Automakers and tech developers testing and deploying self-driving and advanced driver-assistance features will no longer have to report as much detailed, public crash information to the federal government, according to a new framework released today by the US Department of Transportation.

The moves are a boon for makers of self-driving cars and the wider vehicle technology industry, which has complained that federal crash-reporting requirements are overly burdensome and redundant. But the new rules will limit the information available to those who watchdog and study autonomous vehicles and driver-assistance features—tech developments that are deeply entwined with public safety but which companies often shield from public view because they involve proprietary systems that companies spend billions to develop.

The government’s new orders limit “one of the only sources of publicly available data that we have on incidents involving Level 2 systems,” says Sam Abuelsamid, who writes about the self-driving-vehicle industry and is the vice president of marketing at Telemetry, a Michigan research firm, referring to driver-assistance features such as Tesla’s Full Self-Driving (Supervised), General Motors’ Super Cruise, and Ford’s Blue Cruise. These incidents, he notes, are only becoming “more common.”

The new rules allow companies to shield from public view some crash details, including the automation version involved in incidents and the “narratives” around the crashes, on the grounds that such information contains “confidential business information.” Self-driving-vehicle developers, such as Waymo and Zoox, will no longer need to report crashes that include property damage less than $1,000, if the incident doesn’t involve the self-driving car crashing on its own or striking another vehicle or object. (This may nix, for example, federal public reporting on some minor fender-benders in which a Waymo is struck by another car. But companies will still have to report incidents in California, which has more stringent regulations around self-driving.)

And in a change, the makers of advanced driver-assistance features, such as Full Self-Driving, must report crashes only if they result in fatalities, hospitalizations, air bag deployments, or a strike on a “vulnerable road user,” like a pedestrian or cyclist—but no longer have to report the crash if the vehicle involved just needs to be towed.

“This does seem to close the door on a huge number of additional reports,” says William Wallace, who directs safety advocacy for Consumer Reports. “It’s a big carve-out.” The changes move in the opposite direction of what his organization has championed: federal rules that fight against a trend of “significant incident underreporting” among the makers of advanced vehicle tech.

The new DOT framework will also allow automakers to test self-driving technology with more vehicles that don’t meet all federal safety standards under a new exemption process. That process, which is currently used for foreign vehicles imported into the US but is now being expanded to domestically made ones, will include an “iterative review” that “considers the overall safety of the vehicle.” The process can be used to, for example, more quickly approve vehicles that don’t come with steering wheels, brake pedals, rearview mirrors, or other typical safety features that make less sense when cars are driven by computers.

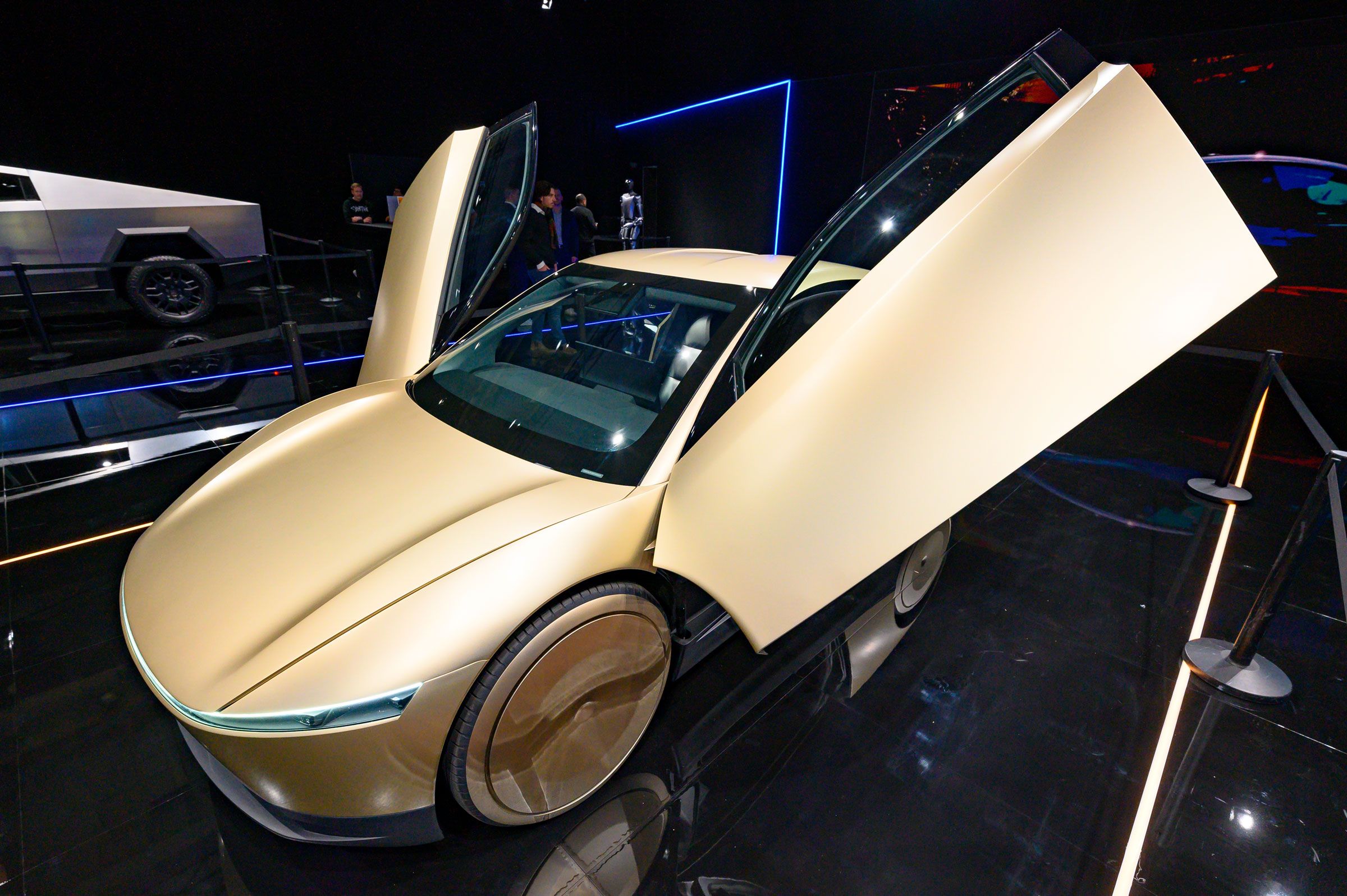

One company in particular emerges as a winner: Elon Musk’s Tesla, which now will be able to curtail public reporting on its Autopilot and Full Self-Driving (Supervised) features, and may enjoy an easier road to federal safety approval for its upcoming Cybercab, a two-seat, purpose-built robotaxi that does not have a steering wheel or brakes.

“The company that probably benefits the most from that is Tesla,” Abuelsamid says. Though the Transportation Department cited safety as the number one motivator behind the new rules, “there’s nothing in these changes that actually prioritizes safety,” he says.

A spokesperson for the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration did not respond to questions about Tesla. Tesla, which disbanded its press team five years ago, did not respond to a request for comment.

In a video message posted to X, DOT secretary Sean Duffy said the new automated vehicle framework aimed to increase commercial deployment of new car technology. “America is in the middle of an innovation race with China, and the stakes couldn’t be higher,” he said.

In a memo, an NHTSA official said the changes were only the first step in an effort to “improve the efficiency and effectiveness” of the process through which new vehicle tech is allowed on roads.

Vehicle industry groups applauded the changes. The Autonomous Vehicle Industry Association, an organization that represents several autonomous vehicle technology companies (though, notably, not Tesla) called the DOT’s announcement a “bold and necessary step in developing a federal policy framework for autonomous vehicles.” John Bozzella, the president and CEO of the Alliance for Automotive Innovation, an automotive trade organization, said the announcement is “a signal that AV policy in America isn’t an afterthought anymore.”

The changes to the program are not as drastic as some safety advocates had feared. Prior to President Donald Trump’s inauguration, Reuters reported that the transition team considered scrapping all government crash-reporting requirements related to self-driving and advanced vehicle technology. Though this week’s changes curtail some of the data released and eliminate some redundancies that made the data more difficult to understand and handle, companies deploying self-driving cars are still required to report crash information to the feds.

Noah Goodall, an independent researcher who studies autonomous vehicles, says the changes may make it harder for outsiders to spot or understand patterns in self-driving vehicles’ mistakes—though also notes the public database on crashes has been difficult to work with since it was launched in 2021. “You’re getting less reporting now,” he says. “From my perspective, more data is good.”