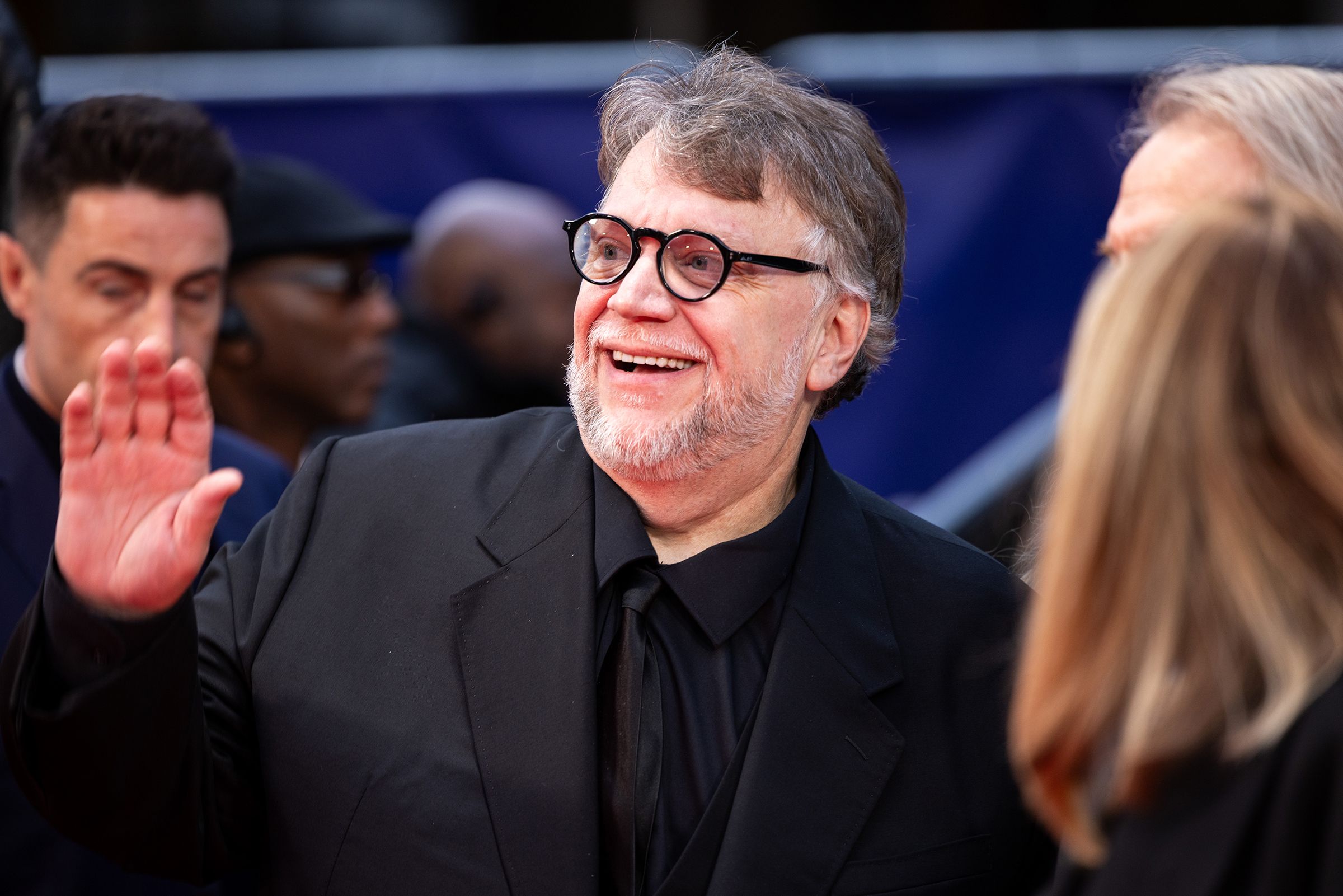

Guillermo del Toro loves a challenge. Nothing the 61-year-old director does could be termed “half-assed,” and each of his movies is planned, scripted, and storyboarded with immense attention to detail.

Such discipline is evident in Frankenstein, his adaptation of Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel. It’s a movie del Toro has been trying to make for years, and it shows. The elaborate sets and costumes—as well as some embellishing of Shelley’s story—could only be the work of someone as connected as he is with his source material.

Raised in a deeply Catholic family in Guadalajara, Mexico, del Toro was so enthralled when he saw the 1931 Frankenstein film at age 7 that he opted to make Dr. Victor Frankenstein’s creature his “personal messiah,” he told NPR. Since then, he has made a career out of transforming so-called “monsters” into heroes—from the kaiju of Pacific Rim to the fish-man of The Shape of Water, the latter of which earned him Academy Awards for Best Director and Best Picture.

Frankenstein, which is currently playing in select theaters and will hit Netflix on November 7, marks the latest and probably most extravagant of del Toro’s love letters to mistaken monsters. WIRED hopped on Zoom with the director to talk about AI, tyrannical politicians, and the fateful summer in 1816 during which Shelley was inspired to write the book he treasures so much.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

ANGELA WATERCUTTER: I’d like to begin at the ending. You close Frankenstein with a quote from Lord Byron. “The heart will break, yet brokenly live on.” You’re adapting Mary Shelley. Why give Byron the last word?

GUILLERMO DEL TORO: Well, to me, the movie is an amalgam of Mary Shelley’s biography, my biography, the book, and what I want to talk about with the Romantics. One of the strands that I felt was missing, but very present, was war. Basically, the metronome of their lives is in many ways the Napoleonic Wars, and this is part of Byron’s poem for Waterloo. There’s no better way to express what the movie’s about than that quote. This comes from a very personal experience for me. The fact that your heart will be broken, you will be pulverized, and the sun will rise again, and you’re going to have to keep living.

Byron is also the one who provoked Shelley to write the book. He was with her and Percy Bysshe Shelley and writer John Polidori on Lake Geneva when they had a competition to write the best horror story. She came out with what was probably the best of the bunch.

I like The Vampyre by Polidori. It’s really raw and full of the desire and hatred he had for Byron. [Laughs.]

I recently came across a story I’d never heard before, which was that Shelley allegedly kept Percy’s heart after the sailing accident that took his life.

No, it is not allegedly. It is a fact. The death and funeral of Percy Shelley, which has been mythologized into an almost hagiography piece, is that after he died he looked as if he was asleep. Really, when they rescued him, he was rotting away. He was falling apart. They had to hire soldiers and sailors to drag the chunks of his body. I don’t know if you know this, but in a cremation, one of the last things to burn is the heart, because it’s such an incredibly strong muscle.

I didn’t.

Shelley’s heart passed from hand to hand but ended up on Mary’s desk. Yeah, that’s a fact. [Editor’s note: While some disputed it was his heart, Shelley and her friends believed it to be her husband’s organ.]

When I saw the Byron quote at the end, I thought that might have been what you were referring to.

Her allegiance to Percy beyond the grave is very, very moving. The fact that they eloped when she was 16 is crazy to me. They were basically like a band of punks.

Bringing this back to the book itself, why tackle something so well-known? Obviously, you do it in your own style and bring a lot of new elements in. But Frankenstein has been adapted a lot.

Look, I think you can tackle any of the eternal tomes. I’ve done it with Pinocchio; I’ve done it with Frankenstein. I think they get renewed.

This is not your run-of-the-mill Frankenstein with the mad scientist and the creature grunting his way around, being chased by villagers with torches. This is very true to the spirit of the novel. This is divided in an almost epistolary form into different very, very separate sections of narrative with very particular voices. The narrative that frames the movie, which is the furthermost North. Then you have Victor telling his story of childhood, his youth, and then the Creature comes in and brings an almost fairy-tale or parable feeling to the movie. All I can say is what’s new is me.

Do you see a modern relevance or resonance with the story of Frankenstein? The idea of someone trying to play God and bring something into the world, perhaps against better advice.

I happen to not believe that the novel is anti-science. The Goodwin-Shelley household of Mary’s youth was really pro-scientific. I think that Frankenstein is actually closer to Paradise Lost. It’s man rising up to God and saying, “Why am I here when I didn’t ask to be born?” Which is a very romantic—and by romantic, I mean the Romantic movement—question.

Yeah. Victor is someone who believes very much in science, but he’s also tragic. He almost doesn’t ever confront what he’s done.

In fact, there is a big harangue Victor does in the book toward the sailors saying, You should follow your captain all the way. He is not repentant.

Now, in my opinion, the arrogance of Victor is very common now: the tyrant that believes himself to be a victim. But that is true, or has been true since the beginning of time.

What would be some examples for you?

Absolutely everyone from political figures to Silicon Valley tech bros. You name it. Including artists and film directors. The fact that we enthroned tyranny as a form of certainty, as if it was an attribute. I think the people I most admire are people that are riddled with doubts. Certainty and self-victimization oftentimes go hand-in-hand.

When I think about playing God, I also think of AI. Which is also perhaps something that never asked to be born. You’ve been an outspoken critic of AI. Do you see parallels between the makers of AI and, say, Victor?

I was not interested in making any [in this film]. I understand [using] it in engineering and biochemistry and mathematics, because those are permutations. In art, I don’t think anyone asked for it. Nobody raised their hand and said, “Could you invent this?”

No one asked for Sora.

Look, the real threshold has not been crossed. It’s not people making this, it’s people consuming it—at a cost. I will gladly pay $4.99 for a song by the Beatles or Dylan, you name it, but who is going to pay $4.99 for something created with AI? When that threshold is crossed, then we’ll see.

Do you think that’s possible?

I don’t know. I mean, I’m extremely glad I’m 61. So I don’t have to worry about this. With a little bit of luck, I’ll die before that takes root. I’m much more interested in talking about anything you want except that.

I’ll change the subject. You recently said that you were glad to have made this as a father yourself rather than the son of your father. Could you talk about that.

Well, it happened during the decades. I think that you start pondering the power of forgiveness at a certain age. You have to be an adult to understand somewhat that your father is a guy. Your mother is a woman. They’re fallible. They are full of their own tragedy and history. But for you, at a totemic level, they’re gigantic shadows. The more you age, the more you realize it is not an occupation. This is something that is foisted upon them by life. And there’s a moment where you understand that the lineage of pain can pass or can stop with you.

You obviously admire Shelley a great deal. Do you feel like she wasn’t given the credit she was due when she was alive because of her gender? Given that Frankenstein is so much about fathers and sons, it’s telling that it was written by a woman.

The first thing is, although the figure of a father is not very present in the novel, it is in the rest of her work. Her last two novels deal with tyrannical father figures, almost antagonistic to a large degree. And her relationship with her father was, to say the least, tense.

Number two, the fusing of birth and death, which happens from her mother onwards, including her own infant deaths and miscarriages. It’s very powerful in the sense that she almost muses about the granting of life without female agency.

I don’t want to venture a Freudian thesis or anything, but having gone through a similar past—my grandmother died after my mother was born; my mother had a series of miscarriages to the point where I feared the arrival of a new sibling because I thought my mother is going to die—that is very present in my movies. So there’s a kinship that I feel exists there.

I think of you as somebody who’s very forward-looking, someone who has ideas about where cinema has been and where it should go. At a time when studios are merging and making moves to streaming, what do you see happening in the industry going forward?

I don’t know. I think that anytime you venture something, the landscape changes. There was a moment five years ago where every single studio had a streaming arm.

As an industry, the guiding principle is more commercial. As an art form, it is so diverse and beautifully alive that things happen in the most unexpected places. Even when you think about streaming, the fact is more often than not it is the anomaly that prevails. Baby Reindeer, Squid Game—these things that come out of nowhere are the ones that end up really dispersing over hundreds and hundreds of millions of homes. That didn’t exist before.

Does that mean we’ll be seeing another stop-motion project from you? It’s hard to believe your Pinocchio was already three years ago.

The next project is stop motion, but my interest with stop motion is to move it away from the children’s table and making it into an art form that can discuss R-rated or PG-13 [topics]. I’m adapting Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Buried Giant. That’s hardly Disney. My interest with the form is very different and has always been, and my interest with horror or fantasy is very different. I think the stop motion that I am hoping to see flourish is closer to the European model than the American one.

What’s the status of The Buried Giant? Do you have a script? Your preproduction process is always so involved when it comes to concepts and storyboarding, so I’m wondering what the timeline looks like for something like this.

So we went into a really serious investigation of the mechanicals on the faces, and we’ve been at it for about eight months, nine months. We have made some progress, and we are doing research on the textiles to miniaturize some stuff that is not easy to miniaturize. I’m writing the screenplay. I’ve presented some pages to the studio. We’re going to do some tests and storyboarding of that and then hopefully next year will start shooting.

We talked a little bit earlier about Frankenstein being something that you had been wanting to make for a while. Is there still something else on the shelf that you’ve always wanted to do? I feel like I interviewed you 10 years ago and you were saying you wanted to do H.P. Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness. What other dream projects are still out there?

I have written or cowritten about 42 screenplays, and I’ve done 13 movies, about twentysomething movies that have not been made. Now, for a lot of them, you grow in a different direction than you were back then when you wrote them. I mean, I am actually tempted to look for something different. To try tools that I normally don’t try, including with The Buried Giant, trying to push the technology and the form of stop motion a little bit.

Would you ever do something totally out of your wheelhouse? Like romantic comedy?

I want to do crime if I can.

I think a lot of people would want to see a Guillermo del Toro noir film.

I’m not talking about noir. I just think crime is so interesting, because it allows you to investigate human nature. I’m very intrigued by that. In my library, the main library is fantasy, and the second most numerous is crime.

Please make a movie of the robbery at the Louvre. I can’t stop thinking about that.

[Laughs] That robbery was a lot simpler than anyone figured.

It was just a lift on a truck and a couple mopeds, basically! Regardless, I’d love to see a del Toro crime film.

Well, I’m writing one for Oscar Isaac, Fury. I just don’t want to look backwards. I want to look forward to seeing what else is out there I can do.