In 1974, the United State Congress passed the Privacy Act in response to public concerns over the US government’s runaway efforts to harness Americans’ personal data. Now Democrats in the US Senate are calling to amend the half-century-old law, citing ongoing attempts by billionaire Elon Musk’s so-called Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) to effectively commit the same offense—collusively collect untold quantities of personal data, drawing upon dozens if not hundreds of government systems.

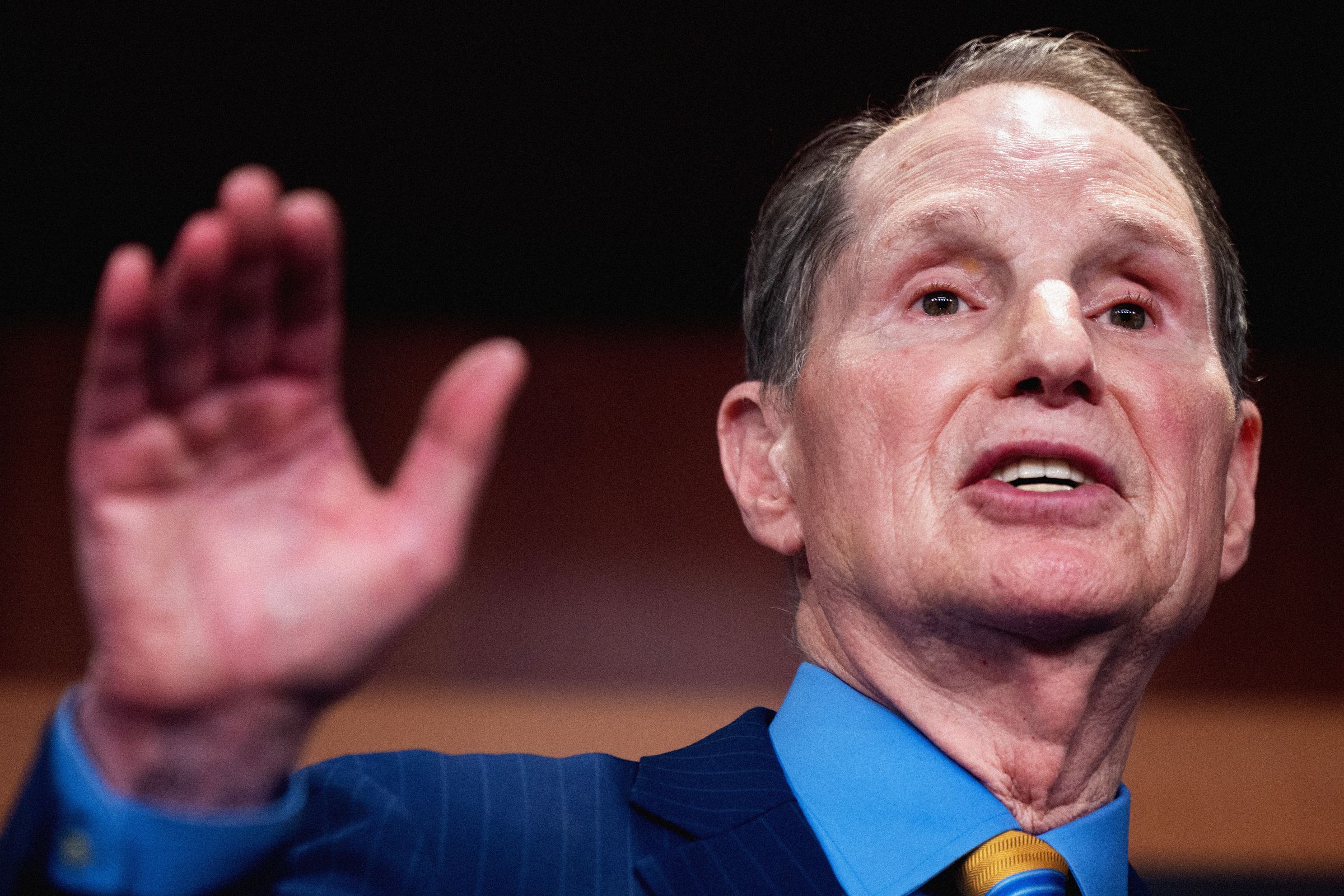

On Monday, Democratic senators Ron Wyden, Ed Markey, Jeff Merkley, and Chris Van Hollen introduced the Privacy Act Modernization Act of 2025—a direct response, the lawmakers say, to the seizure by DOGE of computer systems containing vast tranches of sensitive personal information—moves that have notably coincided with the firings of hundreds of government officials charged with overseeing that data’s protection. “The seizure of millions of Americans’ sensitive information by [President] Trump, Musk and other MAGA goons is plainly illegal,” Wyden tells WIRED, “but current remedies are too slow and need more teeth.”

The passage of the Privacy Act came in the wake of the McCarthy era—one of the darkest periods in American history, marked by unceasing ideological warfare and a government run amok, obsessed with constructing vast record systems to house files on hundreds of thousands of individuals and organizations. Secret dossiers on private citizens were the primary tool for suppressing free speech, assembly, and opinion, fueling decades’ worth of sedition prosecutions, loyalty oaths, and deportation proceedings. Countless writers, artists, teachers, and attorneys saw their livelihoods destroyed, while civil servants were routinely rounded up and purged as part of the roving inquisitions.

The first privacy law aimed at truly reining in the power of the administrative state, the Privacy Act was passed during the dawn of the microprocessor revolution, amid an emergence of high-speed telecommunications networks and “automated personal data systems.” The explosion in advancements coincided with Cassandra-like fears among ordinary Americans about a rise in unchecked government surveillance through the use of “universal identifiers.”

A wave of such controversies, including Watergate and COINTELPRO, had all but annihilated public trust in the government’s handling of personal data. “The Privacy Act was part of our country’s response to the FBI abusing its access to revealing sensitive records on the American people,” says Wyden. “Our bill defends against new threats to Americans’ privacy and the integrity of federal systems, and ensures individuals can go after the government when officials break the law, including quickly stopping their illegal actions with a court order.”

The bill, first obtained by WIRED last week, would implement several textual changes aimed at strengthening the law—redefining, for instance, common terms such as “record” and “process” to more aptly comport with their usage in the 21st century. It further takes aim at certain exemptions and provisions under the Privacy Act that have faced decades’ worth of criticism by leading privacy and civil liberties experts.

While the Privacy Act generally forbids the disclosure of Americans’ private records except to the “individual to whom the records pertain,” there are currently at least 10 exceptions that apply to this rule. Private records may be disclosed, for example, without consent in the interest of national defense, to determine an individual’s suitability for federal employment, or to “prevent, control, or reduce crime.” But one exception has remained controversial from the very start. Known as “routine use,” it enables government agencies to disclose private records so long as the reason for doing so is “compatible” with the purpose behind their collection.

The arbitrary ways in which the government applies the “routine use” exemption have been drawing criticism since at least 1977, when a blue-ribbon commission established by Congress reported that federal law enforcement agencies were creating “broad-worded routine uses,” while other agencies were engaged in “quid pro quo” arrangements—crafting their own novel “routine uses,” as long as other agencies joined in doing the same.

Nearly a decade later, Congress’s own group of assessors would find that “routine use” had become a “catch-all exemption” to the law.

In an effort to stem the overuse of this exemption, the bill introduced by the Democratic senators includes a new stipulation that, combined with enhanced minimization requirements, would require any “routine use” of private data to be both “appropriate” and “reasonably necessary,” providing a hook for potential plaintiffs in lawsuits against government offenders down the road. Meanwhile, agencies would be required to make publicly known “any purpose” for which a Privacy Act record might actually be employed.

Cody Venzke, a senior policy counsel at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), notes that the bill would also hand Americans the right to sue states and municipalities, while expanding the right of action to include violations that could reasonably lead to harms. “Watching the courts and how they’ve handled the whole variety of suits filed under the Privacy Act, it’s been frustrating to see them not necessary take the data harms seriously or recognize the potential eventual harms that could come to be,” he says. Another major change, he adds, is that the bill expands who’s actually covered under the Privacy Act from merely citizens and legal residents to virtually anyone physically inside the United States—aligning the law more firmly with current federal statutes limiting the reach of the government’s most powerful surveillance tools.

In another key provision, the bill further seeks to rein in the government’s use of so-called “computer matching,” a process whereby a person’s private records are cross-referenced across two agencies, helping the government draw new inferences it couldn’t by examining each record alone. This was a loophole that Congress previously acknowledged in 1988, the first time it amended the Privacy Act, requiring agencies to enter into written agreements before engaging in matching, and to calculate how matching might impact an individual’s rights.

The changes imposed under the Democrats’ new bill would merely extend these protections to different record systems held by a single agency. To wit, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) has one system that contains records on “erroneous tax refunds,” while another holds data on the “seizure and sale of real property.” These changes would ensure the restrictions on matching still apply, even though both systems are controlled by the IRS. What’s more, while the restrictions on matching do not currently extend to “statistical projects,” they would under the new text, if the project’s purpose might impact the individuals’ “rights, benefits, or privileges.” Or—in the case of federal employees—result in any “financial, personnel, or disciplinary action.”

The Privacy Act currently imposes rather meager criminal fines (no more than $5,000) against government employees who knowingly disclose Americans’ private records to anyone ineligible to receive them. The Democrats’ bill introduces a fine of up to $250,000, as well as the possibility of imprisonment, for anyone who leaks records “for commercial advantage, personal gain, or malicious harm.”

The bill has been endorsed by the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) and Public Citizen, two civil liberties nonprofits that are both engaged in active litigation against DOGE.

“Over 50 years ago, Congress passed the Privacy Act to protect the public against the exploitation and misuse of their personal information held by the government,” Markey says in a statement. “Today, with Elon Musk and the DOGE team recklessly seeking to access Americans’ sensitive data, it’s time to bring this law into the digital age.”