This is a segment from The Breakdown newsletter. To read full editions, subscribe.

“If this all seems like a wild idea, that means you understand it.”

— Ted Nelson

If internet-native money existed in the 1970s, today’s newsletter would cost $0.001 to read.

Instead, it’s free.

Ted Nelson thinks that’s a world-changing disaster.

Nelson is the philosopher, media theorist and tech-visionary who, in 1960, first conceptualized a global “docuverse”: a vast, interconnected library of information made available by networked computers that did not yet exist.

Incredibly, that was nine years before the first computer-to-computer message was sent over the ARPANET.

Nelson prophetically explained that we’d soon access our information via computer screens, which seems intuitive enough — but he was explaining it at a time when hardly anyone had seen one.

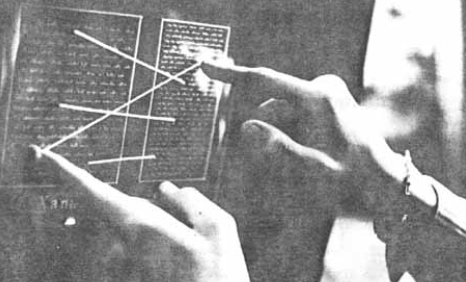

He had to make cardboard and celluloid mockups of computer terminals to try to make his “Project Xanadu” comprehensible to people:

Nelson imagined those screens displaying “visible connections” between every piece of information: a universal system of permanent, unbreakable, two-way links between all the world’s documents, stored on networked servers that anyone could access.

That was 29 years before Tim Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web — which Nelson is still unhappy about.

“I don’t want to talk about the Web,” he told an interviewer in 2021. “I hate it.”

Nelson dismisses today’s Web as a dumbed-down version of Xanadu, stripped of its most important parts: visible connection and micro-payments.

“The World Wide Web was my idea in the 1960s,” he later groused. “That other system caught on. The great disappointment of my life.”

Nelson is particularly disgusted by Berners-Lee’s now-ubiquitous hyperlinks, which he derisively calls “jump links” — a blind, one-way leap into an ocean of disconnected digital documents that simply “imitate paper.”

(In Nelson’s honor — and possibly to your confusion — I’ve refrained from including any hyperlinks in today’s article.)

To Nelson, building the Web in imitation of paper was no more imaginative than building cars in the shape of horses.

Project Xanadu promised instead a revolutionary version of the Web with “visible connections between pages,” two-way hyperlinks and “micro paywalls.”

This, he promised, would reflect the “nonlinear” nature of human thought, and thereby advance human creativity and progress — all while fairly compensating the world’s inventors, thinkers and content creators, one micro-payment at a time.

In short, Nelson wanted computers to be organized the way people think, and what we got instead is the opposite: a World Wide Web that makes people think the way computers are organized.

“Calling a hierarchical director a ‘folder,’” he characteristically argued, “doesn’t change its nature any more than calling a prison guard a ‘counselor.’”

He wasn’t speaking in metaphor: He really does think computers are a prison for the mind.

“I’m very unhappy about the Web,” he added in 2021, “but now we’re stuck with it.”

But maybe not for too much longer?

One reason you’re not paying $0.001 to read this newsletter on Xanadu is that Nelson’s lofty ideas were conceived decades ahead of the technology needed to realize them.

Even after the internet and the Web were invented, Project Xanadu would have required far more computing power, storage capacity, and networking sophistication than anyone thought possible.

Berners-Lee’s “dumbed down” version of the Web won out for one simple reason: It was possible.

Nelson’s vision of attributing all content to its original source, for example, was unfeasible because of the power and storage it would have required was unavailable.

His vision of compensating every idea with micropayments of royalties and sub-royalties was unfeasible because there was nothing to make micro-payments with.

But in 1989, Berners-Lee at least nodded at Nelson’s vision by including the status code “402: Payment Required” in his world-changing HTTP protocol.

402, as it’s known, would have allowed web servers to demand payment from a visiting browser before granting access to a document, video, song or idea.

Unfortunately, browsers, not being allowed bank accounts, had nothing to pay with — and even if they had, the process would have been too slow and too expensive to be useful.

Things have since changed, of course: Internet-native money was invented in 2009; onchain dollars were invented in 2014; and in 2025, high-throughput blockchains have reduced transaction times to a fraction of a second and transaction fees to a fraction of a cent.

In other words, everything is finally in place to realize Nelson’s “system of commerce that would create viable ways for people to be paid with a sensible and completely fair method.”

It won’t happen quickly.

For one thing, we’ve gotten thoroughly accustomed to internet content being mostly free, so ads are unlikely to be replaced by micropayments anytime soon.

Nor is online shopping likely to change: Credit cards work just fine for occasional purchases (also, we love our air miles).

But Ted Nelson’s original vision anticipated a problem that’s only now become evident, 60 years later: language models scraping the entirety of human knowledge from the internet and reproducing it without attribution.

This is exactly the future that Nelson was trying to prevent: a world where ideas were brutally detached from their creators and copied endlessly without context, credit or compensation.

I’m not sure anyone other than Nelson has even suggested a solution.

Project Xanadu — started in 1960, never a working project and long dismissed — somehow remains a futuristic vision.

To finally realize that vision, the Web might have to be reorganized along Nelson’s principles: with visible connections that allow all the world’s information to be properly attributed, and micro-paywalls so they can be properly compensated.

“I believe the original dream is still possible for everyone,” Nelson said in 2021. “ But not with today’s systems.”

With today’s systems, however, it might be.

Get the news in your inbox. Explore Blockworks newsletters:

- The Breakdown: Decoding crypto and the markets. Daily.

- 0xResearch: Alpha in your inbox. Think like an analyst.