On February 25, 2025, the Australian swimmer James Magnussen stood on the starting blocks at a swimming pool in North Carolina with a million dollars and his reputation on the line. Magnussen, a triple Olympic medalist and world champion in the 100-meter freestyle, had been retired from professional sports for six years. But he had restarted his career to join the Enhanced Games, a kind of Olympics on steroids. This is meant literally: The event, which encourages athletes to take performance-enhancing drugs, is scheduled for May 2026 in Las Vegas.

Its founder, Aron D’Souza, is a slick-talking Peter Thiel acolyte who believes throwing off the shackles of drug testing can help push humanity to the next level. Enhanced, the company behind the Games, has secured millions from Thiel, Donald Trump Jr.’s 1789 Capital, and others, and praise from the likes of Joe Rogan. But the reaction from the sporting establishment has been split between horror over the health implications and skepticism over whether the event will ever actually happen.

At the time of his February swim, Magnussen was the only athlete to have publicly said he’d be willing to compete. He’d come to the Greensboro Aquatics Center for a secret time trial. If he could beat the world record time in the 50-meter freestyle—swimming’s flagship event—he’d win a million-dollar prize from Enhanced, and D’Souza would get to prove his many doubters wrong by demonstrating that a cocktail of substances usually banned from elite sport could turn an ex-athlete into the fastest swimmer on Earth.

For four months, Magnussen had been on “the protocol”—a regimen of daily injections in the stomach and backside. No one from Enhanced would tell me what he was taking—they say they don’t want to encourage copycats—but Magnussen let it slip to the Sydney Morning Herald: testosterone to boost muscle mass and bone density, the peptides BPC-157 and thymosin to speed up recovery, and ipamorelin and CJC-1295 to increase the release of growth hormone in the body.

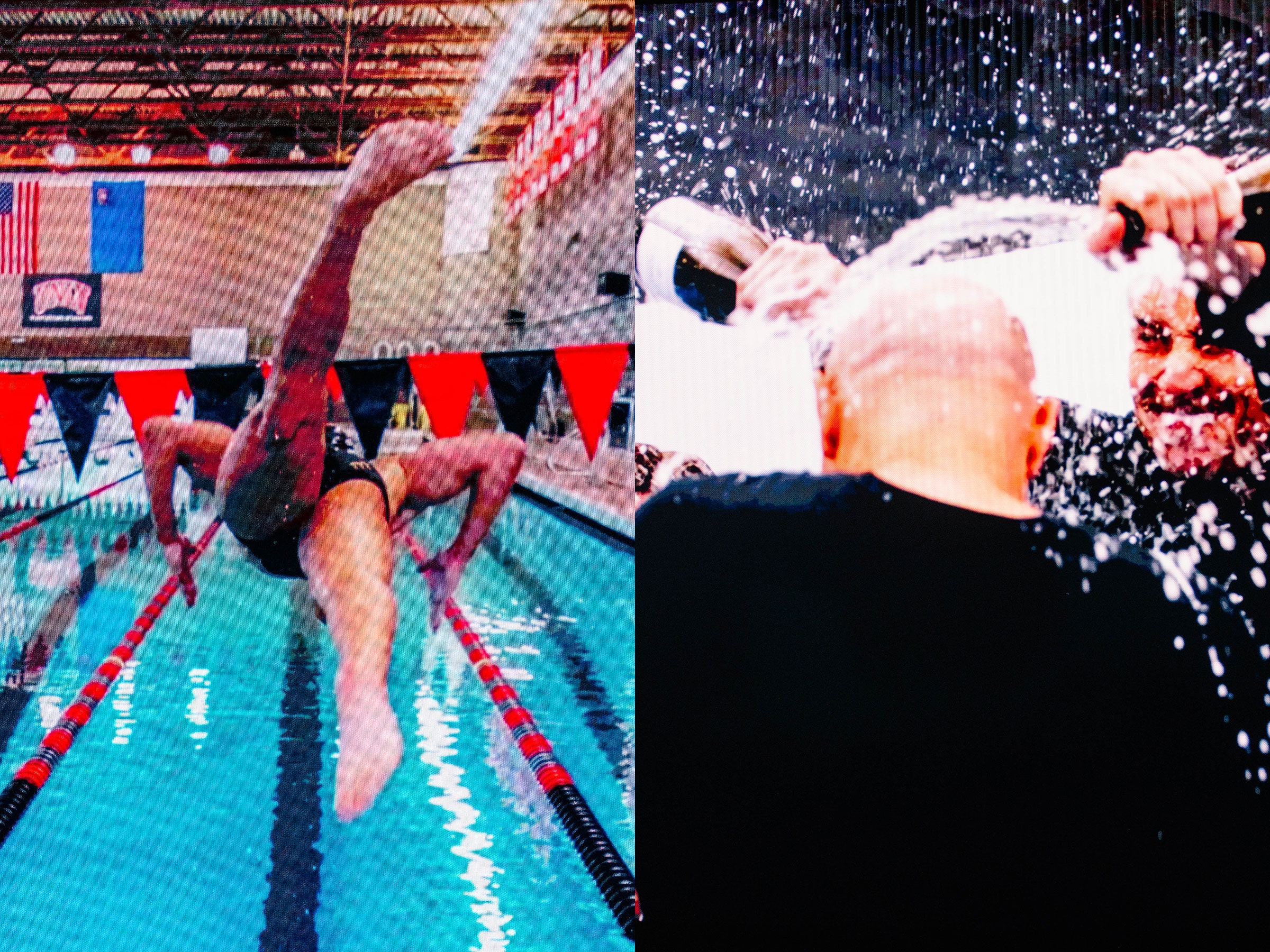

James Magnussen, the first athlete to sign up to work with Enhanced, did not have an easy time training as enhanced athlete.

Photograph: Ashley Meyers

Standing on the blocks, he looked insane—his already out-there swimmer’s physique pushed to the extreme. Veins popped on his forearms, and his shoulders were cartoonishly broad. His back muscles bulged so far out of the sides of his swimsuit that you could see them from the front. With the reflective goggles and black swimming cap, the overall effect was more alien than superhuman.

The target time was 20.91 seconds, set in 2009 by the Brazilian Cesar Cielo. But as soon as Magnussen broke the surface, you could tell something was wrong. He was sinking too low in the water. His arms raked forward, devouring the distance, but the more he strained, the more resistance he faced. He had put on 30 pounds of muscle, and his own beefed up body was working against him. The whole premise of the Enhanced Games seemed to hang in the balance. If the only elite athlete willing to come forward couldn’t get close to the world record after five months of enhancements, well, what was the point?

In 2009, D’Souza got a phone call that changed his life and set him on the path that would lead to Enhanced. The Australian was in his first week as a law student at the University of Oxford, and a friend who was close to the billionaire Peter Thiel got in touch to say they were visiting the city and to ask if D’Souza would show them around.

Befriending Thiel opened his eyes to the “extraordinary opportunities that exist in the world,” he says. These were opportunities he wanted to seize; D’Souza is “obsessed with status and power,” as his friend Sam Altman once put it. He and Thiel hit it off immediately, and a year later D’Souza went to Thiel with a plan for how, given three to five years and $10 million, Thiel could take his revenge on Gawker for outing him as gay. Improbably, this involved covertly funding legal action by the wrestler Hulk Hogan against Gawker, which had published a sex tape without Hogan’s consent. Although D’Souza is also gay, his plan to take down Gawker—which folded after Hogan won a $140 million verdict against it—was apparently not part of some righteous crusade. It was “just a way for him to make his mark,” writes Ryan Holiday in Conspiracy, a book about the trial.

After the verdict, D’Souza bounced between careers—diplomat, VC, philanthropist, fintech founder. But in the waning days of 2022, he got an idea. Every year D’Souza would spend the holidays sketching out new business plans—a subscription-based social network, a scheme to fund a poet laureate to define what it means to be Australian—but nothing had really stuck. Inspired by the ripped physiques he’d been seeing at the gym and on Instagram, D’Souza refined some thoughts for a showcase of just how far you could push human potential. He had the sense that public attitudes toward steroids were starting to shift after years of stigma following their misuse by athletes and state-sponsored doping regimes in the 1980s and 1990s.

Aron D’Souza, mastermind of the Enhanced Games.

Photograph: Ashley Meyers

It was a notion that had been percolating in D’Souza’s head for years—ever since he’d read an article in a 2004 issue of WIRED called ‘Steroids for Everyone!’ that outlined the case for an Enhanced Olympics using almost exactly the same argument that D’Souza employs today. There were other inspirations too: the “unimpressive” intellect of members of the International Olympic Committee who he met at a dinner in Oxford, and a study commissioned by the World Anti Doping Agency which surveyed athletes anonymously and found that 44 percent of them admitted to taking drugs. (This figure is one of D’Souza’s most potent weapons in interviews, but one of the authors told me that it’s likely an overestimate and that it was only ever meant to be a pilot study to assess new methods of measurement.)

He spent New Year’s Eve with Thiel, as he does most years, and told the billionaire what he’d been working on. Thiel seemed interested, so D’Souza spent the next six months developing the concept further. D’Souza and his executive assistant Thomas Dolan tried pitching to investors (including Lance Armstrong, according to the Financial Times) but got little interest. “Everyone was like, you can’t even talk about this stuff,” D’Souza says. “It was outside the Overton window.” In June 2023, D’Souza launched a website for the Enhanced Games and posted a 34-second stock-footage clip of a sprinter in the blocks, with a voice-over declaring that he was the fastest man in the world and “a proud enhanced athlete.” It presented the Games as a libertarian ideal: take whatever you want, with no testing.

D’Souza and Dolan spent £4,000 ($5,400) on paid promotion, and the clip got 9 million views in 24 hours. Enhanced had its first media coverage and its first investor—the prominent venture capitalist Balaji Srinivasan, who reached out to D’Souza via Twitter DM, and followed up a few hours later with a term sheet for the deal, also sent over Twitter DM.

A few weeks later, D’Souza hosted a Sunday lunch at his house for Thiel, who was visiting London, and a few friends in the gay VC community. “We’ve all holidayed together for years,” he told me. “It’s an extraordinarily tight group.” Also on the guest list was Christian Angermayer, a German biotech billionaire who Thiel had introduced to D’Souza on holiday in 2013. Angermayer had seen an article about Enhanced in the German press and wanted to come on board as a cofounder.

Neither Thiel, D’Souza, nor Angermayer are huge sports fans. (“We’re three gay guys,” D’Souza says.) But over roast lamb, Yorkshire pudding, and fine wine the group got to talking about human enhancement, longevity, and all the rest of it, and by the end of the meal both Angermayer and Thiel had agreed to invest. D’Souza has proved to be a savvy fundraiser. He has the valuable ability to keep a straight face while saying something obviously ridiculous—engaging with him is “like talking to a bar of soap,” one doping expert told me.

The announcement of Thiel’s and Angermayer’s investments went out at the end of January 2024 and sparked a new round of media coverage, and the fiercest criticisms yet from health experts. Those I spoke to were worried about the effect of long-term steroid use on athlete’s hearts, premature aging, and what might happen to people when they tried to come off the drugs. Others thought that an event like the Enhanced Games might cause steroid use to spread first through sport, then through society at large, and that people might end up taking larger doses or counterfeit versions of the pills that athletes are using. “There’s going to be enormous ripple effects that will certainly have destructive implications in people,” says Thomas Murray, bioethicist and author of Good Sport: Why Our Games Matter—and How Doping Undermines Them. Personally, I felt that D’Souza had fundamentally misunderstood sports. At heart, they are about limitations: not who can travel 100 meters the fastest but who can do it while staying within a set of agreed-upon rules (no drugs, no rocket boots, no giant fan blowing a tail wind behind you). And even in events like sprinting and swimming, success isn’t simply a function of adding more power. People aren’t cars. There’s a skill to swimming quickly that goes beyond the strength of your muscles. And the drugs aren’t magic—even if you can take half a second off your 100-meter sprint time with steroids (and that’s a generous estimate), to break Usain Bolt’s record you need to find one of the handful of people who can already run 100 meters in less than 10 seconds and then convince them to risk their reputation, their earning potential, and maybe even their health.

Still image from video shown at Enhanced Games promotional event.

Photograph: Ashley Meyers

Which raises a question: Why would even one athlete agree to this? In February 2024, Magnussen was driving home from a pickleball game when he got a call from the Hello Sport podcast; the hosts wanted to ask him about the Enhanced Games. He had a comfortable life in Australia: swimming at Bondi Beach every day and working as a commentator. But he missed the thrill of competition. “I love the simplicity of being an athlete,” he says. He made a flippant comment that would change his life and help usher the Games into being. “If they put up a million dollars for the 50-freestyle world record, I’ll come on board as their first athlete,” Magnussen told the podcast hosts. “I’ll juice to the gills and break the record within six months.”

A month after that, I met D’Souza at a plush coworking space in West London where Enhanced had set up a small office. Looking at the website back then, it was hard to take the idea seriously. D’Souza had co-opted the language of the LGBTQ community for his venture—the site talked about “coming out” as enhanced. There was a section devoted to covertly editing Wikipedia articles to, for instance, change the word “cheated” in an article about an athlete caught doping to “fought for science and bodily sovereignty.” On the official Enhanced Games Discord channel, which was mainly populated by bodybuilders sharing before and after pictures, I found a zip file called “The Arsenal” which was full of memes bashing the International Olympic Committee, the details of which are actually too cringe to describe.

But behind the scenes, things were starting to change. Angermayer had put his own people into senior roles, drafting in Mike Oakes from his Apeiron Investment Group to work on communications and Max Martin—a square-jawed twentysomething whose enthusiasm about his own enhancement program almost had me reaching for a syringe—to oversee the execution of the Games. More sensible hires followed: sports scientist Dan Turner to head up a scientific commission that would help advise athletes, former Team USA chief Rick Adams to handle the logistics of the event itself, Tim Phelan from Nike to run athlete relations. Magnussen had officially come on board as Enhanced’s first athlete—they’d pay him a monthly salary. The mission changed, too, to become more about getting the public to embrace steroids, “the Enhanced Age,” superhumanity for everyone. There was also unrest: Early on, Angermayer had brought in physician Michael Sagner to sit on an independent medical commission that would ensure athlete safety. Sagner, a longevity and aging expert who operates a high-end clinic just off London’s Harley Street, became incensed by some of D’Souza’s public statements. “Without asking anybody, he was just going bananas with these press releases,” Sagner says. “And then it became even more outrageous when there was something else added to the website—that it’s even better without testing, and anything goes.” He has stuck around—for now.

The Paris Olympics came and went with barely a peep from Enhanced. The first Enhanced Games had been slated for the end of 2024, but the open trials D’Souza had told me about the first time we met never materialized. Magnussen, still their only athlete, was getting restless.

In October 2024, Magnussen flew from Sydney to Los Angeles. He had presented Enhanced with a plan: With eight weeks to dope and train, he could try to break the world record as a way to showcase the potential of the Games before the first official event. His first challenge had been finding the drugs. A few companies had contacted him, and Enhanced had put him in touch with some members of its medical commission, but it wasn’t the kind of thing that was easy to get advice on.

The next hurdle was finding somewhere to swim. Elite-level pools and coaches in Australia can only work with drug-tested athletes, so Magnussen reached out to Brett Hawke, a former Australian Olympian turned coach who had worked at Auburn University in Alabama for many years and was now coaching a club team in Irvine, California.

Hawke had coached the two previous fastest swimmers in history—Frédérick Bousquet in the years after his 21.04 in 2004, and Cesar Cielo’s 20.91 in 2009, which was the target Magnussen would be trying to beat. Both these swims were in the supersuit era, when swimmers wore full-body polyurethane suits that made them more buoyant, before these were banned at the start of 2010. (Both swimmers also failed drug tests during their careers). Magnussen and Hawke had spoken about the Enhanced Games on Hawke’s podcast a few weeks prior, and Magnussen figured California might be an easier place for him to train in anonymity.

At the height of his Olympic career, Magnussen had worked with a full team around him: biomechanicists, sports scientists, strength and conditioning coaches, physiotherapists, assistants. He had underwater cameras to check his form. The temperature of the water was always perfect. Irvine was different. It turned out that the pool manager at the club where Hawke normally worked didn’t want Magnussen training there either. So they ended up doing the majority of the preparation for the world record attempt at the 25-yard swimming pool in Hawke’s apartment complex—the one open to all residents. There were no lane markings and no blocks to dive from. There were no splash-over areas for the water to go into, so Magnussen was constantly fighting his own turbulence. “We would get a crowd sometimes. People would walk past and stare in amazement and sit and watch,” Hawke says. The only saving grace was the weather: a cold wet winter by California standards meant that they never had to share the pool with the other residents, although they did sometimes have to shoo away some ducks. “The whole process was bizarre to me,” Magnussen says.

James Magnussen, who burst through multiple swimsuits in his attempt to set a new world record.

Photograph: Ashley Meyers

He started his regimen of daily injections in mid-October, and his body soon started to change. In hindsight, he thinks he is a “super responder” to performance enhancements. “My strength was through the roof,” he says. “I was squatting 250 kilos, which I would say is at least 20 percent stronger than any other swimmer in history. It was insane.” Every few weeks, he would drive to a clinic in Los Angeles for a battery of blood tests and heart checks. Mostly he just trained—twice a day, every day for the first seven weeks in the US. But while the drugs helped his muscles bounce back quicker, the intense workload left no time for his central nervous system to recover. He was burning out.

In December, just when he should have been nearing his physical peak for the record attempt, he got a toothache, and his face “swelled up like a balloon.” He spent Christmas Day in the hospital, having an abscess drained and a root canal operation. The attempt had been pushed back from December to February, and for Magnussen what was meant to be an eight week stint away from friends and family became five months. He spent New Year’s alone in an Airbnb, thousands of miles from home.

While Magnussen and Hawke toiled among the ducks and deck chairs in California, the Enhanced Games were inching closer to reality. More athletes were expressing an interest, D’Souza said—although none of them had yet been willing to stick their head above the parapet like Magnussen. Estimates ranged depending on who you asked: Some at Enhanced told me the number of interested parties was in the hundreds; Sagner put it at 35.

D’Souza says Enhanced was talking to “every major sports broadcaster” about screening the event, but he had his eye on social media virality. Angermayer drummed up interest from investors, while Max Martin and Rick Adams toured the world in search of potential host cities. But by the middle of 2024, they’d decided to wait and see who won the US presidential election. The Biden administration had been actively hostile to the idea of Enhanced. A Trump win opened up all sorts of interesting possibilities.

Enhanced began finalizing a deal to host the Games in Las Vegas not long after the election. “A hundred percent the reason they’re happening in the US is because Trump won,” says Angermayer. A few months later, he secured investment from 1789 Capital, Donald Trump Jr.’s investment firm, and Enhanced would find itself ideally positioned to align itself with RFK Jr.’s crusade to “Make America Healthy Again.” (“He takes enhancements himself,” D’Souza says of Kennedy. “He is very pro–human enhancement.”) Enhanced started making plans to move its headquarters from London to New York.

In December 2024, D’Souza held a conference in Oxford on human enhancement. Speakers included the geneticist George Church, best known for trying to bring back the woolly mammoth, and Bryan Johnson, best known for plowing his personal fortune into increasingly creepy attempts to make himself younger. At the end, they signed the “First Declaration on Human Enhancement”—a document setting out the tenets that these “pioneers” agreed to follow. The 39 signatories are a strange mix: age-obsessed millionaires, longevity doctors, Enhanced staff members, interested college students, and a bodybuilding influencer called Mr. Vigorous Steve.

But the most interesting thing was the shift in tone. Angermayer’s influence had made itself felt. Take Article 2d of the declaration: In competitions, organisers shall establish rigorous safety protocols, scientific testing and medical supervision to ensure that all enhancements are used responsibly.

This is a long way from the libertarian free-for-all that D’Souza had first proposed, and in fact, the more the Games evolved, the more they started to resemble the Olympics. “Obviously, as soon as you want to be taken seriously as a contender on the world stage … you can’t have footage of athletes dropping dead,” says Ask Vest Christiansen, a doping researcher who was at the conference in Oxford but did not sign the declaration.

There was much trial-and-error with training the “enhanced” athletes.

Photograph: Ashley Meyers

Athletes who wanted to compete in the Games would be limited to legal drugs that were approved in the country where they reside and prescribed by a doctor, although several of the drugs Magnussen confessed to taking do not appear to have regulatory approval in either Australia or the US. (Enhanced said it couldn’t comment on the “specific substances” Magnussen has taken but emphasized that he “underwent and successfully passed all of Enhanced’s required medical screenings and safety checks at every stage of the process.”) Athletes would have regular blood tests and heart and brain scans, and if the doctors on the independent medical commission were concerned, those athletes would be barred from competing at the Enhanced Games.

Far from throwing off the shackles of the World Anti Doping Agency, it seemed as if Enhanced had simply re-created it, with a slightly different red line. The great irony of the Enhanced Games is that athletes who take part are likely to be tested much more often than they would have been had they stayed in clean competition. But by January 2025, the Enhanced Games had a venue, funding, and a friendly political environment. All they needed now was some proof that the drugs would actually make a difference.

After Magnussen recovered from his root canal surgery, he and Hawke tried to counteract some of the effects the enhancement program was having on his body shape. Swimming is a trade-off between power and weight: the heavier you are, the more you sink into the water and the more resistance you face when you’re trying to propel yourself forward. He went on a diet plan to try to lose some of the weight he was putting on. Although Magnussen’s athlete brain would never let him admit it, it was becoming clear to both him and Hawke that they were running out of time for him to get into world-record-breaking form.

In the meantime, Hawke got a call from Tim Phelan, Enhanced’s VP of athlete relations. They had received an email from another athlete who wanted to sign up for the Games—a 31-year-old Greek-Bulgarian swimmer called Kristian Gkolomeev, who had finished fifth in the 50-meter freestyle at the Paris Olympics. (Enhanced says some non-swimmers have signed up too but has yet to name any.) Gkolomeev’s ambition had always been to win a medal, but after Paris he felt despondent—he had missed out by less than three-tenths of a second for the second Olympics in a row.

Kristian Gkolomeev, another swimmer attracted to the million-dollar payday, at Enhanced Games event.

Photograph: Ashley Meyers

Throughout his career, Gkolomeev would bemoan how difficult it was to make a living as a professional swimmer. It was why his father Tsvetan—who swam for Bulgaria at the 1980 and 1988 Olympics—had moved the family to Greece in search of stable work when Kristian was 2. (Tsvetan died of skin cancer in 2010). Gkolomeev had his own young family now, and as he looked at the four years leading up to the next Olympics he wondered how he was going to make it work. Financially, mentally, emotionally, he was done. The million-dollar prize on offer for breaking a world record offered a tempting way out. “One successful year in the Enhanced Games and I could make as much as I would have made in almost 10 careers,” he says.

In early December 2024, Gkolomeev rented an Airbnb and moved his family from Houston to join Hawke in California, ostensibly to serve as a training partner for Magnussen. But a couple of weeks later, Hawke got another phone call. Gkolomeev was going to start an enhancement protocol—and he was going to try to break the world record too. “That’s when all hell broke loose,” says Hawke.

Magnussen had moved his whole life to America for the record attempt and was “dead against” another swimmer muscling in on his turf, according to Hawke. “I wasn’t thrilled about the prospect of having to share resources,” says Magnussen. “But it’s not just about me and my attempt. To prove this concept of the Games, someone needed to break that world record.” Eventually they reached a compromise. Magnussen would get the first crack at the record attempt and the million dollars in February, then Gkolomeev would come back a few months later for his own attempt.

Hawke’s job became as much about managing their egos as making them faster—he had to keep them separated when they were doing speed work so that they never got a direct comparison of their times. “Kristian’s progression was a lot faster,” Hawke says. “That created a little bit of tension.”

Within a few weeks, Gkolomeev was swimming faster than Magnussen. Within a month, he was as fast as he’d been in Paris. In early February, Gkolomeev started his enhancement program. Like everyone at Enhanced, he was cagey about exactly what substances he was using, but it’s clear that he took a very different approach than Magnussen. “I can tell you that I microdosed, like baby doses,” Gkolomeev says. “I could feel it within the first two weeks. I started feeling better—healthier, the energy levels, the confidence that I got.” Magnussen’s extra muscle was weighing him down—they didn’t want the same thing to happen to Gkolomeev.

A camera crew was following the swimmers as they tried to set new world records.

Photograph: Ashley Meyers

In the last week of February, Gkolomeev, Magnussen, and Hawke flew to North Carolina, where they were joined by a team from Enhanced and the documentary crew that would film the record attempt.

The Enhanced team had been scouring the country looking for 2009-era supersuits for Magnussen to wear—contacting former swimmers, paying thousands to buy their old gear and have it flown to Greensboro. They managed to find four: two for Magnussen, two for Gkolomeev. But Magnussen had put on so much muscle that he physically couldn’t fit into the suit. The night before his first attempt at the record he tried one on and it ripped. Then the second suit ripped as well.

That night, there was a furious discussion in Hawke’s room at the Marriott in Greensboro between Magnussen, Hawke, and Max Martin from Enhanced. Magnussen wanted the third supersuit—the one that had been promised to Gkolomeev. Hawke says the Greek was in his room downstairs, texting Hawke: “I’m not giving him my suit, I need it.” He’d done 21.45—just a hundredth below his personal best—in a time trial that morning and was within half a second of the world record in a newer, less buoyant supersuit. He felt like he could break the record.

“Kristian was a little pissed off at that stage,” Hawke says. He thinks the tension between the two men might go some way to explaining what happened next.

When he touched the wall on his final attempt in Greensboro on February 25, Magnussen’s time was 22.73 seconds—almost two seconds off Cielo’s world record and 1.2 seconds slower than his own clean personal best. He’d failed again, and the Enhanced team would have to regroup. They didn’t have their record.

Magnussen was getting a massage in a room to the side of the pool when he heard Gkolomeev hit the water. Hardly anyone was watching—most of the film crew had taken a break, so only Hawke, Martin, and the official timekeepers were actually poolside to witness what happened next. The stakes seemed low, although the million was still up for grabs if either swimmer could go under 20.91 seconds. Gkolomeev had done two warm-up starts and slipped off the blocks both times, falling flat on his face, and he was planning to spend another couple of months on the enhancement protocol before returning to Greensboro in April for his own crack at the record.

But his third start was perfect. He slid into the water, and three powerful dolphin kicks set him on his way. He felt good—strong, relaxed, in flow. Magnussen could see a slice of the pool through the open door of the massage room, and when he saw him go past he knew he was going quicker than before. Hawke was jogging alongside the pool with a stopwatch to track the split times, and at the 35-meter mark he realized what was about to happen. Gkolomeev touched the wall and turned to check his time on the big screen in disbelief—20.89 seconds, a new world record. Mouth agape, hands raised to his black swimming cap in genuine shock. At the other end of the pool, Martin jumped into the water in celebration. “I felt like a Labrador who just couldn’t help himself,” he says. Hawke sat with his head in his hands, as if he couldn’t quite believe what they had just done. “It was a beautiful day,” Martin says. “Brett was crying. One of the officials was crying.”

Gkolomeev phoned his wife to tell her they were millionaires. The giant check presentation had to wait, though—the organizers had arranged one, but it had been made out to James Magnussen, so they returned the next day to stage some footage for the documentary and some slow-motion shots of them spraying champagne over each other. There was always one eye on the optics—and news of the record was kept a closely guarded secret, for now.

Seven weeks later, Gkolomeev returned to North Carolina to break another world record—for the fastest time in “jammers,” the skintight shorts that elite swimmers have worn since the supersuits were banned in 2010. But he found this one a lot harder. He had been on the enhancement regime for longer, and although he hadn’t put on as much weight as Magnussen, he had to adjust his technique to compensate. In the end, it took Gkolomeev five attempts to go one-hundredth of a second under Caeleb Dressel’s 2019 time of 21.04.

The fact that Gkolomeev seemed to get slower the longer he spent on the protocol made me wonder if he could have broken the record anyway, without the enhancements. “I would like to think yes,” says Hawke, his coach. Gkolomeev agrees—but says it would have taken longer, maybe six months of training. Magnussen, perhaps unsurprisingly, gives credit to the drugs. “If you watch his 50-meter freestyle race in Paris, at the 15-meter mark he was eighth,” he says. “He was last because he didn’t quite have that explosive strength and power that you get on the performance enhancement protocol. I think that gave him that last 1 percent—that last cherry on top to break the world record.”

In May, Enhanced held what it was referring to internally as an “Apple-style launch event” at Resorts World, a sprawling hotel and casino complex in Las Vegas, where it would announce the date and venue of the first Enhanced Games. It was a day many of the doubters had thought would never come. If you’d asked me six months ago I would have agreed. But the changing political climate and Gkolomeev’s record-breaking feats had changed what seemed possible.

The Vegas crowd during the Enhanced Games event.

Ashley Marie Myers

In keeping with D’Souza’s digital-first approach, the presentation was being streamed on YouTube, but there were about a hundred people gathered inside Zouk nightclub, where the VIPs seemed to outnumber the regular guests by about 4 to 1. There were burly men in suits that somehow managed to show off their arm muscles, several of whom turned out to be longevity doctors. I met Zoltan Istvan, a transhumanist who is running for governor of California. Enhanced staff—almost exclusively fit, young, and possibly enhanced men—buzzed around in branded black T-shirts. Peter Thiel’s husband, Matt Danzeisen, was there with a delegation from Thiel Capital and a security detail so discreet that I didn’t even notice they were there until someone told me afterward.

After a heavy-handed introduction—Greek statues crumbling, a solemn voice-over saying things like “we dream beyond what we were allowed to dream”—D’Souza took to the stage. He looked unusually nervous. The first Enhanced Games, he announced, would take place at Resorts World in Las Vegas on Memorial Day weekend in May 2026. If that was a bit anticlimactic—we were already sitting there, after all—what came next shocked the crowd. Angermayer got the honor of doing the Steve Jobs line—“one more thing”—as he introduced a clip of Gkolomeev breaking the 50-meter freestyle world record. There was a stunned silence in the room, followed by a round of applause. A guy near the front with a wrestler’s physique and visible forehead veins rose to his feet in a standing ovation.

The Games had morphed from a libertarian Olympics into something smaller, safer—an exhibition with a few thousand in-person spectators. There will be a six-lane athletics track and a weightlifting arena. Gkolomeev and Magnussen will compete in the pool—with a more subtle enhancement program and the right suit, the Australian is sure he can break the record.

But maybe the event was never the point. All through my reporting I’d been struggling to understand what was in it for the investors—why billionaires with no interest in sport were so interested in disrupting it. Toward the end of the presentation in Vegas, it all clicked into place when D’Souza announced the launch of Enhanced Performance Products—a new line of supplements inspired by the ones athletes will be taking to prepare for the Games. This pill helped me run 100 meters in nine seconds, and now you can buy it too. The model isn’t the Olympics or the World Cup. It’s Red Bull.

“They buy sporting assets to sell an energy drink,” D’Souza told me. “That energy drink is 90 percent gross margin. They don’t do the bottling or manufacturing, that’s all done by outsourced service providers. And Red Bull is a multibillion-dollar company owned by two families. And so our business model is very similar.”

When I met D’Souza in his suite a few hours after the launch he was in a triumphant mood. He told me at least 20 new athletes had expressed interest, and “dozens” of people had signed up for the supplement line. He had received text messages from more than one royal. No matter that the livestream had, at the time of this reporting, a mere 4,000 views. The press had amplified that a thousand-fold. The sporting establishment had spent a year trying to ignore Enhanced, but in the following days USA Swimming sent a letter to athletes warning them against competing, and World Aquatics said athletes could still be banned for joining the Enhanced Games even if they competed clean. (Enhanced has always said drugs are optional for competing in the Games.) The World Anti Doping Agency is calling on the US authorities to shut down the Games. If it was all just marketing, he’d done a very good job.

D’Souza gestured out at Las Vegas—the hollow facade of the Sphere playing ads on an endless loop, the city conjured out of the desert, the parking lot soon to be transformed into the cradle of superhumanity. “In a year’s time we’re going to look out of that window and say wow—we built a track, we built a pool, we built a weightlifting arena, and we smashed a whole bunch of world records, and we did it safely and the world watched,” he said. In his mind, this moment was on par with the JFK speech that launched the space race—something to tell my grandchildren about. The dawn of the Enhanced Age.

This article appears in the September issue. Subscribe now.

Let us know what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor at mail@wired.com.