In a controversial step that raises the possibility of a new kind of infertility treatment, scientists report that they have produced functional human eggs in the lab that were able to be fertilized with sperm.

The proof-of-concept study, published today in the journal Nature Communications, involves using human skin cells to generate eggs, some of which were capable of producing early-stage embryos.

None of the embryos were used to try to establish a pregnancy, and it’s unlikely that they would have developed much further in the womb. Yet the authors, from Oregon Health and Science University, say the technique could one day be used as an alternative to in vitro fertilization, or IVF.

“The obvious applications would be for older women who have run out of their own eggs or women who don’t have eggs for other reasons, such as previous cancer treatment or genetic abnormalities,” says coauthor Paula Amato, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Oregon Health and Science University School of Medicine. It could also be used to help same-sex couples have genetically related babies by creating eggs from male cells and sperm from female cells.

More people are turning to IVF to conceive, but it doesn’t always work. One of the reasons IVF can fail is because of poor egg quality, which declines with age and is a major factor in infertility. But if IVF patients could have a ready supply of eggs generated in the lab from a sample of their skin, it could vastly improve the success of IVF and allow many more people to have babies.

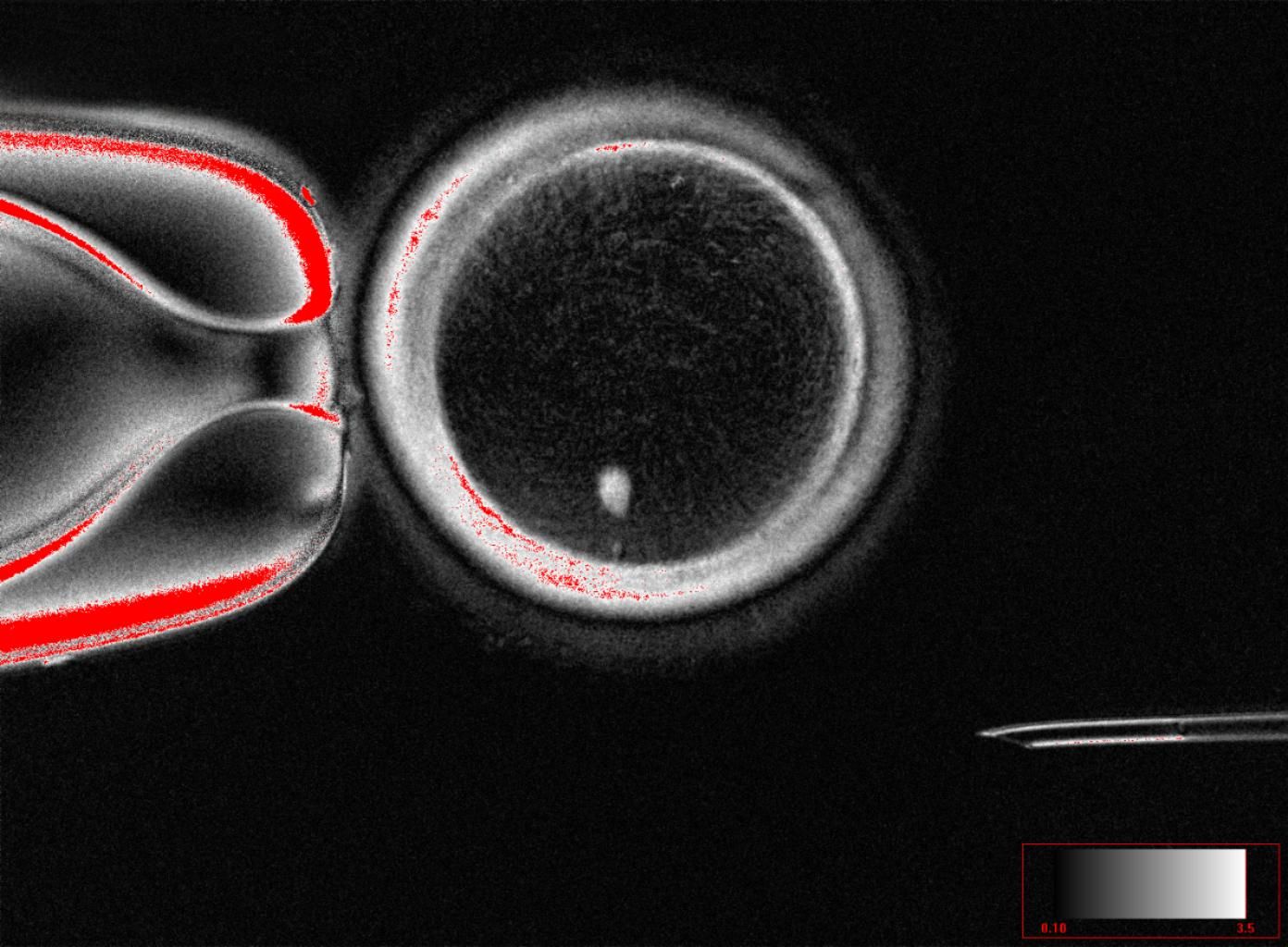

The Oregon group’s technique produced 82 eggs that were then fertilized with sperm in the lab. All of the resulting embryos had chromosomal abnormalities, and most did not make it past day three of fertilization. However, 9 percent continued developing to the blastocyst stage of development six days after fertilization, when embryos are typically transferred to an IVF patient. The authors stopped culturing the embryos at that point.

To make the eggs, researchers transplanted the nucleus of a human skin cell into a donor egg that had been stripped of its nucleus—the cell’s control center that houses its genetic material. This technique was famously used to produce Dolly the sheep, reported in 1997. Because she was a clone, Dolly’s DNA was an exact genetic replica of her mother’s.

In Dolly’s case, sperm from a father was not used. But for the Oregon team, the goal was to make embryos with genetic material from both parents. A normal sperm and egg have 23 chromosomes each, with a healthy embryo containing 46 chromosomes. But a skin cell taken from an adult already has 46 chromosomes—one set from each parent—so when its nucleus is transferred to the hollowed-out egg and combined with sperm, it ends up with an extra set of chromosomes.

An embryo with an extra full set of chromosomes cannot survive, so the team needed to figure out a way for the reconstructed eggs to shed half of their chromosomes. They stimulated the eggs with an electric pulse and applied a drug called roscovitine to mimic meiosis, or cell division, to reduce the number of chromosomes. The resulting eggs could be fertilized, but the embryos still contained chromosomal abnormalities—some had too many chromosomes, some had too few, while others had the wrong combination—and Amato says they likely would have failed in the womb.

“The biggest challenge is how to make this egg extrude half of its chromosomes—and the correct half,” Amato says. “We’re not quite there yet.” The team dubbed their technique “mitomeiosis” and is trying to better understand how chromosomes like to pair and how they segregate in order to find a way to experimentally induce those conditions.

The ability to make eggs and sperm in the lab—called in vitro gametogenesis, or IVG—has been a growing area of research in recent years.

In 2016, a group of Japanese researchers led by stem cell researcher Katsuhiko Hayashi reported that they produced healthy mouse pups after making mouse eggs entirely in a lab dish. Later, they generated mouse eggs using cells from males and as a result, created pups with two dads. Those advancements were achieved by reprogramming skin cells from adult mice into stem cells, then further coaxing them to develop into eggs and sperm.

Mitinori Saitou at Kyoto University first documented in 2018 how his team turned human blood cells into stem cells, which they then transformed into human eggs, but they were too immature to be fertilized to make embryos.

US startups Conception Biosciences, Ivy Natal, Gameto, and Ovelle Bio are all working on making eggs or sperm in a lab.

But the prospect raises significant ethical questions about how the technology should be used. In a 2017 editorial, bioethicists warned that IVG “may raise the specter of ‘embryo farming’ on a scale currently unimagined.” Conceivably, it could allow anyone at any age to have a child. And combined with advances in embryo screening, the fertility clinics of the future could use IVG to make mass numbers of embryos and then choose the ones with the most desirable qualities. Gene editing could also be used with IVG to snip out disease-causing DNA or create new traits.

Amato says it will likely take another decade of research before IVG could be deemed safe or effective enough to be tested in people. Even then, it’s unclear if the technique would be permitted in the US, since a Congressional rider forbids the Food and Drug Administration from considering clinical trials that involve genetically manipulating an embryo for the intention of creating a baby.

“Their method is very sophisticated and well-organized,” Hayashi, now a professor at the University of Osaka, says of the Oregon group’s approach. However, because of the high rate of chromosomal errors, “it is too inefficient and high risk to apply immediately to clinical application.”

Also, because their process requires donor eggs, it could limit its use as an infertility treatment. As IVF becomes more popular, the demand for donor eggs is increasing, and using them can involve wait times.

Amander Clark, a reproductive scientist and stem cell biologist at UCLA who was not involved in the work, agrees that in its current form, mitomeiosis isn’t ready to be used for fertility care. But in the meantime, the research has other uses.

“The technology of mitomeiosis is an important technical innovation and could be highly valuable to our understanding of the biology of meiosis in human eggs. Meiotic errors increase as women age. Therefore, understanding causes of meiotic errors is a critical area of research,” Clark says.