Artificial intelligence has to date been enlisted as a bogeyman in cultural circles: Software will take the jobs of writers and translators, and AI-generated images ring the death toll for illustrators and graphic designers.

Yet there’s a corner of high culture where AI is taking on a starring role as hero, not displacing the traditional protagonists—art experts and conservators—but adding a powerful, compelling weapon to their arsenal when it comes to fighting forgeries and misattributions. AI is already exceptionally good at recognizing and authenticating an artist’s work, based on the analysis of a digital image of a painting alone.

AI’s objective analysis has thrown a wrench into this traditional hierarchy. If an algorithm can determine the authorship of an artwork with statistical probability, where does that leave the old-guard art historians whose reputations have been built on their subjective expertise? In truth, AI will never replace connoisseurs, just as the use of x-rays and carbon dating decades ago did not. It is simply the latest in a line of high-tech tools to assist with authentication.

A good AI must be “fed” a curated dataset by human art historians to build up its knowledge of an artist’s style, and human art historians must interpret the results. Such was the case in November 2024, when a leading AI firm, Art Recognition, published its analysis of Rembrandt’s The Polish Rider—a painting that famously confounded scholars and led to many arguments as to how much, if any of it, had actually been painted by Rembrandt himself. The AI precisely matched what most connoisseurs had posited about which parts of the painting were by the master, which were by students of his, and which involved the hand of over-enthusiastic restorers. It is particularly compelling when the scientific approach confirms the expert opinion.

We humans find hard scientific data more compelling than personal opinion, even when that opinion comes from someone who seems to be an expert. The so-called “CSI effect” describes how jurors perceive DNA evidence as more persuasive than even eyewitness testimony. But when expert opinion (the eyewitnesses), provenance, and scientific tests (the CSI) all agree on the same conclusion? That’s as close to a definitive answer as one can get.

But what happens when the owner of a work that, at first glance, looks totally inauthentic to the point of being laughable, recruits a slick firm with the task of gathering forensic evidence to support a preferable attribution?

Lost and Found

Back in 2016, an oil painting surfaced at a flea market in Minnesota and was bought for less than $50. Now its owners are suggesting that it could be a lost Van Gogh, and therefore would be worth millions. (One estimate suggests $15 million.) The answer—at least to anyone with functioning eyeballs and a passing familiarity with art history—was a resounding “nah.” The painting is stiff, clumsy, utterly lacking the feverish impasto and rhythmic brushwork that define the Dutch artist’s oeuvre. Worse still, it bore a signature: Elimar. And yet, this dubious painting has become the center of a high-stakes battle for authenticity, one in which scientific analysis, market forces, and wishful thinking collide.

The owners of the “Elimar Van Gogh,” as it has come to be derisively known in art circles, are now an art consultancy group called LMI International. They are investing heavily in getting experts to say what they want to hear: that it is, in fact, a genuine Van Gogh. This is where things get murky. The world of art authentication is not a straightforward affair. Unlike the hard sciences, art history deals in probabilities, connoisseurship, and competing expert opinions. It is also, crucially, an industry driven by financial incentives. If the painting is deemed real, its value skyrockets. If it’s deemed a fake, or rather in this case a derivative work by someone named Elimar who daubed a bit on canvas, distantly inspired by Van Gogh perhaps, but with none of his talents, it’s virtually worthless—about as valuable as you might expect to find at a flea market in Minnesota for under 50 bucks. This imbalance in stakes has led to a dangerous trend: hiring experts not to determine authenticity, but to affirm it.

There are precedents. The so-called “Lost Jackson Pollock” was a painting found at a California flea market in the early 1990s by Teri Horton, a retired truck driver with no art background. She purchased the large, chaotic canvas for $5, unaware that its swirling drips and splatters bore a resemblance to the work of Jackson Pollock. When someone pointed out the similarity, Horton embarked on a decades-long quest to authenticate it that was documented in the 2006 film Who the #$&% Is Jackson Pollock?

Horton’s attempts at authentication clashed with the traditional, often opaque, art world. Major Pollock experts refused to endorse the painting, citing the lack of provenance, as there was no documented link to Pollock’s studio. In response, Horton turned to forensic science. She hired Peter Paul Biro, a controversial fingerprint expert, who claimed to have found a fingerprint on the painting that matched one on a paint can in Pollock’s studio. This was not enough to sway the art establishment. On the contrary, a 2010 New Yorker feature by David Grann called “Mark of a Masterpiece” thoroughly discredited Biro and his authentication work. Biro then sued for libel and lost. Despite extensive efforts, no museum or auction house accepted the work as genuine, leaving it unsold and its status forever in limbo—a stark example of how difficult (and subjective) authentication can be when money, reputations, and scientific claims collide. That’s what happens when such an approach goes wrong. Will the Elimar owners have better luck now that new technology is available to provide newer ways of authenticating art?

Real Talk

Art has traditionally been authenticated in one of three ways: connoisseurship, provenance research, and forensic testing. Connoisseurship is the oldest and remains the default method; it relies on the opinion of self-proclaimed experts who physically examine the object in question and tell you what they think. Provenance research follows the documented history of an object, and is useful for establishing whether such an object is documented as having ever existed—mentioned in archival materials, letters, catalogues raisonnés, or gallery listings—or whether a chain of ownership and attribution is accounted for that suggests that the work was not stolen and that it has been considered authentic for an extended period of time. Forensic testing involves conservators examining the object with methods like carbon dating, x-rays, and infrared spectroscopy to see if there are anachronistic elements or if all appears as it should be for an artwork of the era and authorship that the experts suppose it to have. The owners of the Elimar painting are hoping that one or more of these three approaches will suggest that their flea market painting is indeed a Van Gogh.

Enter LMI Group International, a data science firm that bought the “Elimar” from the original owner and assembled a 458-page document that claims to authenticate the painting. The phrasing is important—because their role is not to assess whether it is by Van Gogh, but rather to find a way to confirm that it is. This distinction is everything. If the painting is declared genuine, the owners, the experts, and the auction houses involved all stand to profit handsomely. If it is declared inauthentic, the only winners are the people who weren’t taken in by the charade in the first place. Given these dynamics, skepticism should be the default response.

As of writing, not one renowned Van Gogh expert has publicly endorsed the painting. The Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, widely regarded as the foremost authority on the artist’s oeuvre, has twice evaluated the painting and concluded that it is not an authentic Van Gogh. It did this first in 2019 when, based on stylistic features, it determined the work could not be attributed to Van Gogh. Even after reviewing new information presented by LMI Group in an extensive report, the museum doubled down, reaffirming its stance in January 2025, stating: “We maintain our view that this is not an authentic painting by Vincent van Gogh.”

Other experts agreed. Famed American art critic Jerry Saltz posted on social media, “Next up: A newly discovered Michelangelo, signed ‘Steve.’”

So if it’s not a Van Gogh, what is it? Some art historians have proposed that “Elimar” may be the work of Henning Elimar, a lesser-known Danish artist. This theory is supported by similarities in signature and style between the painting in question and known works by Henning Elimar.

Hang on. An Elimar painting signed “Elimar” could actually be by Elimar? That certainly sounds more plausible.

So connoisseurs are not helping out the owners of the former flea-market painting. What does the provenance have to say about it? Typically, a documented chain of ownership is crucial in establishing a work’s authenticity. In the case of “Elimar,” no such documentation exists before its 2016 appearance, making it challenging to attribute the painting to Van Gogh.

Additionally, comprehensive catalogues raisonnés, such as those compiled by Jacob Baart de la Faille and Jan Hulsker, do not list anything resembling “Elimar” among Van Gogh’s known works. These catalogues aim to document all recognized artworks by the artist, and the absence of something that could fit the description of “Elimar” further discredits claims of its authenticity.

How about forensics?

Authentication Factor

Since the era of the “Lost Jackson Pollock” a new authentication method has arrived, one that harnesses AI and machine learning.

The aforementioned Art Recognition has already run its own AI analysis on the painting—and the results are damning. Company founder Carina Popovici tells me that according to Art Recognition’s closed AI algorithm, there is a 97 percent certainty that the painting is not by Van Gogh. This is a significant result and one that, until now, has not been made public.

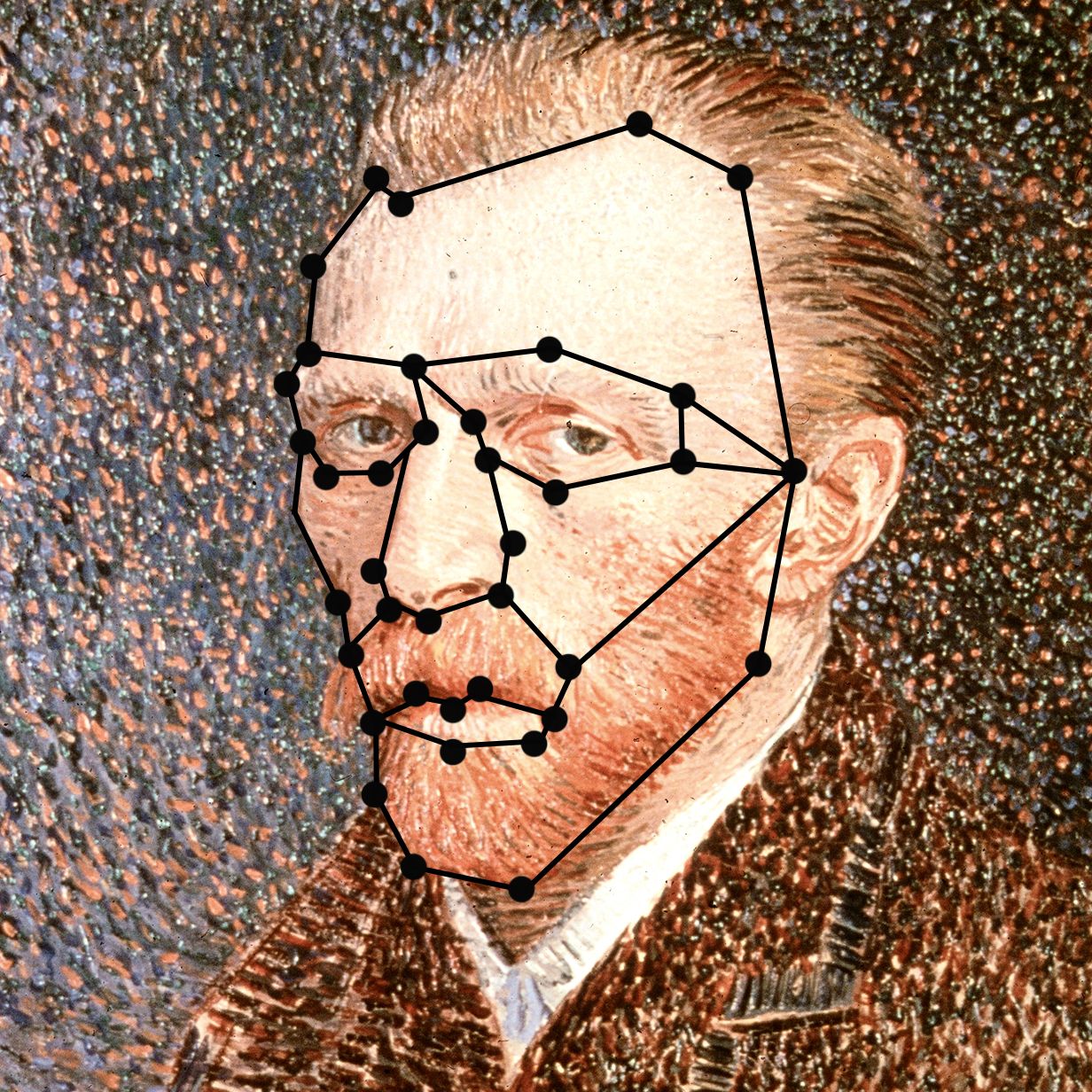

Art Recognition, based in Zurich, has trained its algorithm on 834 verified authentic Van Gogh artworks and 1,785 inauthentic images (to teach it what not to be fooled by). The program can analyze brushstroke patterns, color composition, and other features imperceptible to the human eye. (Full disclosure: I have advised Art Recognition in my capacity as an author and researcher on forgery and art theft, but my opinion on the “Elimar” was formed long before my involvement with the company.)

The fact that Art Recognition’s AI has come back with such a strong negative result should, in theory, settle the matter. And yet, the painting is still being championed by LMI Group International, whose mission appears to be less about discovery and more about justification. LMI’s website still bears the headline: “Elimar Returns: A Newly Identified Work by Vincent van Gogh. Read the entire report establishing the authorship of this painting by Vincent van Gogh.” Despite this, no one of importance seems to be convinced. LMI supposedly paid around $1 million to have the painting authenticated. That is an astounding sum—authenticating a painting should cost far less than that. (Art Recognition charges only four figures to test via its AI system.)

This is not an isolated case. The art market has long had a problem with potential conflicts of interest in authentication. The stakes are too high, and there is often more financial incentive in declaring a work real than in dismissing it as a fake or misattributed work of little value.

The art world prides itself on connoisseurship—the ability of trained experts to recognize an artist’s hand through years of study. The saga of the “Elimar Van Gogh” serves as a case study in how art authentication can go astray when it is led by hypothesis bias. In brief: We want this to be by Van Gogh, make a case to confirm it. Authentication is a process that, at its best, should be about discovery and scholarly rigor. But too often it is driven by the pursuit of profit, leading to situations where scientific findings are ignored in favor of more convenient conclusions, or where data is manufactured or interpreted in a way to prove a hypothesis rather than allow for the most logical, objective conclusion.

In cases like this one, AI can provide a crucial check on the excesses of the market. It is objective, dispassionate, and—unlike human experts—not subject to financial motivation. And in this instance, it has done what should have been obvious from the start: It has called out the painting as not by the famous artist in question.

With AI authentication gaining traction, and with the art world increasingly aware of the conflicts of interest inherent in traditional methods, there is hope for a more transparent future. Importantly, AI is a forensic tool that can test a work in question using a digital image alone, thereby obviating the need to send a fragile painting on an expensive and risky trip to a lab. This makes it a powerful assistant to, but not a replacement for, human experts, researchers, and conservators around the world.

For now, one thing is certain: If a painting doesn’t look like a Van Gogh, isn’t signed by Van Gogh, and is confirmed by AI not to be a Van Gogh, then—despite what the market might wish—it simply isn’t a Van Gogh.