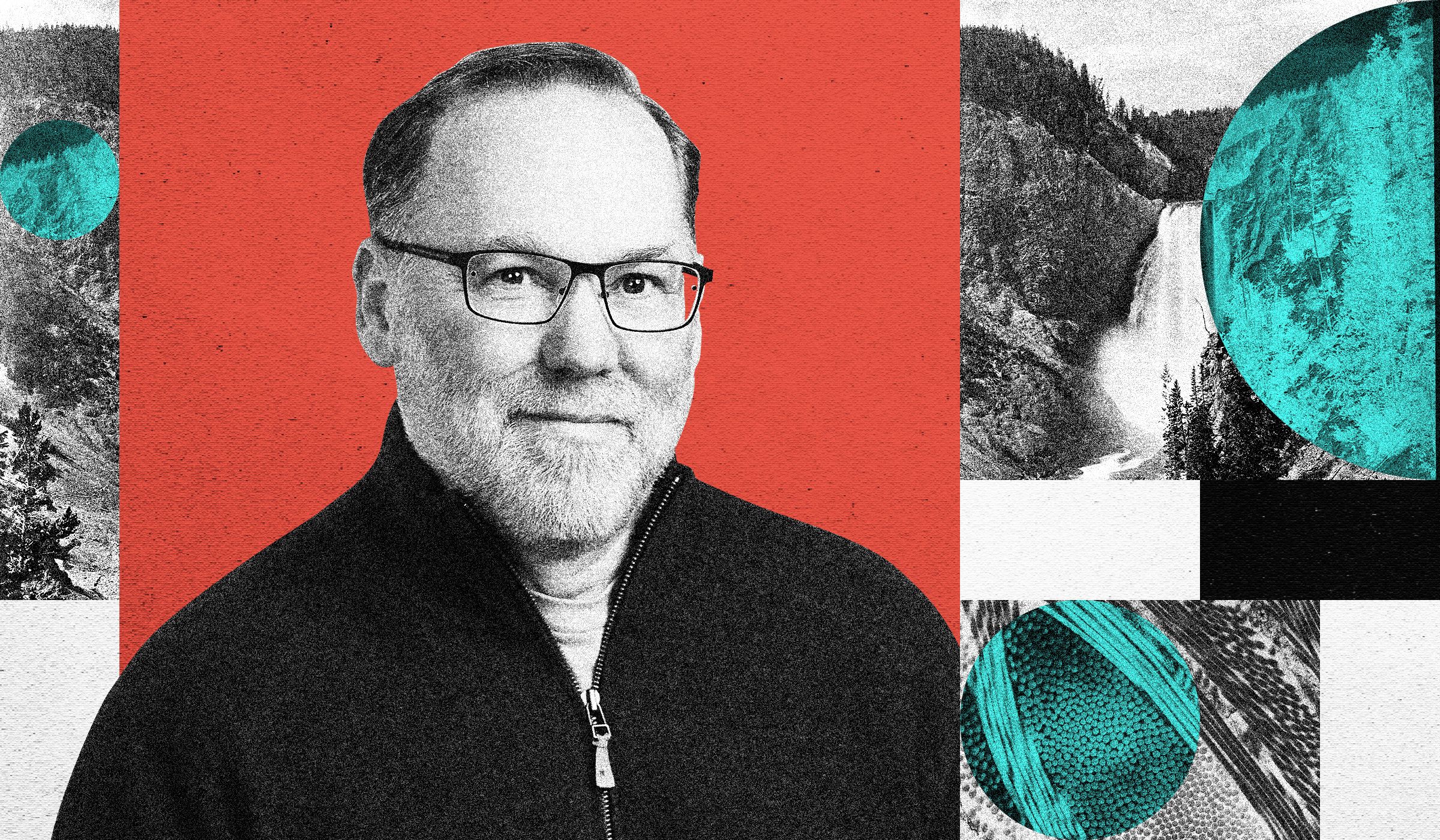

When Fred Ramsdell, 64, was named a Nobel Prize winner earlier this week, he was deep in the Wyoming mountains, blissfully offline and surrounded by fresh snow. The next day, as he was wrapping up a three-week backpacking trip with his wife, her phone began to light up with hundreds of messages about the good news: Ramsdell, along with Mary E. Brunkow and Shimon Sakaguchi, had won the 2025 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their discoveries that reshaped immunology.

Ramsdell tells WIRED he was completely unaware that the Nobel Prizes were being announced, let alone that the Nobel committee was trying to get in touch with him. Sonoma Biotherapeutics, the biotechnology firm he co-founded, told reporters that Ramsdell was “was living his best life and was off the grid on a preplanned hiking trip.”

When the news finally reached him, Ramsdell says he was shocked. He knew that the work he and his colleagues did constituted a major breakthrough, but he had already received another Swedish award for it, and thus assumed a Nobel was out of the question.

Ramsdell and his other co-winners uncovered how the body’s immune system learns to spare its own tissues, a process called peripheral immune tolerance. Part of their work involved a peculiar strain of flaky-skinned mice at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee, descendants of a World War II–era radiation experiment.

These “scurfy” mice were born with a fatal mutation that unleashed their immune systems against their own organs. In the 1990s, Ramsdell and Brunkow, who were working at a Seattle biotech company, identified the gene responsible—a breakthrough that paved the way for today’s generation of cell therapies that target cancer as well as other diseases by retraining immune cells rather than destroying them. WIRED spoke to Ramsdell on Tuesday, soon after he was informed about his Nobel win.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

WIRED: Where were you when you got the news that you won the Nobel Prize?

Fred Ramsdell: I was at about 8,000 feet in the mountains of Wyoming, just a little bit east of Yellowstone National Park. My wife and I had been out for three and a half weeks camping and backpacking and hiking and stuff, and it was our last night, and we got six inches of fresh snow, and so we managed to get out, which was not as easy as I thought it was going to be. We then drove through Yellowstone, and I didn’t pay any attention to my phone, because I’m on vacation. I didn’t even know it was the day they announced Nobel Prizes because I don’t think about that.

My wife’s phone blew up when we went through some little town and she got some signal. She kind of yelled, “Oh my god, oh my God.” I was outside and we’re in grizzly territory, and I thought, “Bear? There’s no bear.” She comes out and says, “You just won the Nobel Prize.”

“No, no, come on,” I said. She’s like, “I have 200 text messages.” I stand corrected, apparently. We already booked a hotel room for that night. So we checked in, and I got online, and I tried to call the Nobel Committee. And of course, it was 1 in the morning there by then, so they were all asleep, so I didn’t talk to them until probably 1:30 am. My wife, Laura, and I went out and we sat in an Irish pub and, you know, had a cocktail or two and some food and watched Monday night football.

Did you at least have a nice dinner at the Irish Pub? It was probably a pretty small town if it was near Yellowstone.

It’s a cute little town. I’d love to go back and spend more time, but no, it was just, “Let’s just go get something to eat,” because I gotta get back—I got a lot of things to do.

Did you tell anyone in the pub that you won the Nobel Prize?

I did not tell anyone, haha. I didn’t think I needed to do that.

You said you don’t follow the Nobel Prizes. How shocking was it to you that you won? I’m assuming you’re aware of how big of a breakthrough your discoveries are, but did you think, well, there’s a lot of great science happening?

I’m not quite that naive. The main reason I didn’t think it would ever happen is that about eight years ago, I along with Shimon Sakaguchi, who was another one of the co-lauterates for this, and then another very good friend of mine who does amazing work at the Sloan Kettering Institute, we won the Crafoord Prize, which is also from the Royal Swedish Academy. It’s a family foundation thing in Sweden.

We went over in, I think, 2017, and it was a great time. You know, speeches, we met the crown princess. It was amazing. And so I thought, OK, that is the recognition that this particular scientific discovery is going to get, which was awesome. So I’m like, that’s better than I could have ever hoped for. People would talk about the Nobel, and I would be like “I don’t think so.” And after that, I was like, “It’s never gonna happen, don’t even think about it.” So I was truly shocked when I heard about it.

Why do you think you received the Nobel Prize for this work now? Do you think it’s because of increased interest in immunology due to Covid? Or is it because these discoveries have now made hundreds of new medical trials possible?

So, I don’t know the answer to your question. If I were to speculate, which is what you’re asking me to do, I would suggest it is mostly the latter. We knew the implications of these discoveries 25 years ago, but the technologies didn’t exist to create the drugs that we can create today, and even if they did exist, there was going to be no appetite for an expensive, totally novel cell therapy approach to autoimmune disease 25 years ago. So I think it is this turnover of this idea now becoming practical.

What were the technological developments that made it possible to create these cell therapy treatments?

I will give a lot of props to my friends and colleagues in the oncology world, Carl June and Michel Sadelain, and others who I know, because they really pioneered the entire concept that you could take a cell out of a person’s body—in their case, a cancer patient—engineer it in the lab, and put it back in and have it do something that is, frankly, remarkable. And there’s products on the market now, in fact, they got there pretty quickly, because they were such remarkable products. It’s all still ongoing, but they showed, I don’t want to sound crass but, that making a commercially viable thing that patients would take, that payers would pay for—it was actually worth the hassle.

So I have to ask you, how did you come across the genetically mutated mice from the Oak Ridge Laboratory?

So that’s a great question. And I love the fact you know it’s Oak Ridge, you’ve done your homework. So the way we came across this is I joined a small biotech company in the Seattle area in ’95, something like that, and the CEO was a gentleman named David Galas. And David had a long academic history at USC as a molecular biologist, physicist, and eventually, he ran the Oak Ridge National Labs, I can’t remember exactly what it’s called, but the center for mammalian genetics that was set up by the Department of Energy. It was set up during the Manhattan Project to understand the effects of ionizing radiation on mammals. And so he knew about this program.

There were lots of strains of mice that had varying phenotypes, some had neurologic changes, some had musculoskeletal changes, coat color changes, all sorts of things. The one that we became interested in, and it was David, and it was my boss at the time, and a colleague and friend named Steve Ziegler, who looked at this mouse and said, “Wait a minute, that mouse has rampant, uncontrolled autoimmune disease.” Its T cells see every tissue in its body basically and just go at it, and the mice die three weeks after birth.

If the lab was set up during the Manhattan Project, does that mean the studies you were looking at were 40 years old? Or did the Department of Energy continue to breed these poor mice with scaly skin?

That’s correct, they kept breeding these poor mice. It’s a pain honestly, and they did it for 40 years because they knew these were really important mice, but they didn’t have the capability to sequence the genome to find the gene. And so when we saw them, we started a collaboration and said, we can find this gene. And we did, and that’s actually mostly the work of Mary Brunkow, one of my other co-laureates and again, a very good friend of mine. She and I were at the same company. She cloned this gene.

Now, it took another 20 years to flesh everything out, and that’s not just dotting i’s and crossing t’s. There was a lot of very complicated biology that was done by people like Sasha Rudensky and many others in the field, Jeff Bluestone and many others. But once we had those pieces together, it was pretty easy to say, “OK, this is the cell, and this is the molecular mechanism that we need to utilize to control autoimmune disease.”

Your discoveries are a testament to the importance of scientific collaboration and investing in long-term research. Do you think you could have made these discoveries without the wider research ecosystem you are part of?

When you tap into the research ecosystem correctly, it’s incredibly powerful. I’ve been in biotech my whole life, because I actually really loved the power of team science. And when I left my postdoc at the National Institutes of Health, I went to a biotech company in Seattle because they had the best molecular biologists and they had cell biologists that were as good as anybody in the world. I had a ton of resources, and I became a resource for them. It was a team goal to understand how things work and at some point that will turn into something useful for patients.

And I will say, almost all of my best friends in science are academics. There’s a creativity and an ability to work on things that I probably would, in many cases, never have been able to work on at a biotech because the timelines of fruition were too long.

Is there anything else you want to add?

I worry that when a prize comes out like this, way too much attention gets put on the three of us and not on a bunch of other people whose contributions are seminal, absolutely seminal to what happens. And I don’t even mean my team and Mary’s team at the company. Yes, obviously tremendous contributions. There’s a bunch of people I could name who’ve made incredibly important, seminal discoveries related to this, without which we wouldn’t be here where we are today.

So I’m really happy that the committee recognized the discovery and its implications and now, its potential. It’s fantastic for the field, for the community overall. I think it’s great, but it leaves behind a bunch of people, and that is always a challenge or frustration for me.