Love is simple, says Reverend Paul Anthony Daniels, because “in its most visceral form,” it boils down to three things: spit, semen, and sweat. Ok, maybe four. Sometimes there is blood. “To share love in that way is so visceral.”

I have a confession, I tell Daniels. I have never been in love—not in the Hallmark movie kind of way, at least—but find myself craving it the older I get, so I’m a little stunned to hear him describe it with such candor. You know, being a priest and all. God is in people, he says. Which means, God is also in sex.

Daniels loves love. He seeks it in everything he does, he tells me, but especially in people. It’s part of his job as an Episcopal priest and a “mediator of Christ’s love in the world.” Ceremonially, he is “a steward of the sacraments—the Eucharist, baptism, marriage, confirmation. I invite people into a relationship with God through those sacred ritual acts. But it’s also more than that.”

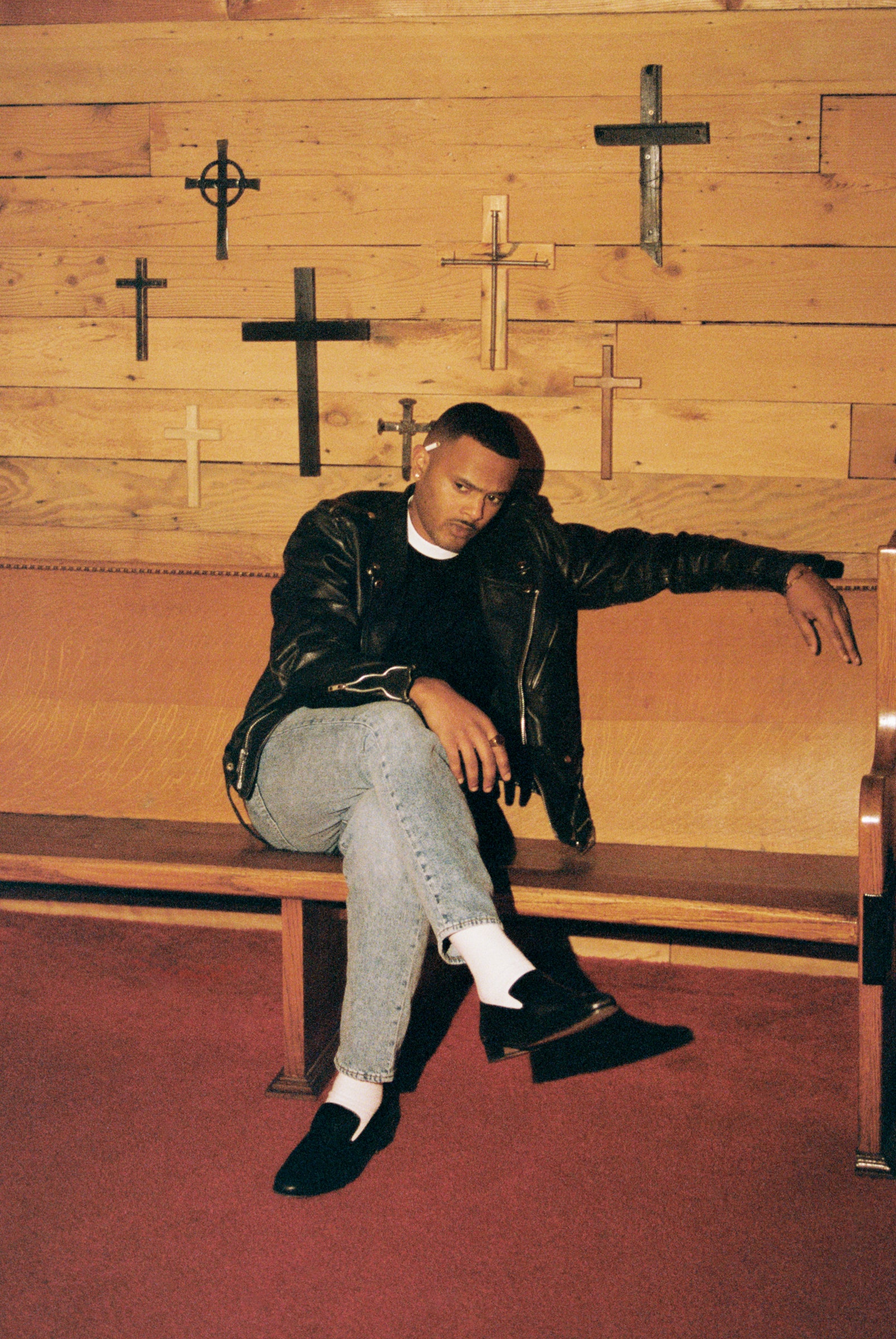

Rev. Paul Anthony DanielsPhotograph: Carianne Older

It’s the more part that’s got me in Los Angeles’ Koreatown sitting across from him in his apartment as he sips from a whiskey glass, going on about desire, salvation, and all the irresistible ways people come together. A graduate of Morehouse College and Yale Divinity School, Daniels, 34, is not your average Episcopal priest. He’s something of a trailblazer. A rogue in a clerical collar.

Although faith has been central to Daniels’ identity since his boyhood in Raleigh, North Carolina, he also grew up with an abiding appreciation for music—Stevie Wonder, Chaka Khan, John Mayer. In 2007, he auditioned for season 7 of American Idol and made it all the way to Hollywood Week. “As soon as I walked to the hotel in Pasadena I knew that I was not slated to be one of the young people that they were going to pay attention to,” he says. “All the producers had their eyes on David Archuleta.”

He returned to Raleigh and dug deeper into what eventually became his calling. Being openly gay and Christian meant he had the capacity to “say and do things that could open doors of possibility for people.” Daniels has since made that into his life’s work. Hence the whole spit, semen, sweat thing. There’s a bigger context to all of this, he wants me to know. It also helps that he often gives lectures on these very topics—“sexual socialities as theological questions”—in addition to being a PhD candidate at Fordham University.

Most people today have what Daniels calls a “consumerist devotion built around the consumption of material things—bodies, clothes, objects.” The worst instances of that are on social media. He encounters it on Instagram (his favorite dating platform) and the various hookup apps he frequents. Social media, he says, has become a “site of worship—pun intended.”

Jason Parham: As a priest who uses dating and hookup apps, how do you navigate your relationship to desire?

Paul Anthony Daniels: One of my life mottos is “Follow desire.”

Where did that come from?

Michel de Certeau, a French Jesuit and literary theorist, said the mystic is always on the move because God cannot be circumscribed to any one place or any one thing. My relationship to the holy has been in the spirit of that kind of mystical movement. There’s a queerness in the unsettledness. I’ve grown closer to God by growing closer to a deeper sense of who I am and who God made me to be, so there’s that. But also I love sex. There’s nothing like meeting another body to which you can surrender. Where all of yourself, all of your guards, all of your insecurities, all of your fear evaporates in the image of love.

Almost like God.

Yes, almost like God. A person becomes the image—and idol—of love. To share love in that way is so visceral. Literally, it is spit. It is semen. It is sweat. Sometimes it is blood.

All of that.

And to have all of that in the context of tenderness, of course shame would be evacuated. That’s precisely the image of Jesus on the cross. It is visceral and it is gross and it is suffering, but that is also the image of our salvation. That sacrifice happens for our capacity to see ourselves as no longer subject to the state, no longer subject to powers that would attempt to shame and silence us. Jesus gives his life that we might see ourselves more clearly and more bravely. That’s also what happens in the context of a sexual relationship. That’s why I’m always going to follow desire, because in it is liberation. One of the greatest sins is that people have had their capacity to be brave in their desires stolen. The sin is not sex.

What apps have helped facilitate your pursuit of desire?

Instagram, Hinge, Tinder. I’m also a newly minted Jack’d user. My only relationship in LA began on Hinge. Instagram is basically a dating app for me. My profile is curated mostly for the sake of flirting.

Photograph: Carianne Older

Really?

There is nothing on my grid that is in line with my calling, in terms of being inspirational and accompanying people into a new understanding of God. I save most of that for my Story. That said, I am constantly aware of the ways in which my presence on social media, and my interactions with people on social media, may fall short of the deeper meaning that my calling impresses upon me. But I also have a responsibility to talk about and share with others how I’m seeing and living in the world.

So you feel obligated to post?

I do. I feel obligated to post about how I interpret the world. I hate that, but I also love it. I hate it because I don’t want to participate in a consumerist exercise where it’s all about affect and, you know, pithy sayings and being sentimental.

Yes.

At the same time, my calling is to people who have been exiled and ostracized by the church. So if I’m not in some way fully embodied as a witness in spaces where people live and exist and talk—if I’m not present in the spaces where people are—then I’m not living up to the call that I have, which is to give people permission to be freer and to be liberated.

What’s an example of that?

There was one Tinder date during my time in New York City that completely changed my life. It changed my perception of who I was in relation to other people as a gay Black man who is also a priest.

In what way?

I was working at a cathedral and lived on the campus of the cathedral. This person was a former service member—a gay Black guy from the South. When he came over to my apartment, he sat down and said, “I feel redeemed.” I was like, Ugh.

Why that reaction?

Personally I have no desire to be the savior for my partner. That’s not interesting to me at all. But he followed up very quickly. He said, “I feel redeemed not by you but by being in this space. Being intimate in this space is my way of saying I can be who I am in the face of this thing that was detrimental to my development.”

He felt stunted by the institution of the church.

It made me realize there may be a lot more going on in how I share intimacy with other people, and I need to be able to make space for that.

Was the sex good?

[Pauses.] That’s why it didn’t work. I would never say it was bad sex, the chemistry just wasn’t intuitive.

Is that a typical experience?

No, but dating apps have brought to the surface a very difficult relationship I have to my body.

How so?

I’ve developed a deeply self-conscious relationship to my body. Sometimes when things don’t move forward with certain guys, I know it’s because I don’t meet a particular standard of excellence in terms of what my body looks like. I had a guy say to me, “I’m gonna need you to have more muscle mass.” This was someone that I adored, and still adore.

That’s tough.

I can’t help to think that a major part of the reason it fell apart was because of a particular kind of physical inadequacy. So dating apps have forced me to come to grips with what I think about my body, why I think about my body in that way, and how I think about other people’s bodies.

There does seem to be a very unhealthy culture around body standards on gay hookup apps especially.

I was on Jack’d the other day looking. I opened my messages, and every avatar had their shirt off. Every single one. I remember thinking, I didn’t choose all of those people; they came to my profile. Which is also crazy, because I don’t have an image up, it’s blank.

Photograph: Carianne Older

Why blank?

I enjoy the mystery. But my profile is also that way, because on Jack’d I don’t feel like I have anything to offer by way of visuality. It is all about a broad shoulder, washboard abs, a full chest. I like to be able to choose. It’s an internalized sense of inadequacy that determines how I basically don’t present myself on Jack’d.

Where do you think that—let’s call it—“aesthetic overload” comes from?

One of the gifts of being gay is the nonreproductive part. As a gay person, you get to be visceral and primal and utterly exposed to another person without the fear of pregnancy. It’s just a straight-up viscerality that’s available to us, to lesbians, and to all kinds of queer people. Again, we live in a society that is primarily consumerist. The subconscious way that people operate or function is through the idea of consumption. Get as much as you can as often as you can. It’s as if we’re wrought in a non-ethic of accumulation.

How does that relate to queerness?

I’m all for the reconfiguration of relationships and thinking about different ways in which people can be in relationships beyond monogamy. I’m totally here for that. Even if we have a politics that attempts to resist some of the capitalist tendencies that exist inside of monogamy and the traditional monogamous relationship by being differently formed, we can’t completely rid ourselves of that sensibility. It’s consumerist. It’s a desire for accumulation.

I would also call that being human.

The other part of it is, most of us don’t live in the kinds of isolated communities that we grew up in. There isn’t accountability to community in the same way. It’s almost like we lack a particular kind of groundedness that would inspire or bolster more genuine connection.

The sexual social revolution has changed how we define intimacy and fantasy online, whether that’s through OnlyFans, Sniffies, or subcommunities like Freak Twitter. What have we lost, and what have we gained as a result of that?

I don’t know what we’ve lost, because humanity’s always been debased. I came across a quote from Sigmund Freud today that said, “I have found little that is ‘good’ about human beings on the whole. In my experience most of them are trash.” Your question implies that there was something to lose. It implies that there was something pure and pristine that we lost, and I don’t think there was ever a period like that. Part of what we’ve gained, however, is an entry into kinds of fantasy that people may not have had as easy access to before, and that can be really powerful. Religion is nothing if not fantasy.

In what way?

Speaking from within the confines of my tradition, God comes into the world in the person of Jesus Christ. They execute a brilliant healing ministry. It inspires tons of people but threatens the state. So the state kills him. Then God is like, Ha! You thought you had me, I’m back.

Just like that Miley Cyrus meme.

It’s very much giving “They tried to kill your favorite bitch.” Jesus comes back and people are like, What the fuck?! To believe in Jesus is to believe in the spectacular and the miraculous. There is a certain impossibility and also a certain absence implied in Christian belief. That is fantasy.

True.

A religious discipline teaches you there’s always more than what you’re seeing. That’s not to say that these platforms, which provide access to various forms of fantasy, are not also caught in the consumerist culture. They are in no way innocent. They are in no way invulnerable to violence, to abuse, to perversion. Michel Foucault said, “Not everything is bad, but everything is dangerous.” There’s a sense in which these things that invite us into a more vast experience of reality and even perhaps ourselves are wrought with danger.

Certain people, especially today, are quick to equate difference with danger, not realizing there can be beauty in difference. Right Reverend Mariann Budde recently went viral for asking President Donald Trump to show mercy to LGBTQ+ and migrant communities. Given this fractured political moment, do you feel a sense of duty to speak up?

I do feel an obligation to resist in a public way, and developing a platform to do that at a very high level is something that I’m working on right now. It’s time for Christians of good conscience to enter the fight with an arsenal of criticality and beauty, and to present the gospel in a way that is honest to the gospel and not whitewashed by complete mania and absurdity. Mercy and love are fundamental Christian orthodoxy. But I am also not interested in constantly reacting to the gross stupidity of that person.

So that’s the work—mercy and love?

The priest is a mediator of Christ in the world and to be an example of God’s love. I don’t get to turn that off in romantic relationships. There’s a certain degree to which I approach everything in life as like, “It is my duty to love this” and “It is my duty to pursue love and to do it bravely.” So I date a lot. And it doesn’t work out a lot. But in a way that builds up the callus to continuously pursue love with grace. It is my love of God that informs my love of love in general.

What do you say to people who say your idea of love is wrong?

I don’t give a fuck.