All products featured on WIRED are independently selected by our editors. However, we may receive compensation from retailers and/or from purchases of products through these links.

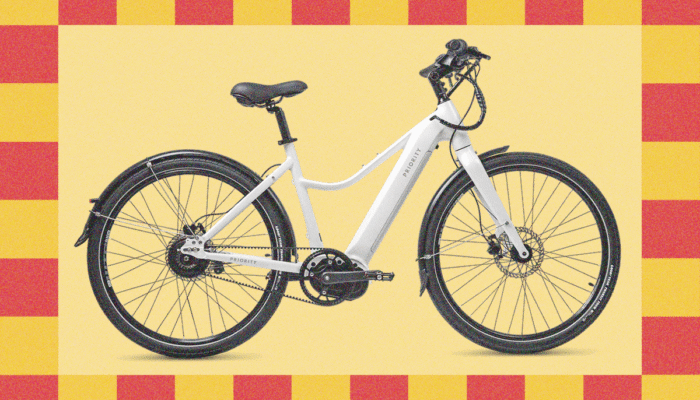

An ebike library is exactly what it sounds like: a place where people can borrow electric bikes for free for, in some instances, as long as a week. And lately, thanks to the growing popularity of ebikes, these lending libraries have begun to sprout up around America.

According to some experts, ebike libraries serve two purposes: to expose potential buyers to the advantages of ebikes through a real-world test ride and to provide access to free transportation in or near lower-income communities.

There are approximately 50 ebike libraries around the US, a number that has nearly doubled since 2022. Many of them are housed in local bike shops, though some are connected to traditional book-lending libraries.

In many ways, ebikes have made cycling more accessible than ever. Their electric motors flatten hilly areas, where biking can be strenuous, allowing anyone who knows how to ride a bike to climb almost any hill. They enable easier commutes and around-town errands more than traditional bikes. They lighten the load of towing kids around, whether to school or simply for recreation. They ease the weight of a bike loaded with two or three or four bags of groceries.

Because of this, ebikes have exploded in popularity over the past few years. According to a 2023 study published by the US Department of Energy, ebike sales in the US grew fourfold from 2018 to 2022, from 287,000 to over 1.1 million. By 2024, that number doubled, with around 2.05 million electric bikes sold in America.

On a recent trip to New York City—where I visit often and almost exclusively travel via the city’s CitiBike bikeshare program—though traditional CitiBikes were plentiful, the models with electric pedal-assist motors were almost always all spoken for.

Even though ebikes have gotten cheaper in recent years, the price remains a major barrier of entry. The cheapest reliable ebike you can find is the Aventon Soltera.2, which will set you back around $1,100. If you want something with additional seating to haul your children around, you’re looking at the Lectric XPedition 2.0, which costs about $1,400. Prices can easily climb into the mid-five-figure range, while some high-end ebikes retail in excess of $10,000.

Where ebikes have given people more options when it comes to pedal-powered transportation, ebike libraries have made access more equitable.

The scope, scale, and function of these libraries vary from city to city. For example, Montpelier, Vermont’s library loans bikes by the week, from Saturday to Saturday. Farther south, in the Vermont town of Brattleboro, residents can borrow one of three ebikes for six days, checking them out on Fridays and returning them the following Wednesdays, allowing the library to charge the battery and make any necessary repairs on Thursdays. In California, residents of the city of Elk Grove can borrow ebikes from the lending library for as long as three weeks.

One trend that seems to be growing in newer libraries is the idea of short-term loans, which can better facilitate usage for running errands or even taking a recreational spin around town.

Madison, Wisconsin’s ebike library has been one of the most robust in America over the past few years. Known as the Community Pass Program, it offers free usage of the city’s Madison BCycle ebike-sharing program through the city’s libraries. Unlike CitiBike, Washington, DC’s Capital Bikeshare, or Chicago’s Divvy, all of which require a credit-card-linked account for use, a Bcycle can be unlocked with a fob obtained for free at any of the city’s nine library branches. All you need is a Madison library card. The fobs can be checked out for as long as a week. (The program is currently on hold through the summer while it undergoes program updates.)

While Madison’s library—and therefore its residents’ access to BCycles—spans much of the city, several cities are strategically placing their ebike libraries in or near lower-income communities, offering a free means of transportation to people who might struggle otherwise with a bikeshare program or who are less likely to own a car.

“It costs a minimum of $8,000 a year to own and operate a car in our country,” says Arleigh Greenwald, a former bike shop owner and YouTube influencer focused on ebike travel. “And if it’s not required to own a car in order to live where you live, you’ve now made a person’s annual cost of living so much less. If you require someone to drive to get to an affordable housing unit, it’s no longer affordable.”

Meanwhile, the town of Carlisle, Pennsylvania, has a lending library connected to a progressive halfway house called Tomorrow’s Neighbors. The library provides any of its 20 ebikes for its temporary residents who might be commuting to jobs, looking for work, or simply in need of exercise or recreation.

“In that case, not only is it addressing a transportation need but it’s helping reduce recidivism,” says Michael Galligano, CEO of Shared Mobility, national nonprofit based in Buffalo, New York, that aims to make transportation easier and more equitable.

Smaller cities and towns simply may not have the funds, the initiative, or the interest to install a citywide network of bike-sharing options.

“Having free access to ebikes is not a hard sell,” Galligano says. “But where the rubber meets the pavement is the community helping to organize these programs”

Some places have welcomed dock-free bikeshare companies such as Lime, but those cost a fee to unlock then the user is charged each minute they’re riding

In Chapel Hill, North Carolina, a fleet of 100 Tar Heel Bikes—which are provided by Lime competitor Bird—can be found around the town and throughout the campus at UNC–Chapel Hill. However, those cost $1 to unlock plus 29 cents each minute they’re ridden.

On the other hand, the town of Chapel Hill recently announced a free ebike library, which is housed in a pair of local bike shops and is operated by town officials. According to the official announcement, the program was funded through a $129,010 grant from the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Block Grant, along with an additional $50,000 from the American Rescue Plan Act.

Through that library, town residents aged 18 and older can borrow a standard ebike, a cargo ebike, or an electric tricycle for as little as a few hours and as long as a week. Users are also provided with a combination lock, a charging cable, and a helmet.

“Most of them have been two- to three-day rentals,” says Brian Van Cleve, a longtime staffer at Trek Chapel Hill, which, along with local shop The Bicycle Chain, is participating in the library. “People who are interested in buying an ebike want more than a 20-minute test ride. But we’ve had someone here who needed a bike because they were working Doordash.”

As ebikes continue to grow in popularity, the appetite for ebike libraries is expanding in concert. Galligano pointed out that Shared Mobility fields calls every week from municipalities around the US, all interested in starting an ebike library.

“These programs are launching all over the place, because cities see a need for equitable and affordable transportation,” Galligano says. “And yeah, there’s an environmental impact, there’s a health impact, yeah there’s a transportation impact. But there’s a mental impact, too. You have to see people’s faces sometimes. It’s the first time they’ve been on a bike in years, and you can see how happy they are just being able to bike.”