Anthropic announced two new models, Claude 4 Opus and Claude Sonnet 4, during its first developer conference in San Francisco on Thursday. The pair will be immediately available to paying Claude subscribers.

The new models, which jump the naming convention from 3.7 straight to 4, have a number of strengths, including their ability to reason, plan, and remember the context of conversations over extended periods of time, the company says. Claude 4 Opus is also even better at playing Pokémon than its predecessor.

“It was able to work agentically on Pokémon for 24 hours,” says Anthropic’s chief product officer Mike Krieger in an interview with WIRED. Previously, the longest the model could play was just 45 minutes, a company spokesperson added.

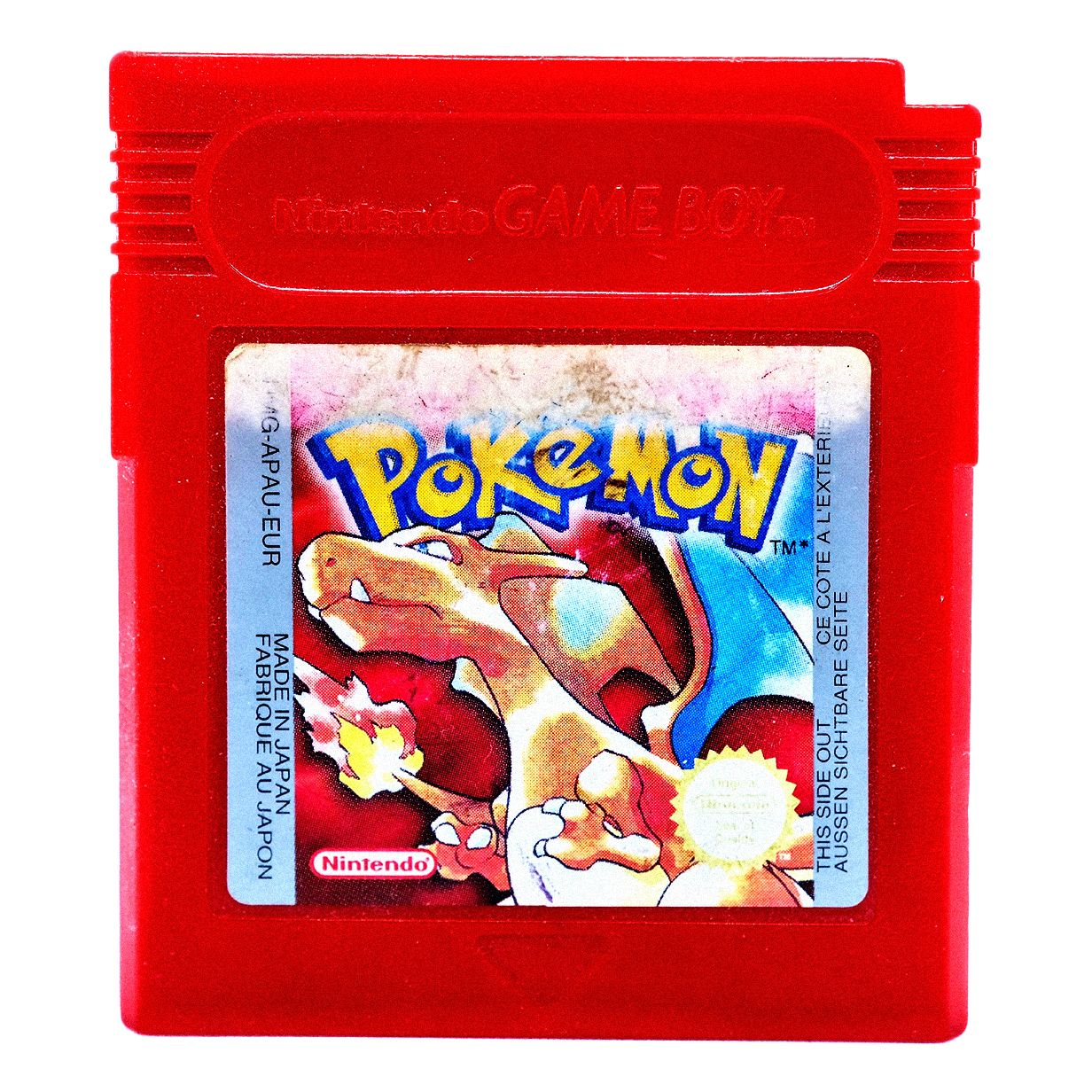

A few months ago, Anthropic launched a Twitch stream called “Claude Plays Pokémon” which showcases Claude 3.7 Sonnet’s abilities at Pokémon Red live. The demo is meant to show how Claude is able to analyze the game and make decisions step by step, with minimal direction.

The lead behind the Pokémon research is David Hershey, a member of the technical staff at Anthropic. In an interview with WIRED, Hershey says he chose Pokémon Red because it’s “a simple playground,” meaning the game is turn-based and doesn’t require real time reactions, which Anthropic’s current models struggle with. It was also the first video game he ever played, on the original Game Boy, after getting it for Christmas in 1997. “It has a pretty special place in my heart,” Hershey says.

Hershey’s overarching goal with this research was to study how Claude could be used as an agent—working independently to do complex tasks on behalf of a user. While it’s unclear what prior knowledge Claude has about Pokémon from its training data, its system prompt is minimal by design: You are Claude, you’re playing Pokémon, here are the tools you have, and you can press buttons on the screen.

“Over time, I have been going through and deleting all of the Pokémon-specific stuff I can just because I think it’s really interesting to see how much the model can figure out on its own,” Hershey says, adding that he hopes to build a game that Claude has never seen before in order to truly test its limits.

When Claude 3.7 Sonnet played the game, it ran into some challenges: It spent “dozens of hours” stuck in one city and had trouble identifying non-player characters, which drastically stunted its progress in the game. With Claude 4 Opus, Hershey noticed an improvement in Claude’s long-term memory and planning capabilities when he watched it navigate a complex Pokémon quest. After realizing it needed a certain power to move forward, the AI spent two days improving its skills before continuing to play. Hershey believes that kind of multi-step reasoning, with no immediate feedback, shows a new level of coherence, meaning the model has a better ability stay on track.

“This is one of my favorite ways to get to know a model. Like, this is how I understand what its strengths are, what its weaknesses are,” Hershey says. “It’s my way of just coming to grips with this new model that we’re about to put out, and how to work with it.”

Everyone Wants an Agent

Anthropic’s Pokémon research is a novel approach to tackling a preexisting problem—how do we understand what decisions an AI is making when approaching complex tasks, and nudge it in the right direction?

The answer to that question is integral to advancing the industry’s much-hyped AI agents—AI that can tackle complex tasks with relative independence. In Pokémon, it’s important that the model doesn’t lose context or “forget” the task at hand. That also applies to AI agents asked to automate a workflow—even one that takes hundreds of hours.

“As a task goes from being a five minute task to a 30 minute task, you can see the model’s ability to keep coherent, to remember all of the things it needs to accomplish [the task] successfully get worse over time,” Hershey says.

Anthropic, like many other AI labs, is hoping to create powerful agents to sell as a product for consumers. Krieger says that Anthropic’s “top objective” this year is Claude “doing hours of work for you.”

“This model is now delivering on it—we saw one of our early access customers have the model go off for seven hours and do a big refactor,” Krieger says, referring to the process of restructuring a large amount of code, often to make it more efficient and organized.

This is the future that companies like Google and OpenAI are working toward. Earlier this week, Google released Mariner, an AI agent built into Chrome that can do tasks like buy groceries (for $249.99 per month). OpenAI recently released a coding agent, and a few months back it launched Operator, an agent that can browse the web on a user’s behalf.

Compared to its competitors, Anthropic is often seen as the more cautious mover, going fast on research but slower on deployment. And with powerful AI, that’s likely a positive: There’s a lot that could go wrong with an agent that has access to sensitive information like a user’s inbox or bank logins. In a blog post on Thursday, Anthropic says “we’ve significantly reduced behavior where the models use shortcuts or loopholes to complete tasks.” The company also says that both Claude 4 Opus and Claude Sonnet 4 are 65 percent less likely to engage in this behavior, known as reward hacking, than prior models—at least on certain coding tasks.

Anthropic’s chief scientist Jared Kaplan tells WIRED that Claude 4 Opus is the company’s first model to be classified as ASL-3—a safety level that the company uses to evaluate a model’s risks.

“ASL-3 refers to systems that substantially increase the risk of catastrophic misuse compared to non-AI baselines,” the company said in a blog post outlining the policy.

Kaplan says the frontier red team, the safety group in charge of stress testing Anthropic’s models for vulnerabilities, conducted extensive evaluations on Claude 4 Opus and developed new measures to mitigate disastrous risks. In a statement provided by the company, a spokesperson said Sonnet 4 is being released under ASL-2, the baseline safety classification for all of Anthropic’s models. The larger model, Opus 4, is being treated more cautiously under stricter ASL-3 rules unless more testing shows that it can be reclassified as ASL-2.

The goal is to build AI that can handle increasingly complex, long-term tasks safely and reliably, Kaplan says, adding that the field is moving fast, past simple chatbots and toward AI that acts as a “virtual collaborator.” It’s not there yet, and the key challenge for every AI lab is improving reliability long term. “It’s useless if halfway through it makes an error and kind of goes off the rails,” Kaplan says.