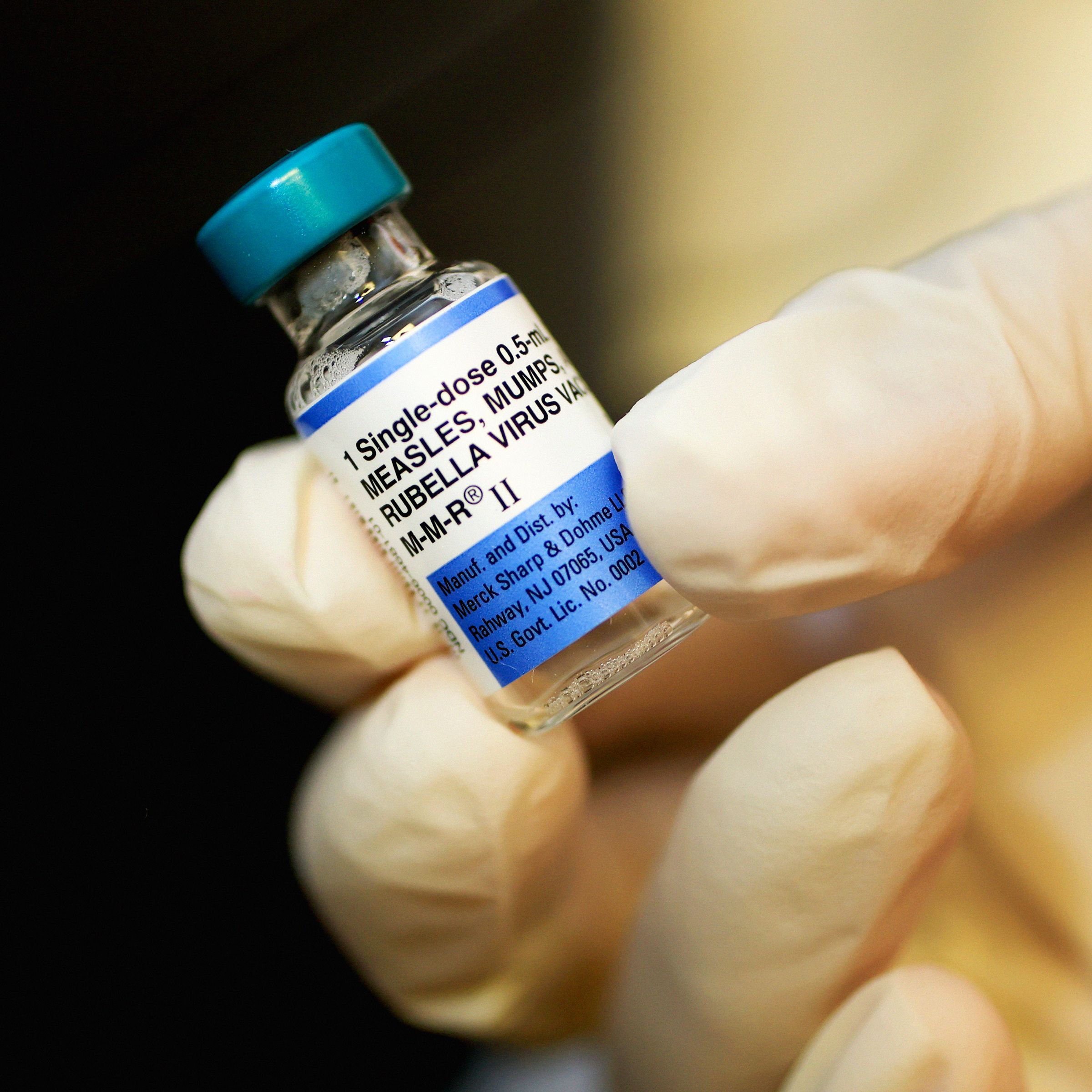

A federal vaccine advisory committee made up of members hand-picked by Health and Human Services secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. recommended in an 8-3 vote on Thursday that the combined measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella (MMRV) vaccine should not be given before age 4, citing long-known evidence that shows a slightly increased risk for febrile seizures in that age group.

Experts say that while frightening, febrile seizures—which are uncommon after vaccination—are usually short-lived and harmless, and removing the option for parents could cause a decline in immunization rates against measles, mumps, and rubella, some of the most dangerous childhood diseases.

Known as the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, or ACIP, the group provides recommendations to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on vaccine usage. These recommendations are typically adopted by CDC and have an impact on state vaccine requirements for school, insurance coverage of vaccines, and pharmacy access—something at least one member of the panel seemed to be unaware of.

Thursday’s vote is part of a new shift in vaccine policy being spearheaded by Kennedy, a longtime anti-vaccine activist. In his short time as HHS secretary, Kennedy has implemented restrictions on who can receive Covid-19 vaccines and dismissed all 17 sitting members of ACIP, replacing them with 12 new members—some of whom were installed just this week. Several of the new advisers have a history of criticizing vaccines or denouncing public health measures taken during the Covid-19 pandemic. Kennedy said a “clean sweep” of ACIP was necessary to build back public confidence in vaccine science.

On Thursday, committee members were asked to evaluate whether to recommend against the combined MMRV vaccine before age 4, as well as whether to delay the first dose of the hepatitis B vaccine until the child is at least one month old.

Currently, parents have two options for vaccinating their children against measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella, also known as chickenpox. They can choose the combined shot, known as MMRV, or two separate shots—one for MMR and another for chickenpox. About 85 percent of children get separate shots.

In the US, the hepatitis B vaccine is given in the hospital shortly after birth, because the virus can be transmitted to children during delivery. A serious liver infection, hepatitis B can lead to cirrhosis and cancer. Each year in the US, an estimated 25,000 infants are born to women diagnosed with the hepatitis B virus. Without vaccination, up to 90 percent of them would develop chronic infections. The World Health Organization advises a universal birth dose of the hepatitis B vaccine.

The topics of discussion at Tuesday’s meeting were not based on new data or evidence, and in fact, two ACIP members, Joseph Hibbeln and Cody Meissner, as well as several representatives from professional medical organizations who were in attendance, questioned why these changes were up for consideration.

Robert Malone, one of the more controversial new ACIP members, offered an explanation: “It’s clear that a significant population of the United States has significant concerns about vaccine policy and about vaccine mandates.” Malone is a former mRNA researcher who rose to prominence during the Covid-19 pandemic by spreading falsehoods about the disease and the vaccines; he abstained from Thursday’s vote because he previously served as an expert witness in a lawsuit over the mumps vaccine.

Committee members heard hours of data presentations on Thursday from CDC scientists about the well-established safety and efficacy of the hepatitis B and MMRV vaccines.

Ultimately, the vote to remove the recommendation for the combined shot for children under 4 was based on long-acknowledged evidence that the MMRV vaccine is associated with a higher risk for fever and febrile seizures five to 12 days after the first dose among children aged 12 to 23 months. A febrile seizure is a temporary convulsion caused by high fever and can happen after a vaccine or natural infection. According to the CDC, approximately one febrile seizure occurs for every 2,300 to 2,600 MMRV vaccine doses.

John Su, acting director of the Immunization Safety Office at the CDC, said during the meeting that ACIP chair Martin Kulldorff, a biostatistician and professor at Harvard Medical School until he was dismissed in 2024, requested a presentation on the MMRV vaccine and febrile seizures. (Kulldorff, one of the authors of the so-called Great Barrington Declaration that recommended isolating the particularly vulnerable and letting Covid-19 rip through the rest of the population, has claimed he was fired for refusing to receive the Covid-19 vaccine.)

The risk has been acknowledged for years, and the CDC recommends that health care providers speak with parents about the choice between the combined MMRV vaccine and separate ones.

“There’s a small increased risk for febrile seizures after the first dose of MMR and MMRV vaccines. The risk is slightly higher with MMRV combination vaccine after the first dose,” Su explained during his presentation. “Studies have not shown an increased risk for febrile seizures after the varicella vaccine.”

There is no increased risk of febrile seizures after vaccination with MMRV vaccine in children aged 4 through 6 years, when the second dose is given.

Meissner, one of the three dissenting votes and a professor of pediatrics at Dartmouth College, said the conversation was like “deju vu” to him because ACIP previously took up the issue in 2008, when preliminary data on the increased risk of febrile seizures began to emerge. The MMRV vaccine was licensed in the US in 2005.

He argued that recommending against the combined MMRV vaccine for children under 4 removes a degree of parental freedom. “What we’re saying is we don’t trust parents to make a decision. Some parents don’t want to administer two doses of a vaccine if they can receive one and get the same degree of coverage,” Meissner said. “If a parent wants to get a single dose, why are we taking away that option?

Hibbeln, a psychiatrist and neuroscientist who was previously a section chief at the National Institutes of Health and also voted no, expressed concerns that removing an option to get vaccinated against measles, mumps, and rubella could further drive down already declining childhood vaccination rates. “I think we have to have a darn good reason as to why we’re making that change,” he said.

Medical experts who spoke to WIRED were similarly confused about the new recommendation.

“While it is common for pediatricians to administer the MMR and varicella separately for dose one, there is not a reason to change the guidance that still allows a choice for parents or caregivers who prefer the combined vaccine after a discussion of the risks,” says Melissa Stockwell, a pediatrician and professor of population and family health at Columbia University.

Ari Brown, a pediatrician in Texas and a spokesperson for the American Academy of Pediatrics, which opted to not send a representative to Thursday’s meeting, says that while febrile seizures can be scary for parents, they are benign and relatively common in young children when they have a rising fever. Febrile seizures are not epilepsy or a seizure disorder.

“The slightly higher incidence in the combination vaccine should not be a reason to remove access to it. Overstating the risk undermines trust in vaccines,” she says.

Despite recommending against giving the MMRV vaccine to children under 4, the advisory committee voted 8 to 1, with one member abstaining, to maintain coverage of the vaccine as part of the Vaccines for Children program, a federal program that provides free vaccines to low-income children and those without insurance. But the committee’s recommendation could still affect private insurance coverage and pharmacy access to the MMRV vaccine.

On Friday, the CDC advisers will vote on whether to delay the hepatitis B vaccination to one month after birth and will also discuss Covid-19 vaccines.