Amadou Sow woke to the shrieking of smoke detectors. It was a little after 2:30 am on August 5, 2020, and his house in the suburbs of Denver, Colorado, was ablaze. The 46-year-old rushed to his bedroom door, but a column of smoke and heat forced him back. Panicked, Sow ran to the rear window, broke the screen with his hand, and jumped. The two-story drop fractured his left foot.

Sow’s wife Hawa Ka woke their daughter Adama, who shared their room. She dragged the terrified 10-year-old to the window and pushed her out. Sow tried to catch her but missed. Miraculously, the girl landed on her hands and feet, uninjured. Then it was Ka’s turn. When she leaped, she fell on her back, shattering her spine in two places. Sow barely heard her howls of pain. He was thinking about their 22-year-old son, Oumar.

He couldn’t see any movement inside Oumar’s room. He hurled a rock at the window, but the glass held steady. Despair filled him. Then he noticed Oumar’s car wasn’t in the driveway. He must be working his night shift at 7-Eleven. Thank God! Sow’s family was safe. But what about the others in the house? All told, nine people called 5312 Truckee Street home.

Sow had bought the four-bedroom property in the northeastern suburb of Green Valley Ranch in 2018. The neighborhood was newly built and sparsely populated, cut off from the bulk of the city by miles of prairie grass, giving it an isolated, ghost-town feel. But for Sow, a Senegalese immigrant who usually worked nights at Walmart, the home was a refuge. Not long after his family moved in, his old friend Djibril Diol’s family joined them. Diol—Djiby to his friends—was 29 and a towering 6’8″, a civil engineer who hoped to one day take his skills back to Senegal.

The first fire truck arrived at 2:47 am. By then, the inferno had shattered the windows and plumed the air with smoke. The stench of burning wood filled the neighborhood. When firefighters subdued the blaze enough to get in the front door, they found the small body of a child. Djiby’s daughter Khadija had been two months shy of her second birthday. Farther in sprawled Djiby himself and his 23-year-old wife, Adja.

Next to Adja lay Djiby’s 25-year-old sister, Hassan. She’d only been living in the house for three months. Like Adja, she had dreamed of going back to school to study nursing. She died with her arms still wrapped around her 7-month-old daughter, Hawa Beye. Medical examiners would later conclude that all five died of smoke inhalation, airways coated in black soot, internal organs and muscles burnished “cherry-red” from the heat.

At the same time firefighters were entering the house on Truckee Street, Neil Baker, a homicide detective for the Denver Police Department (DPD), was awoken by a call from his sergeant. Baker—in his fifties with reading glasses, thinning hair, and a rosy complexion—threw on a suit, muttered a hurried goodbye to his wife, and jumped in his car.

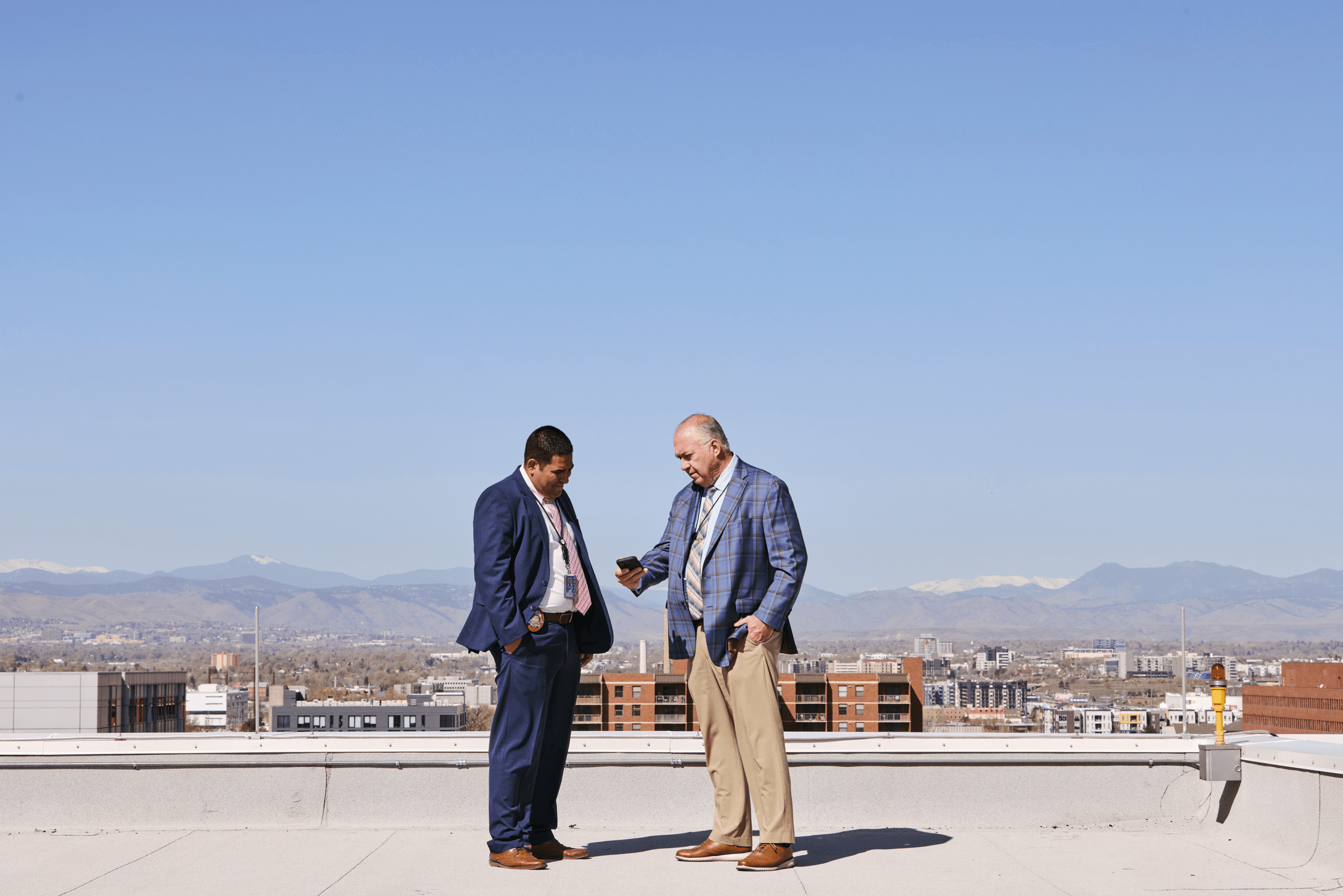

Neil Baker and his police colleagues used Google to help solve the case.Photography: Jimena Peck

After nearly 30 years as a Denver-area cop, Baker knew his way around town. He also knew that Green Valley Ranch was a confusing rabbit’s warren of nearly identical roads. So before he set off, he did something innocuous, something anyone might have done: He Googled the address. And like anyone who Googles something, he was thinking about the search result he wanted—not the packets of data flitting between his device and Google’s servers, not the automated logs of what he was searching for and where he was searching from. But this unseen infrastructure would be key to figuring out what happened at Truckee Street—and it may soon extend the reach of law enforcement into the private lives of millions.

Three weeks before the fire, 16-year-old Kevin Bui went into central Denver to buy a gun. Bui had led a charmed life. His family emigrated from Vietnam before he was born, and though they struggled financially at first—Bui describes his childhood homes as “the projects”—by the time he started high school, his dad’s accounting business had taken off. The family moved to a palatial house in Lakewood, on Denver’s western outskirts, complete with views of the mountains. Bui took to wearing Gucci belts and Air Jordans.

“I disliked school, but I was always really good at it,” Bui tells me. He was athletic too—a swimmer, and an inside linebacker on his school football team, the Green Mountain Rams. He was close with his older sister, Tanya, despite their seven-year age difference. Tanya filled Kevin’s girlfriend’s lashes and bitched to him about her boyfriends. The siblings discussed adopting a dog together.

But there was a darker side to their life: Kevin and Tanya dealt fentanyl and marijuana, often finding customers on Snapchat. Kevin planned to start “carding,” stealing people’s credit card information on the dark web. And he took to amassing weapons.

The guys Bui had arranged to meet in central Denver on that day in July had promised to sell him a gun. Instead, they robbed him of his cash, iPhone, and shoes.

Afterward, Bui bubbled with humiliation. A few weeks earlier, football practice had shut down because of the pandemic. Classes had already been virtual for months. He felt he was “just doing bullshit”: waking up, logging on to Zoom, and returning to bed. The robbery tipped him over the edge. That night, at home in Lakewood, Bui resolved to get even. He pulled up the Find My device feature on his iPad and watched as it pinged his phone. The map zoomed east, past downtown, finally halting at Green Valley Ranch. A pin dropped at 5312 Truckee Street.

The next afternoon, Bui sent a Snapchat message to his friend Gavin Seymour. “I deserved that shit cuz I knew it would happen and still went,” he wrote, according to later court records. “They goin get theirs like I got mine.”

Bui and Seymour ran track together and lived just a four-minute drive apart. But in many ways they were opposites. Where Bui oozed confidence, Seymour was plagued by insecurity. Where Bui excelled academically, Seymour struggled with multiple learning disabilities. In contrast to Bui’s apparently cookie-cutter-perfect family life, Seymour’s parents split when he was young, and his father was largely absent.

In response to Bui’s message, Seymour wrote: “idk why I would let you go alone I’m sorry for that.”

Bui wrote back: “I cant even be mad cuz we used to do the same shit to random niggas.”

But he was mad. More to the point, he was disgraced, his self-image—as a winner, a champ, top dog—shattered. A week later, Bui searched the Truckee Street address 13 times, including on sites like Zillow that detailed its interior layout. And he persuaded Seymour, who was just about to turn 16, and another friend, 14-year-old Dillon Siebert, to help him exact revenge. In late July, Seymour and Siebert also searched the address multiple times.

Bui would later insist they’d planned to simply vandalize the house: hurl rocks at the windows, maybe, or egg the exterior. But sometime in those last hot days of July, things took a darker turn. On August 1, Bui messaged Seymour: “#possiblyruinourfuturesandburnhishousedown.”

Three evenings later, Siebert and Bui went to Party City to buy black theater masks, then grabbed dinner at Wendy’s. They met up with Seymour, and at around 1 am on August 5 the three piled into Bui’s Toyota Camry. They stopped at a gas station, where they filled a red fuel canister to the brim. Then they set off for Green Valley Ranch, cruising past downtown and the Broncos stadium and through an industrial area dotted with smokestacks and semitrailers. The drive took at least 30 minutes, long and boring enough for any one of the teens to express doubt, postpone, chicken out. But it seemed none of them did, not even when they got to 5312 Truckee and saw a minivan—a family vehicle—parked out front.

Green Valley Ranch, in the eastern suburbs of Denver, was a new and sparsely populated neighborhood with a confusing road layout and rows of cookie-cutter family homes. Even longtime city residents found it confusing to navigate.Photography: Jimena Peck

They found the house’s back door unlocked. It’s not clear who doused the gas on the living room walls and floors or who set the flame. When it caught, all three stumbled out to Bui’s car and took off.

When Detective Baker arrived at 5312 Truckee Street two hours later, neighbors swarmed the street, their faces lit by the glow of the flames. The air tasted like ash. He spotted Ernest Sandoval, his partner on the case. Sandoval, nearly 15 years younger than Baker, had moved to homicide from the nonfatal shootings unit only a few weeks earlier.

The officers on the scene told the pair that there could be as many as five fatalities. They suspected faulty wiring had sparked the blaze. It was terrible, tragic—but at least homicide’s job would be straightforward. “We’ll have some reports to write,” Baker remembers thinking. “We’ll have to probably go to the autopsies.” Then a man with melancholy eyes and a faint soul patch approached him. “I have something you should see,” he said. Noe Reza Jr. lived next door. He took out his phone, which held footage from his security cameras.

The video clips started at 2:26 am. They showed three figures in hoodies and masks stealing through the side yard of 5312 Truckee. One points toward the rear of the house. Then they move out of the camera’s sight. Twelve minutes later, the trio sprint back toward the street. At 2:40, flames erupt from the home’s lower floor. Someone screams. The fire consumes the entire house within two minutes.

“Oh, are you kidding me,” Baker thought. Five people had been murdered and their only lead was a few seconds of video that revealed nothing of the criminals’ identity.

That morning, Kevin Bui slept in. Around 10 am, he searched online for news of the fire. There was an abundance. The tragedy had sparked headlines and Twitter threads across the world. The Council on American Islamic Relations issued a statement urging police to consider religious hate as a potential motive. Leaders of Colorado’s African community expressed fear, wondering which of their members might be targeted next. Even Senegal’s president tweeted he’d be watching the case closely.

That’s when the truth began to dawn on Bui. Like many people, he had assumed that Apple’s Find My device software offers exact location tracking. But such programs rely on an unreliable combination of signals from GPS satellites, cell towers, Wi-Fi networks, and other connected devices nearby, and their accuracy can vary from a few feet to hundreds of miles. In the past, this ambiguity has led to threats, holdups, and even SWAT raids at the wrong addresses. (Apple did not respond to a request for comment.)

As he read the news that morning, Bui realized that he had made a terrible mistake. These innocent faces didn’t belong to the guys who had robbed him. He’d killed a family.

That August, Denver’s usually crystalline skies were choked with wildfire smoke. Baker and Sandoval barely noticed. They spent their waking hours in DPD’s 1970s-era HQ, with its fluorescent lighting and gumball machines in the lobby.

The pair had begun their investigation with the usual stuff: interviewing the victims’ friends and family, combing through text messages and financial records. The more they dug, the clearer it became that the families of 5312 Truckee lived quiet, pious lives: work, mosque, home.

The detectives returned to video footage. On clips pieced together from nearby Ring cameras, they saw the car the suspects were in taking a series of wrong turns as it entered the neighborhood, and wildly swerving and mounting curbs on the way out. But the videos weren’t clear enough to identify the exact make or model of the dark four-door sedan. The detectives quickly obtained what are known as tower dump warrants, which required the major phone networks to provide the numbers of all cellular devices in the vicinity of 5312 Truckee during the arson. And they slung a series of so-called geofence warrants at Google, asking the company to identify all devices within a defined area just before the fire. (At the time, Google collected and retained location data if someone had an Android device or any Google applications on their cell phone.)

The warrants returned thousands of phone numbers, which the detectives dumped on Mark Sonnendecker, an agent at the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) who specialized in digital forensics. Sonnendecker, slim and soft-spoken with a face resembling Bill Nye’s, focused on T-Mobile subscribers. He had noticed that a “high percentage” of suspects in previous cases subscribed to the network.

There were 1,471 devices registered to T-Mobile within a mile of the house when it ignited. Using software that visualizes how long it takes a signal to bounce from a cell tower to a phone and back again, Sonnendecker narrowed the list down to the 100 devices nearest to the house. One evening toward the end of August, detectives roamed the area around 5312 Truckee with a cell-phone-tower simulator that captured the IDs of all devices within range. That night, there were 723. Sonnendecker cross-referenced these with the 100 from earlier, eliminating the 67 that showed up on both lists and likely belonged to neighborhood residents who could be ruled out. That left 33 T-Mobile subscribers whose presence in Green Valley Ranch in the early hours of August 5 couldn’t easily be explained.

Investigators considered bringing them in for questioning but decided against it; without any evidence to detain them, they feared spooking the arsonists into fleeing the country. Nothing pointed to any obvious suspects. Still, Sonnendecker remained confident that something would pop up to give police the breakthrough they needed.

But as summer turned to fall, progress on the case began to falter. Hundreds of Crime Stoppers tips were still pouring in, including some from psychics. Baker and Sandoval crisscrossed the state to interrogate a trio found with drugs, guns, and masks in Gypsum and to interview the Senegalese community in the mountain town of Silverthorne. (For decades, West Africans had found work in the ski hub’s many resorts, hotels, and grocery stores.) They even chased a lead to Iowa. “We got pretty hopeful here and there, but it just kind of fizzled out,” recalls Baker.

The detectives were feeling the pressure. In the wake of nationwide Black Lives Matter protests that summer, a petition demanding police stop “undervaluing the lives of BIPOC individuals” and prioritize the investigation into the deaths of the Diol family collected nearly 25,000 signatures. Baker and Sandoval were told not to take on any new cases so they could work this one full time.

At a department meeting in September, Baker and Sandoval pleaded with colleagues for ideas. Was there anything they hadn’t tried—anything at all? That’s when another detective wondered if the perpetrators had Googled the address before heading there. Perhaps Google had a record of that search?

It was like a door they’d never noticed suddenly flung open. They called Sonnendecker and the district attorney, Cathee Hansen. Neither had heard of Google turning over a list of people who had searched for a specific term. In fact, it had been done: in a 2017 fraud investigation in Minnesota, after a series of bombings in Austin in 2018, in a 2019 trafficking case in Wisconsin, and a theft case in North Carolina the following year. Federal investigators also used a reverse keyword search warrant to investigate an associate of R. Kelly who attempted to intimidate a witness in the musician’s racketeering and sexual exploitation trial. But those records had largely been sealed. So, unaware of these precedents, Hansen and Sandoval drafted their warrant from scratch, requesting names, birth dates, and physical addresses for all users who’d searched variations of 5312 Truckee Street in the 15 days before the fire.

Google denied the request. According to court documents, the company uses a staged process when responding to reverse keyword warrants to protect user privacy: First, it provides an anonymized list of matching searches, and if law enforcement concludes that any of those results are relevant, Google will identify the users’ IP addresses if prompted by the warrant to do so. DPD’s warrant had gone too far in asking for protected user information right away, and it took another failed warrant 20 days later and two calls with Google’s outside legal counsel before the detectives came up with language the search giant would accept.

Finally, the day before Thanksgiving 2020, Sonnendecker received a list of 61 devices and associated IP addresses that had searched for the house in the weeks before the fire. Five of those IP addresses were in Colorado, and three of them had searched for the Truckee Street house multiple times, including for details of its interior. “It was like the heavens opened up,” says Baker.

In early December, DPD served another warrant to Google for those five users’ subscriber information, including their names and email addresses. One turned out to be a relative of the Diols; another belonged to a delivery service. But there was one surname they recognized—a name that also appeared on the list of 33 T-Mobile subscribers they’d identified earlier in the investigation as being in the vicinity of the fire. Bui.

The phone was registered to Kevin’s sister Tanya—he may have borrowed it after his was stolen. But a quick scan of the social media accounts of the remaining subscribers on the list yielded three suspects: Kevin Bui, Gavin Seymour, and Dillon Siebert. They were teens, they were friends, and they didn’t live anywhere near Green Valley Ranch. They lived in the Lakewood area, 20 miles away. There was no reason for them to be Googling a residential address so far across town.

“There was a lot of high-fiving,” recalls Sandoval. But it was too soon to fully celebrate. They now had to build a case strong enough to prosecute minors in a high-profile homicide. “We knew this was going to be a big, big, big fight,” Baker says.

On New Year’s Day of 2021, Baker drove by the Bui family’s home and snapped a photo of the 2019 Toyota Camry sitting in the driveway. Another warrant to Google yielded the three teens’ search histories since early July. In the days before the fire, Siebert searched for retailer “Party City.” On Party City’s website, Baker spotted masks similar to those worn by the three perpetrators. The company confirmed that their Lakewood location had sold three such masks hours before the fire. Baker then contacted the shopping complex to get footage from the exterior security cameras that night. He saw that around 6 pm, a 2019 Toyota Camry pulled into the parking lot. “It just snowballed,” says Baker, shaking his head in remembered wonder. “I cannot believe the amount of evidence that we were able to come up with.”

Photography: Jimena Peck

From the teens’ texts and social media, detectives were able to see that the morning after the arson, with the house on Truckee Street still smoldering, Bui and Seymour embarked on a camping trip. A week later, Bui went golfing. A few months after that, Seymour joined the Bui family on vacation in Cancun, where more smiling photos of the two emerged, this time on beaches and boats. The posts enraged the detectives. “Where’s the remorse?” Baker said.

Shortly after 7 am on January 27, police arrested Bui, Seymour, and Siebert. Seymour and Siebert refused to talk, but Bui agreed to an interview and promptly confessed. “He’d had six months of just keeping this inside,” said Baker. “He knew that his time had come.”

For the next 18 months, the case dragged through the court system. It took a year for a judge to rule that Siebert, 14 at the time of the crime, would be charged as a juvenile, while 16-year-olds Bui and Seymour would be tried as adults. If convicted, they faced life in prison.

In June 2022, just when it seemed like the prosecution could finally proceed, Seymour’s lawyers dropped a bombshell. They filed a motion to suppress all evidence arising from the reverse keyword search warrant that DPD had served to Google—the key piece of information that had led detectives to Bui and his friends.

Nearly two years had passed since the Diols were killed in their own home. Many of the victims’ family and friends still moved through their days fearfully and lay awake nights, reliving the nightmare. Now, the detectives had to tell them that the case might be thrown out altogether, potentially allowing the three teens to walk free.

Seymour’s defense argued that, in asking Google to comb through billions of users’ private search history, investigators had cast an unconstitutional “digital dragnet.” It was, they said, the equivalent of police ransacking every home in America. The Fourth Amendment required police to show probable cause for suspecting an individual before getting a warrant to search their information. In this case, police had no reason to suspect Seymour before seeing the warrant’s results. But the judge sided with law enforcement. He likened the search to looking for a needle in a haystack: “The fact that the haystack may be big, the fact that the haystack may have a lot of misinformation in it doesn’t mean that a targeted search in that haystack somehow implicates overbreadth,” he said.

The teens’ fate looked sealed. Then, in January 2023, Seymour’s lawyers announced that the Colorado Supreme Court had agreed to hear their appeal. It would be the first state supreme court in America to address the constitutionality of a keyword warrant. Though the verdict would apply only in Colorado, it would influence law enforcement’s behavior in other states, and potentially the US Department of Justice’s stance on such warrants too.

Baker and Sandoval’s investigation had now been dragged into a legal process that could reshape Americans’ right to search and learn online without fear of retribution. “Even a single query can reveal deeply private facts about a person, things they might not share with friends, family, or clergy,” wrote Seymour’s legal team. “‘Psychiatrists in Denver;’ ‘abortion providers near me;’ ‘is my husband gay;’ ‘does God exist;’ ‘bankruptcy;’ ‘herpes treatment’ … Search history is a window into what people wonder about—and it is some of the most private data that exists.”

The Colorado Supreme Court heard arguments for the case in May 2023. Seymour’s attorney argued that reverse keyword searches were alarmingly similar to geofence warrants, which courts across the country had begun to question. (In August 2024, a federal circuit court of appeals—considered the most influential courts in the United States after the Supreme Court—ruled geofence warrants “unconstitutional under the Fourth Amendment” for never specifying a particular user.)

Denver’s DA, Cathee Hansen—who’d helped detectives craft the warrant in question nearly three years earlier—compared it to querying a bank for suspicious transactions. “You don’t go into each person’s account and scroll through their transaction history to see if it applies to that account,” she said. “You just tap into a database.” Neither search violated any individual’s privacy, she argued.

The judges pushed Hansen on the warrant’s applicability to abortion, outlawed in a growing number of states. “I could see warrants coming in from one of those states to Colorado: Who searched for abortion clinics in Colorado?” said Justice Richard Gabriel. “Under your view, there’d be probable cause for that. That’s a big concern.”

After a five-month wait that Sandoval remembers as “gut-wrenching,” the court finally ruled in October 2023. In a majority verdict, four judges decided the reverse keyword search warrant was legal—potentially opening the door to wider use in Colorado and beyond. The judges argued that the narrow search parameters and the performance of the search by a computer rather than a human minimized any invasion of privacy. But they also agreed the warrant lacked individualized probable cause—the police had no reason to suspect Seymour before they accessed his search history—rendering it “constitutionally defective.”

Because of the ruling’s ambiguity, some agencies remain leery. The ATF’s Denver office says it would only consider using a keyword warrant again if the search terms could be sufficiently narrowed, like in this case: to an address that few would have reason to search and a highly delimited time period. The crime would also have to be serious enough to justify the level of scrutiny that would follow, the ATF says.

Not everyone is so cautious. Baker and Sandoval regularly field calls from police across the country asking for a copy of their warrant. Baker himself is considering using it in another case. And a cottage industry of consultants that, until recently, helped police craft tower-dump warrants now trains them to requisition Google. No systemic data is being collected on how often reverse keyword warrants are being used, but Andrew Crocker, surveillance litigation director of digital rights group the Electronic Frontier Foundation says it’s possible that there have been hundreds of examples to date.

Meanwhile, another case—in which a keyword-search warrant was used to identify a serial rapist—is now before the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. If the warrant is upheld, as it was in Colorado, their use could accelerate nationwide. “Keyword warrants are dangerous tools tailor-made for political repression,” says Crocker. It’s easy to envision Immigrations and Customs Enforcement requesting a list of everyone who searched “immigration lawyer” in a given area, for instance.

By the summer of 2024, all three teens had accepted plea deals: Siebert got 10 years in juvenile detention; Seymour got 40, and Kevin Bui 60, both in adult prison. Bui received the harshest sentence because he’d masterminded the arson. (He was also caught with 92 pills of fentanyl and a couple grams of methamphetamine in his sock while in detention.)

To the victims, none of it was enough. Amadou Beye, the husband of Hassan Diol and father of seven-month-old Hawa, addressed Bui directly at his sentencing. “I will never forget or forgive you for what you did to me,” he said. “You took me away from my wife, the most beautiful thing I had. You took me away from my baby that I will never have a chance to see.” A shudder ran through his tall body. Beye had been in Senegal awaiting a visa when his family was killed. His daughter was born in America, and he never got to meet her.

Bui remained expressionless throughout the victim impact testimonies, save for a furiously bobbing Adam’s apple. Peach fuzz darkened his now 20-year-old jaw. He wore a green jumpsuit, clear-framed glasses, and white shoes. At the end, he read from a crumpled sheet of yellow ruled paper. “I was an ignorant knucklehead blinded by rage. I’m a failure who threw his life away,” he said. “I have no excuses and nobody to blame but myself.”

But when I talked to Bui three months later, he sounded upbeat. “When you go to prison there’s a lifeline,” he told me. Monday through Friday, he took classes on personal growth and emotional intelligence. Aside from that, “I just work out, I chill with some of the guys. We eat together, watch TV, watch sports,” he said. He tried to catch every Denver Broncos and Baltimore Ravens game. Lately, he’d also gotten into Sex and the City.

Not once did Bui complain about the lack of privacy in prison or his exile from the outside world, both physical and digital. Prisoners had little internet access, which, for someone of his generation, who’d grown up online, must have been hard. Did he know who he was without his iPhone, his Snapchat and Instagram? Who were any of us really, without our online personas, our memes and TikToks and the access to the entirety of human knowledge afforded by our devices? As Seymour’s lawyers had argued, didn’t our deepest, truest selves reside online, in our searches and browsers?

All Bui would say was that he was in a good place now. Then he had to go: He was getting a haircut. Online or not, he still had an image to maintain.

Let us know what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor at mail@wired.com.