in line with satellite data, land shifts, and accurate measurements of the Earth, staff at NGS were planning on rolling out a long-awaited modernization of the National Spatial Reference System, bringing it into the 21st century and making it easier to update moving forward. Originally scheduled to be completed in 2022, the agency posted a notice in the federal register last fall detailing its updated timeline for rolling out the new datums and associated products in 2025 and 2026.

But three former staffers who left NGS in the past month say this planned rollout may be pushed even farther behind by staff losses, thanks to employees like them who took retirements, left their jobs, or were laid off as part of federal restructuring. According to former staff, NGS was sitting at 174 employees at the start of the year, with staff looking to fill an additional 15 positions to help with rolling out the new datums and educating federal agencies and local governments on their use. Since January 20, the agency has lost nearly a quarter of its staff and has had to freeze planned hiring. (When asked about the accuracy of these numbers, Gillespie, the NOAA spokesperson, told WIRED that the agency has a “long-standing practice not to discuss personnel or internal management matters.”)

The remaining staff are in an “all hands on deck” situation with the rollout, says Brett Howe, the former geodetic services division chief at NGS, who opted to retire at the end of April. Despite a dedicated staff, Howe says that the loss of many in senior leadership with decades of experience and institutional knowledge means that the agency can’t afford to go through any more cuts.

“If we get to hire back some people, we are still going to have trouble meeting that timeline of 2025 and 2026 [for the rollout], but we’ll be able to make it work,” he says. “If there are further cuts, or we’re not able to execute our [National Spatial Reference System] modernization plan, and then we get to a year, a year and a half from now, and we lose more people—either through other layoffs or they just retire—then I think we’re in real trouble. Then I wonder how we function as an agency.”

“At this time, the ongoing NSRS modernization plans are still aligned with the dates in the Federal Register notice,” Gillespie told WIRED. “NGS will be releasing foundational data and supporting products for testing and feedback in 2025.”

The fate of NGS under the Trump administration is unclear. A NOAA budget proposal from the White House Office of Management and Budget sent to the agency in April cuts the budget for the National Ocean Service, which houses NGS, by more than half. Project 2025 does not mention NGS by name, but it does mandate moving NOAA’s surveying capabilities to other agencies.

“We don’t speculate about things that may or may not happen in the future,” Gillespie said when asked about potential upcoming changes to the agency. “NOAA will continue to deliver weather information, forecasts and warnings, and conduct research pursuant to our public safety mission.”

The sharp drop in staff numbers at NGS is the tail end of a long decline for the practice of geodesy in the US. In 2022, a group of leading geodesic experts authored a paper on what they dubbed the US’s “geodesy crisis,” detailing how other world powers have invested in training geodesists over the past three decades while the US has wound down funding and training. China has invested particularly heavily in creating more geodesists: the country graduates between 9,000 and 12,500 geodesy students per year, many of whom are then employed by the government. By contrast, around 20 students graduated with advanced degrees in geodesy from US universities over the past decade.

This, the authors argue, has contributed to China rapidly overtaking the US in geospatial technologies and disciplines of all kinds. Nowhere is this clearer than with China’s satellite navigation system, BeiDou, which has been gaining on the US’s GPS system in accuracy. In 2023, a US government advisory board on GPS stated in a memo that GPS is now “substantially inferior” to BeiDou.

Like other cuts to public science made under the Trump administration, the losses from blows to this agency could be substantial. A 2012 analysis found that every taxpayer dollar spent on NGS’s coastal mapping program returned $35 in benefits, while a 2019 report found that the NGS program that models gravitational fields would provide between $4.2 and $13.3 billion worth of benefit over 10 years. The private sector also relies heavily on public data provided by NGS. Some analyses project that the geospatial economy will grow to $1 trillion by the end of the decade. It’s even more crucial, experts say, to have an updated spatial reference system in the US, as well as institutional knowledge of the basic science of how to measure and understand our Earth.

Many industries now “want that high accuracy positioning” that comes with advanced geospatial technology, Doyle says, “yet they don’t understand the basics of the science. Now you’ve got all these people punching buttons and getting numbers, and only a tiny percentage of them really understand what the numbers mean, and how one set of numbers relates to another.”