When clothing designers place an order at Katty Fashion’s factory in Iași, Romania, they expect a bespoke service. If necessary, the factory will even rejig its production lines to make whichever garment a designer commissions. “From order to order, we may have to adapt,” says Eduard Modreanu, the company’s technical lead. “We cannot create one production line or shop floor that fits everyone.”

This adaptability is useful given the many diverse clients and orders Katty Fashion juggles, but it could also help future-proof the company against climate shocks. Katty Fashion is part of an EU-funded project called R3GROUP, which aims to help firms boost the resilience of their supply chains against disruptions caused by climate change and other factors.

“Let’s say there’s going to be flooding in Germany, and we get our materials from Spain,” says Modreanu. “They cannot get here any more.”

As part of the R3GROUP project, Katty Fashion has worked with researchers to build a forensic understanding of where their textiles and accessories such as buttons and zips come from. It has revealed certain potential weak points, such as Spain and Portugal—countries that may increasingly be prone to heat waves or drought in the coming years.

Using this data, along with information gleaned from news and weather reports, the company is developing a digital twin of its supply chain and factory processes that will analyze the vulnerability of its supplier network in real time. If supply issues mean a garment has to be made in a slightly different way, a companion model will also suggest how to reconfigure production lines and worker shifts accordingly.

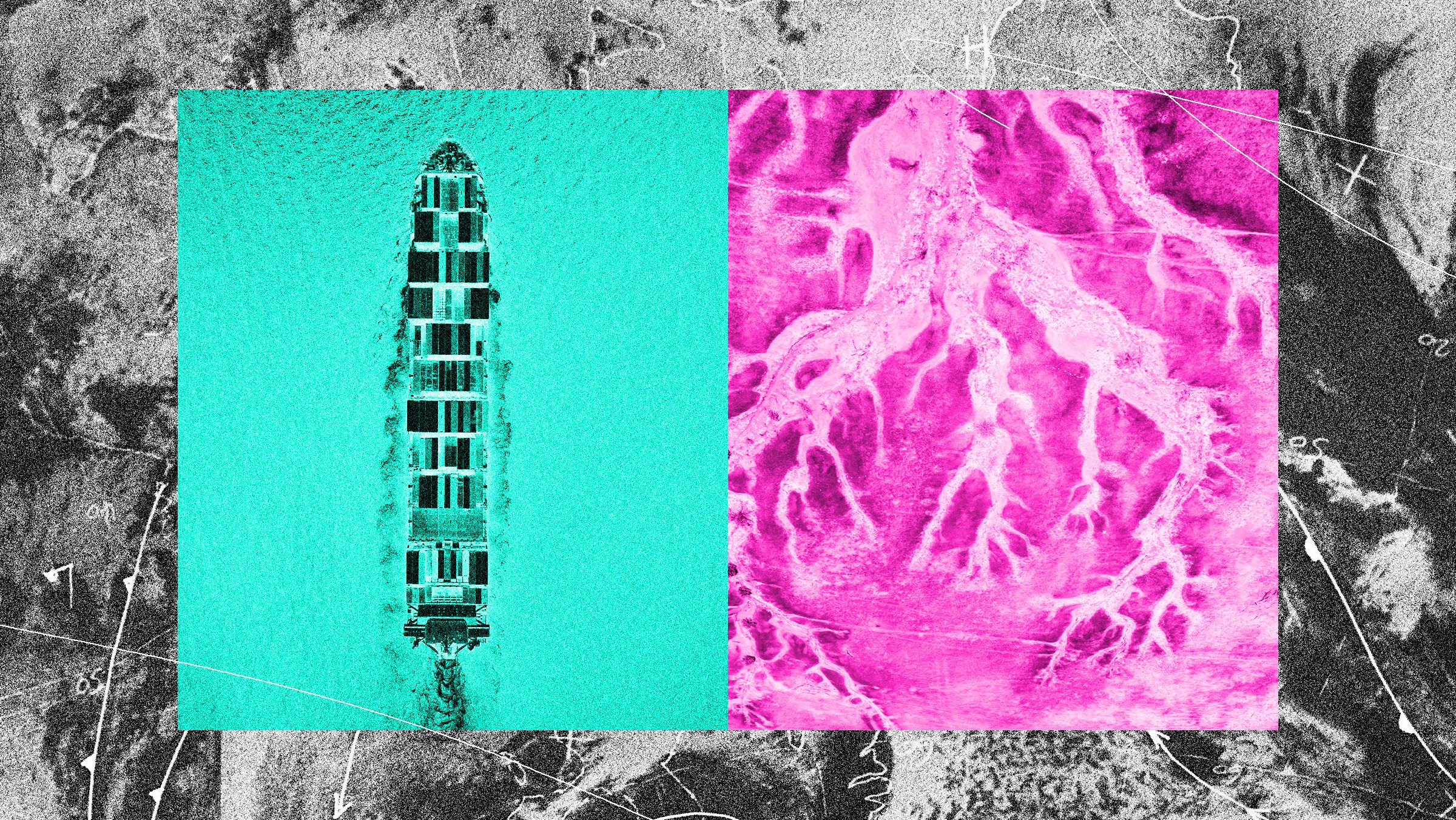

The Covid-19 pandemic highlighted the vulnerability of global supply chains. Companies were so hammered by logistics issues between 2020 and 2022 that many took up a strategy of “reshoring”—opting for suppliers closer to home so as to reduce delays. Some firms even decided to make completely different products, such as the gin and whiskey distilleries that began churning out hand sanitizer.

US president Donald Trump’s recent tariffs provided another shock to the supply chain system. As manufacturers weighed the possibilities of reshoring jobs in the US, many found that bringing the supply chains back to America wouldn’t be cost-effective, and instead contemplated moving factories to territories less impacted by tariffs.

But while the pandemic crunch was solved relatively quickly, and Trump’s tariffs remain unpredictable, the next big shock is likely to last longer. Climate change is already disrupting global supply chains, for instance by exacerbating droughts in Taiwan, where water supplies are crucial for semiconductor manufacturing. Digital twins—virtual models of physical systems—are one way to prepare.

R3GROUP is also working with companies in the metals and plastics industries, says Tjerk Timan, project coordinator and EU project manager at France’s Industrial Technical Centre for Plastics and Composites. But while some firms are actively thinking about how they can adapt to climate-change-related threats, others are more focused on current competition. “We see a bit more of a head-in-the-sand strategy at the moment,” he says.

Abhi Ghadge, associate professor of supply chain management at Cranfield University in the UK, says there has been “a general kind of negligence” in terms of climate resilience, though that is beginning to change.

Building a detailed understanding of a supply chain can, however, be incredibly difficult, especially for smaller companies. Who supplies their suppliers? Which key raw material is about to become subject to a shortage? Tracking such details requires long-term commitment and investment, says Beatriz Royo, associate professor at the MIT-Zaragoza Program in Spain.

Mindful of this, professional services firm Marsh McLennan launched a system called Sentrisk last year that it claims can automatically analyze a company’s shipping manifests and customs clearance records to build up a picture of its supply chain. Sentrisk relies on large language models to read potentially billions of PDF documents, depending on the client in question, and automatically trace where individual materials and parts come from. “It could misread something, of course,” says John Davies, Sentrisk commercial director—though he emphasises that the system relies on artificial intelligence only to read documents, not extrapolate beyond them. There’s no chance of it hallucinating a network of suppliers that doesn’t exist.

Sentrisk combines this supply chain analysis with data on climate risks in specific locations. “If you’re to invest in the construction of a new fabrication plant, maybe you can choose a location that is less likely to be impacted by water shortage,” says Davies.

Another challenge is that digital twins require constant updating, says Dmitry Ivanov, professor of supply chain and operations management at the Berlin School of Economics and Law. “It’s not like a house that you build and the house exists in this form for 100 years,” he says. “Supply chains change every day.”

And while we have a reasonably good idea of how climate change will affect the planet as a whole in the coming years, the exact location, timing, and magnitude of specific disasters is tricky to predict. This is where new tools for climate-risk modeling and extreme weather prediction come in. Semiconductor and AI giant Nvidia has a platform called Earth-2, which it hopes will address this challenge, with the help of other organizations including the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The idea is to use AI to provide earlier warnings of a drought or flood, or to more accurately predict how a storm will develop. Some parts of the world only have relatively high-level information about current weather patterns; Earth-2 uses the same type of AI that sharpens pictures in your smartphone camera app to simulate higher-resolution data. “This is really useful, especially for small regions,” says Dion Harris, senior director of high-performance computing and AI factory solutions at Nvidia.

Companies can feed their own data into Earth-2 to improve predictions even further. They might use the platform to model climate and weather impacts in specific geographies, but the overall scope of the project is vast. “We are building the foundational elements to create a digital twin of the Earth,” Harris says.